Smith forged knives, Tosa blades: Fujigen Hamono Seisakujo

There’s a very manly line of knives being produced in Kami City, Kochi prefecture under the name of Hokubo. Behind these knives are four hundred years of local bladesmithing expertise. Tosa, the old name for Kochi, is a name practically synonymous with good blades, and the area is one of the five major blade-producing regions in Japan. We visited Kochi and spoke to one of the talented craftsmen behind these rugged-looking blades, Satoshi Yamashita of Fujigen Hamono Seisakujo.

Q: Mr. Yamashita, you’ve just joined JAPAN BRAND as a manufacturer, isn’t that right?

A:Yes. I’m very grateful to have this chance to try something new despite my advanced age. I want to do my best. But to tell you the truth, I’m feeling pretty worn-out these days. (laughs) Right now, the Kami City Chamber of Commerce and Industry is working on plans for the third and forth items in the series. I can’t tell you the exact details, but our product development project is going to start taking shape soon.

Q: All the products you’ve made so far for the JAPAN BRAND project have quite a wild image, and I’m sure most people would think they’re really cool.

A: Speaking broadly, Tosa blades traditionally include kitchen knives, but blades used in farming and forestry are the main products, and Tosa blades hold fifty percent of the domestic share for blades used in forestry. That’s why you could say it’s the blade that has been tempered outdoors.

Q: Why was a kitchen knife chosen as the product to develop for the JAPAN BRAND project?

A: Tosa blades have a history that goes back to the Edo period. The greatest thing about our knives, which are said to have four hundred years of tradition behind them, are the free forging techniques we use to make them. We eventually have our sights set on markets overseas, but for now we want to get our product into the domestic market here in Japan, and we decided the kitchen knife genre would be best suited for that.

Q: I see. And now you have settled on “Hokubo” for your brand name and the second item in the product series has already been developed, isn’t that right?

A: The first item in the series is called “Katsuo” and it’s a cooking set for making the local specialty, katsuo tataki. The second item is called “Oatsurae” and it’s a made-to-order knife series. That product features a double-edged blade which means it stays sharp longer, and the handle is made with a lacquered finish. The look of the knife shows how it has been smith forged with the tell-tale black finish and the demarcation line that shows where it has been sharpened. We have been focusing particularly on making blades with the black finish, which could have led to the wild impression you got from our products. As I said earlier, we’re currently working on plans for the third and fourth items in the series.

Q: Now, what kind of blades do you generally make at your forge, Mr. Yamashita?

A: My family has been running a sickle forge since my father’s generation. We’ve always made sickles for farming and forestry. Though they’re all called sickles, there are actually quite a lot of different tools that fall into that category. Some are for cutting grass; others are for trimming branches, and so on.

Q: In that case, most of your customers must be farmers who need those tools for cutting grass and things like that.

A: Yes, mostly. But, farming is getting increasingly mechanized, and people use mowers for that kind of work instead of cutting the grass a handful at a time. With this change in the times, the number of blades we make has also fallen quite a lot. We only make about thirty per day now.

Q: Is that right. So, what kind of people come looking for sickles in this day and age?

A: Some people have been our customers for years, and a lot of our customers are quite particular about their sickles. The sickles we make are nothing like those blades made in China that sell for a couple hundred yen. We go through a long series of processes to manufacture ours, so they’re certainly not cheap. People who look for the value that comes with a product made with so much personal care are the people who come to us. We have farmers and regular people who come and buy from us directly, and we also sell wholesale to forestry cooperatives, farming cooperatives, and hardware stores.

Q: How many steps would you say there are in making a sickle?

A: There are five major processes involved., Smith forging, rough finishing, tempering, annealing, and then blade grinding.

Q: What is the most difficult process out of those five?

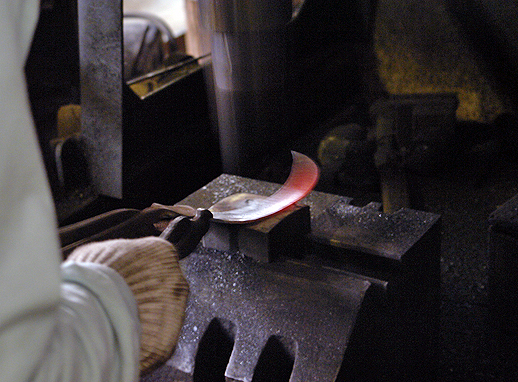

A: That would be the smith forging, I suppose. To form the base metal, we build a very hot bed of coals from pine charcoal, and heat iron until it is red-hot, about a thousand degrees. Then we strike it to form it into shape. Next, there are a couple other steps involved in creating Tosa blades. They’re called warikomi and wakashi. This is where we fold steel into the iron. This helps to make a sharper blade, but it’s a very advanced, very difficult technique.

Q: I understand that many forges these days use steel presses to eliminate some of the steps involved, but you’re still doing everything the old fashioned way, over a charcoal fire. Why is that?

A: I think the customers who come to me for the sickles I make are the biggest reason. The cutting edge and ease of use are the most important. If I slack off and the blade winds up being thicker and the cutting edge isn’t as good, my customers will say, “Hey, this doesn’t cut very well!” and they’ll leave me. But we’ve got a declining forestry industry, increased mechanization, and cheap imports. This is truly a dying industry. I figure the least I can do is make a good product.

Q: When was the peak of the sickle smithing industry?

A: It seems my father made his best money from the end of World War 2 until around the 1960s. But by the time I came into the business, it was already headed downhill. (laughs) I’ve never really experienced an era where business was going well.

Q: Mr. Yamashita, did you become a blacksmith because you were the eldest son?

A: No. Actually, I’m the youngest. I had always watched my father at work since I was a young boy, and got him to let me help out. So I always knew basically what kind of work was involved, but I never really felt like taking over the shop. (laughs) But it just so happened that I wound up taking it over after all.

Q: Did your father teach you when you learned how to make everything?

A: I’d always watched when I was a kid so I had a good idea of what to do, but yes, he taught me the fine points of the work. I’m not sure I could really call it teaching though. My father was the type of guy who would lose his temper if he tried to teach something to somebody. So he never said, “do this, do that” with words. He said he figured, “if you’ve never done it before, you won’t understand even if I tell you.” So instead of talking, he would just do it and I’d watch. I’d stare at my father’s moving hands and learn, that’s how you form that angle, that’s how you get it to curve the way you want, and then I’d mimic what I saw.

Q: How long did it take you to master everything?

A: They say it generally takes at least five years. But I’d already been surrounded by it since I was a child, so I figured I’d be able to get to the point where I could make a commercially viable product in about two years. I had just left my company job and I had half a year’s worth of unemployment insurance coming to me, so I was planning on just going along at my own pace. But when I got into the workshop and started out, it was much harder than I had imagined. Plus, I found out I’d only be able to collect unemployment for three months. So I really had to get serious. I managed to learn enough to be able to make something saleable after a year, and I’ve been eking out a living ever since.

Q: I see. It’s amazing what a man can do when he’s cornered, isn’t it. Lastly, please tell me about your plans for the future.

A: In my case, my two daughters have already married out of the family, and I don’t have any sons to take over the business, so I’m planning on being the last one at my workshop. Mind you I’ve still got this JAPAN BRAND work to do, so I think if I can make something new with all the forging techniques I know, that would make me happy. I’d just like to enjoy myself as I work.

Fujigen Hamono Seisakusho

Shingai 184, Tosayamada-cho, Kami City, Kochi

A Word from a Regional Project Participant

Management Facilitator, JAPAN BRAND Project

Kami City Chamber of Commerce and Industry

We started participating in the JAPAN BRAND project in 2006. During the first year, we conducted a study to decide what direction to take, and as a result we are working on getting our name recognized on the domestic market. Tosa blades have a long tradition, and the hand forging techniques used are truly amazing, highly refined skills. We decided that the best way to let people know about what we’ve got is to develop a line of kitchen knives, and started our Hokubo brand. There are three manufacturers and three wholesalers, for a total of six companies participating in this project.

For the first stage in the project, we enlisted some outside help with developing “Katsuo.” Katsuo tataki is a local specialty where a thick fillet of katsuo fish (bonito) is laid over the tines of a pitchfork-like tool and seared over an open flame. Tanaka Sengyo-ten, a famous local producer of this delicacy, supervised the tool development. The handle was finished with Wajima lacquer by Kirimoto Mokkojo, and we asked Hiroshi Innami, a designer and professor at Shiga University who was born in Kochi, to supervise the design.

The second stage builds on the product we made in the first stage. We offer several types of handles and blades so that the customer can make his or her own original kitchen knife.

On the sales side of things, knives as a product genre can be difficult to market due to their evil image (ie. being used in committing crimes). However, despite this, we believe that if we target middle and older aged men who are interested in cooking and put a concerted effort into promotions, we’ll be able to evade that issue. We’re currently working on a new product lineup that will help energize the local community. The JAPAN BRAND project opens up chances to do promotions, hold business negotiations, and find trade channels that a single company would never be able to do on its own. I hope we can use this opportunity to its fullest.

Japan Brand

Japan Brand