Projecting the Future of Art and Education

Linked to Metronome is Future Academy, an international research initiative set up in 2003 that investigates the future of research and production through art colleges in Europe, West Africa, India, the USA, Australia, and more recently Japan. Having previously worked in over a dozen countries from Senegal to Scandinavia, Clémentine came to Tokyo in 2006 and spent over six months here, organising a think tank at the Mori Art Museum, and publishing a new issue of Metronome in collaboration with documenta 12 magazines and educationally oriented art organisations such as Arts Initiative Tokyo (AIT), commandN and co-lab. The result, which has just been presented at documenta 12 in Kassel, is the bilingual Japanese/English edition of Metronome No.11 ‘What is to be done? Tokyo’, with contributions from leading Japanese artists and curators.

How did you get into working as a curator?

I was born in London, but with a French mother and an Austrian father. When I was 17, I studied art in Vienna, where I was the only foreign art student. This is impossible to imagine in contemporary Europe: art academies are now 50% foreign. I realised at that time that art was about information, so I went to university and studied social anthropology, which was the most lateral of all disciplines at the time.

Coming from a European background rather than a British art establishment background, I saw curators rather like cyclists riding a tandem bicycle: they peddle alongside artists in order to develop new ideas, new modes of production and new ways of presenting work. However, this hands-on approach to being a curator was not the way things were done in Britain in the late 80s. Exhibition organisers would solicit academics who would propose the subject matter and then the exhibition organiser would set up the loans of works, organise the education program, etc. In contrast, in Switzerland, Germany, Austria where I had been educated in art practice, you found (mainly male) curators like Harald Szeeman or Kaspar Koenig who did not feel that they needed to be neutral or objective towards the artists they were working with.

That’s the background that I have: I’m not interested in being receding and supposedly objective in the way that I work with artists. Instead, Metronome allows me to short circuit art scenes through a much more subjective approach to curating.

What made you start Metronome?

I started making books as a curator in 1996. I felt there was a real need to do more international work that went a little bit deeper under the surface. I had worked in different parts of Africa with intellectuals and conceptual artists on new kinds of infrastructural projects seen as art practice (e.g. Laboratoire Agit’Art in Dakar), but it was complicated to show these new formats as finished works in the context of an exhibition.

I thought that it would be more useful to come back to the ‘organ’, a format that every now and again, writers, artists and activists of various kinds come back to because it allows them to say things when the press has become too standardised. I felt that most art magazines resembled one another, that exhibitions were becoming equally monotonal and similar and that if I set up an ‘organ’ maybe I could short-circuit the interests of one artist living in Lagos or Dakar with an artist living in Tokyo or Stockholm.

To do this, I shifted my focus as a curator from doing exhibitions defined by space and visitor numbers to working as a curator who interested in connecting artists to other artists through research and publishing.

How has the world of curation changed since you started making Metronome ten years ago?

Ten years ago, there were fewer biennales and curators didn’t travel so much. Over the last ten years, curators have come to rely on biennales, but that does not necessarily imply that they can work well or easily with other cultures.

I don’t believe in the possibility of very broad curatorial activity. If you want to do it like that you become more of a cultural manager, and I’m not sure that art is a cultural project at all. It becomes part of a culture industry, but initially it is more specialist. I think it’s more comparable to science and forms of research and therefore it’s not always going to be easily accessible.

Also, I think artists have become interested in refining the collective situations that they’ve become involved in. Many artists have got to know each other at biennales, but what kind of collective sensation is that? They go to whichever biennale, work together, get to know each other and all of a sudden, it all dissipates. The process of artistic exchange is structured around an event and that is phenomenally superficial. Through Metronome, I have produced more intimate relationships that operate on a conceptual level between artists who wouldn’t normally meet; I don’t need to rely on a big event structure with a lot of money in order to connect them.

While it is becoming easier for people to travel and move between biennales than it was ten or fifteen years ago, the majority of the world’s population does not travel in that way; such freedom of movement is still the preserve of a minority. How do you reconcile the apparent gulf between the global and ‘local’?

I think the ‘local’ is people. I cannot accept the idea that locality is based on land or territory or location. For me, I’m local to Tokyo because I’ve got to know certain people here. I’m not local if I’m a tourist or if I’m just passing through, but the moment I start to know people, form relationships, and shape my life around people here, then I’m local. That’s how I see the ‘local’ in the context of a moving, globalised world. I get unhappy when I sense that people are making a fuss, be it positive or negative, about a locality or a neighbourhood. It’s not about areas in terms of land: areas are only as good as the people you meet.

Do you feel that curating has become standardised?

There now seems to be very unified approach to curating and I don’t know why that is. For me, curating ultimately means that you enter into a work conversation with an artist, a serious one in which you give each other mutual feedback, and that you lead this conversation towards a form of production and then a form of dissemination. Nothing tells you that you have to produce an exhibition; nothing tells you that it has to last 100 days; nothing tells you that it has to have a catalogue. It can use several different media, beyond exhibitions. As a curator what you need to do is to recognise what it is that you’re interested in. It’s not so different from the kind of approach that a researcher would adopt.

What is it about book publishing that you find works as a medium for your curatorial ideas?

I think the art world operates with a very orthodox matrix in terms of professional definition. You can effectively count the roles that are available on two hands: artist, critic, curator, museum director, gallerist, art college director, collector, dealer. So not only is the definition of the roles narrow but within curating, there’s also the problem that people don’t work on the differences that exist within this area of production.

I work in publishing because each time I produce Metronome I able to do something that’s differentiated. When I come to a place I have to see and suss out whether I can do something there, I have to meet people, I have to feel something and then organically I start inviting people into this situation. At that point I may be visiting someone’s house, or in a library or just generally looking around, and I’ll come across something that I’ll identify as a reference for research and that becomes the vehicle for the generation of the new work. Once the process is reasonably developed and I can distinguish the otlines of the next Metronome, I try to find the funding, which is usually mixed national, and then I produce on site. Every single Metronome has been researched, designed, and printed in the place I lived. This form of curating as publishing is the final result of a much more interpersonal way of working.

How has that process worked in Tokyo? What did you find that was local here?

The first thing that I was particularly excited about was the phenomenon of artist organisations that are also interested in education. Education generally is not a terribly sexy arena for art production. However, when I came to Tokyo, I saw that there was the artist and designer-run space co-lab, AIT, and commandN with Masato Nakamura and his proliferation of smaller projects that had educational remits to them.

AIT were very interesting because of the flexibility of their office space and the fact and that they survive financially mainly off their evening classes. I wish more people did evening classes on curating in Europe: AIT is wonderfully informal as an educational structure and it actually provides an outlet for the teachers as well as the students.

I was impressed by the fact that Japan has artist-led organisations that are not afraid of education. As I’ve been working on Future Academy, I thought it would be good to become more involved here.

You have worked in dozens of countries, throughout Europe as well as the US and Africa, connecting with creative people with whom you can collaborate on Metronome. How did you connect with Tokyo?

I had been given initial contacts through an artist called Alan Johnston, who has been coming to Japan for twenty years and is part of the older generation’s network here. He was the one who told me to meet Roger McDonald from Arts Initiative Tokyo and I gave a talk there the first day I landed in Tokyo. Through AIT, I met artist Masato Nakamura and he offerend me a residency and a show of ten years of Metronome. At the same time, I met the director of the Mori Art Museum, Fumio Nanjo and that led to the two-day Metronome think tank being held at his museum.

Can you tell us more about how this think tank held at Mori Art Museum came about?

Having traveled all around the country, meeting artists in Osaka, Kyoto, Hiroshima, Yamaguchi and elsewhere, I came back to Tokyo and suggested to AIT that we organise a think-tank on the relationship between art and education. As Metronome is an official participant of documenta 12 magazines I was able to get them involved and the curators attended the think tank and supported it.

The concept was to bring in about 30 people I had met from Japan and 30 people I had worked with elsewhere in the world to Tokyo and moving on from the structural or architectural analyses of Future Academy, look at the question of future forms of knowledge, cultural translation, and art research in art colleges. In other words, we considered what kind of information seeps through artworks today that will lead us to define new epistemologies for the future. How many art histories do you need to teach today if your students are 50% foreign or non-nationals? You can’t just teach oil painting: we inherit these traditions and we try and transform them, but if you were to rethink the faculties of knowledge of the future, then what would you propose?

People attended from all over the world, and the Mori Art Museum agreed to host it. It was held behind closed doors as people speak differently in that situation. The edited transcription can be read now in Metronome No. 11.

It’s true that being behind closed doors facilitates discussion of a kind that will not take place in public, but equally you said earlier that art is not always about being an easily accessible set of media. The art world is often accused of being opaque and elite, and there is the increasing expectation that meetings of this kind should be made more transparent. What do you think?

I think it all comes down to differences in production. It’s interesting to look at it through a farming analogy: there are some farmers who breed chickens, some that grow wheat, others who outsource their industry; these are all these different ways of producing. There are some farmers that go all the way and use genetically modified products, work with the latest machinery and achieve huge levels of production and distribution that are even globalised and link up to farmers in other parts of the world. These formats of production are reflected in the cultural industries too, through museum exhibitions, collections, and biennales. At the same time you can have smaller modes of production that have the autonomy and authority to negotiate what they want to do.

Metronome is not easy to find. Artists know about it and it is becoming more and more well known but ultimately it’s about enabling production in a time when everything has to be a cultural product and has to be accessible. I’m not trying to be secretive because I think that’s particularly exciting, I just don’t want to compromise.

Can you tell us what happened at the Metronome think tank?

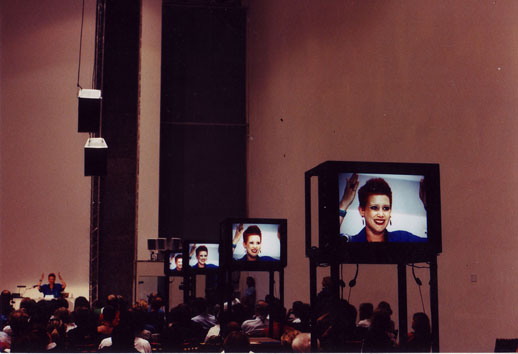

Each of the participants had ten minutes in which to present the heavy questions: What the core of their work is and what the problems are, but without speaking. Their ideas had to be communicated in essentially performative and visual language. It was fascinating and very powerful to spend the first two hours just watching things happen without anybody speaking as you’d normally find at a conference. Some compromised and talked using powerpoint, and some did crazy performances. In addition, everyone who came had to present between one and four images that were illustrations of future faculties of knowledge. In other sessions we debated key problems of mobility, translation, and knowledge as these relate to the future of art research and production in the framework of art colleges.

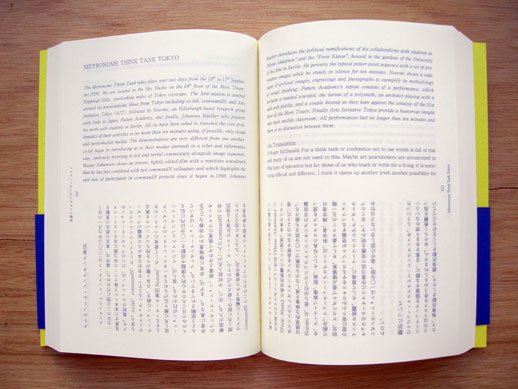

I transcribed and edited all that material and worked with Lena Oishi on the Japanese counterpart. As a result the book is fully bilingual. After my editorial and the table of contents, you have uninterrupted images of 130 future faculties of knowledge plus all the texts that participants wrote on faculties: US curator Stephanie Snyder and writer Mathew Stadler on the Faculty of Magical Thinking, Yuko Hasegawa on the Faculty of Surfing as a Physical and Metaphysical Practice, French curator Thomas Boutoux and sociologist Boris Gobille on the Faculty of Anonymity and Self-Subversion, and so on. Then you have 150 pages of the edited transcription of the Metronome think tank, shuffled where necessary so that it makes sense to the reader. After that you have a whole section of texts on questions of mobility and translation, written again by both Japanese and foreign artists, architects, scientists and curators. And then you have a document of some 25 pictures of the actual think tank as it took place in Tokyo.

I don’t know, maybe it is harder to know where to stop than to invent! Maybe because I started Metronome in the 1990s when there was an excessive over-designed graphic feeling to publishing and everything was overlaid with inserts and images? I’ve always liked clean graphics, 60s and 70s conceptual books or earlier, magazines from the 20s and 30s. Once the core of the research has been identified, I’ll take a local example of that form of earlier artists’ and writers’ organ as a model for the new issue of Metronome.

Which book did you choose for this issue?

Unusually for Metronome, this time it’s not an old book, but a very new one called Sleeping Beauty or Art and Education by Masato Nakamura. It’s a trilogy made over the last ten years that the artist regards as an artwork as opposed to a regular book: a series of interviews with artists on why they became artists and what they feel about education. Nakamura was happy for me to adopt his work as a reference. Metronome No.11 uses the same size, yellow cover, paper, and only the layout is slightly different because Metronome is bilingual and includes images. But I was also influenced by the 1940s Japanese propaganda magazine, Front. From Front I adopted the use of monochrome printing, and produced Metronome No.11 in indigo blue ink.

What’s your approach to distribution?

The dynamics of Metronome began when I produced two thousand copies in Dakar in 1996. I brought them back to London knowing that regular bookstores wouldn’t be right for distributing the book, so I distributed it through the artists who took part or I’d distribute it in the way that I gave you a set of copies just now. It’s only recently that I set up Metronome Press in Paris with Thomas Boutoux, and we have added barcodes and ISBNs to some of the books that we have produced.

Do you think you will come back to Tokyo?

I believe that desire and friendships are the basis for good artistic collaborations so I’m very loyal and I will go back the places I have lived and worked in. If you look at the Metronome Press website, you will see that certain contributors have been involved in four or five Metronomes already. I’m not interested in always looking for the new thing in a new place, and therefore when I go somewhere, as with the Tokyo edition, it doesn’t just involve Japanese people, it involves people I have worked with previously. Wherever I do the next one, maybe artists and writers from Japan will be part of it. I have to make sure that the connections survive, and they don’t survive easily in this world.

Ashley Rawlings

Ashley Rawlings