Cherry Trees on My Mind

Kozo Miyoshi

Talking to Kozo Miyoshi, one of the veterans of postwar photography in Japan, is like being constantly reminded of an old — one would say classic — almost ascetic approach to photography. During his forty-plus years of activity, Miyoshi has progressively slowed down, consciously deciding to favor quality and purity of expression over quantity in order to capture on film only what he truly finds worth of his attention.

How was the Sakura project originally born?

In 1998 I left my house in Yoyogi, Tokyo and followed the “cherry blossom front” through Nagano, Fukushima, and Yamagata prefectures up to Hirosaki in Aomori prefecture. Since then, every spring I repeat the same journey to meet “my cherry trees.” For me it’s like a journey of discovery: Every year I get to meet new friends, and then of course there are my old friends who are waiting for me. Come the end of March, everybody knows I’m gone on my trip and it would be useless to look for me at home.

Your approach to photography usually takes you away from the city, right?

Yes, I’ve lived in big cities such as New York and San Francisco, and my Japanese residence is in Tokyo, but in order to pursue my art I always head out to the countryside. It’s the same wherever I find myself.

Are you always going alone?

Yes, I’m not really good at team work or collaboration. I’ve only done collaborative work once or twice, but I find most satisfaction in working solo. Photography for me is a solitary activity. I like to work slowly, sometimes undertaking three to four projects at the same time. Completing one series it usually takes two to three years, sometimes even four to five years, which works just fine for me.

I take pictures first and foremost for myself. When I was still a student I worked on a couple of assignments on a part-time basis. At the time I knew nothing about original prints, photo exhibitions and selling my work, but then one day I saw a documentary film on Edward Weston. That was the first time I really learned about someone who had chosen photography — especially art photography — as both a job as a way of life. I immediately thought, “This man is way cool!” I was so in awe, in 1972 I crossed the Pacific and spent one year in America.

Back to our subject, why did you choose cherry trees?

My choice was a little strange indeed because most people are attracted by the blossoms’ colors. I, on the contrary, have no interest in colorful things. They don’t move me to take pictures. Even when I look at cherry blossoms, I don’t see colors; I can only see different shades of gray — especially those very pale grays which are closer to the color white. This is the kind of effect I try to achieve with my photography.

Is that why almost all your photography is in black and white?

Yes, only a couple of my series are in color. Really, I almost have no interest in expressing myself through color. I’m not after the decorative effect, but the trees themselves. My work consists in translating these forms into a play of light and shadow through the black and white photography.

Another element that makes your photography so distinctive is the size of your works. Is there any relationship between the subjects you photograph and the way you capture them on film?

Not really. Actually you can find a stronger connection with my modus operandi. You see, in the beginning I used 35 mm film. The “problem” with that is, you always end up taking too many pictures, and then you have to sift through them and choose what you really like. I find this process utterly empty and futile. For me the selection should be made before actually taking a picture. That’s why, in order to achieve this result, I’ve progressively used bigger and bigger cameras, especially the 8 x 10 — that I started using in 1982 — and the 16 x 20 that I mainly use now. The actual task of hauling around and setting up such big heavy cameras is such that you don’t want to repeat the same operation again and again. In a sense it’s been like developing a kind of personal discipline; being strict with myself regarding the very act of picture-taking. I find satisfaction in this simplicity; in stripping photography to its basic elements.

You never work with digital cameras. Don’t you like digital photography?

On the contrary, I find digital cameras very useful. It is true that when it comes to creating a work of art I express myself better through gelatin prints, but digital cameras have their place in my work, especially as means to gather and order data and information.

I understand very well that young people prefer and sometimes only know the digital medium. That’s fine with me, and I believe the two approaches can coexist. It’s just that we run the risk of forgetting our great photographic tradition. In this sense older people like me have a duty to keep the older techniques alive.

Asako Narahashi

Asako Narahashi shoots what she wants, when she wants, without being too self-conscious. Originally an accidental photographer, she has pursued her passion for the last thirty years without thinking too much about making it a career. She is just content with “sleepwalking” through the world, making up her own reality.

In your work you often seem to mix dream and reality. What do you think about this?

I myself don’t really like to use the word ‘dream’ when I refer to my work. I consider myself a pretty realistic person and I’m not really interested in the world of illusion. Maybe it’s a parallel world. For the same reason my work is more about ‘taking’ than ‘making’.

I mean the ‘post-production’ work many people now do by manipulating images with a computer. You will find nothing like that in my pictures. I’m often asked if my photos are somewhat computer-altered, but I only take pictures of things that get my attention, the way they are, and that’s that.

Do you do everything yourself from start to finish?

I only get the film developed by a laboratory because it involves the use of chemicals. After that, I do the printing myself unless the size is too big. Especially when I show my work abroad, they ask for bigger prints, something like 90 x 120cm, in which case I have to get the photos printed somewhere else.

Does this approach extend to the stage of conception?

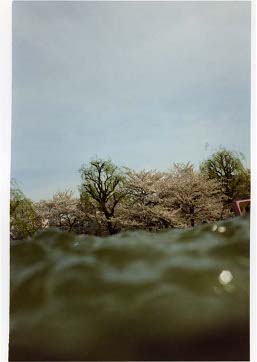

Yes. Actually there is little theorizing behind my work. Take, for instance, the “Half Awake Half Asleep in the Water” ongoing series featuring one of the photos on display in this exhibition. I was on vacation at a place by the sea and I happened to have a waterproof camera with me. I was just floating in the water like a sea otter, taking pictures with my camera half submerged. I liked the results but I did nothing with them for about one year. Only later I had another look at those photos and suddenly I was struck by something and began to regard them in a different light. That was when the series really got going.

So in a sense you first shoot and only after you think about the significance of what you have done?

Exactly, it’s as simple as that. It’s not a very conscious approach. On the contrary, chance plays a big part in what I do and the results I get. Under the right circumstances (which are also something I don’t decide beforehand) any place and any subject can be good for shooting pictures. I’m fairly open to any kind of external influence. In a sense I entrust the camera with taking pictures for me, like when I shoot in the water without actually looking in the viewfinder.

These shooting sessions in the water can be rather tiring, I think. How many pictures do you usually take in one session?

I generally use between five and ten 36-pictures rolls of film. I spend quite a lot of time in the water, and sometimes I end up drawing people’s attention. I remember once, I was staying at this little resort hotel, and when they saw me floating in the water they thought I wanted to commit suicide. It was pretty embarrassing (laughs).

Your series have such titles as “Half Awake Half Asleep in the Water” and “Coming Closer and Getting Further Away.” One can feel a sense of uncertainty, of been caught between places. Do these titles refer to yourself and your position in the world?

No, not really. Regarding the pictures I take in the water it’s a more direct reference to floating and being carried by the waves, by turns getting close to the coast and then been carried away. Although more in general you can see it as a comment on my somewhat careless approach to photography; this taking pictures without any deep thought, always shifting my stance and been slightly off center. You could say I like to surprise myself. If things are too well thought-out before I even start shooting, it quickly gets boring.

People who have seen your three series (the two mentioned above and “NU-E”) often say that they look as if they were the work of three different people.

Yes it’s true, I’m often told that myself. I guess this is because people can only see the finished projects. Of course each series has a definite character that is different from the others. What people don’t know, though, is that the three projects kind of overlap each other. I’m always taking pictures, without a clear idea in my mind. Only later I sit back, look at what I shot and start seeing a theme taking shape. I never think, okay, this project is over, now let’s start a new one. Things are never so clear-cut, at least for me.

Recently Japanese photography seems to be very popular worldwide, after many years of being overlooked abroad.

Yes, it’s been a long journey, like mine. Even me, for twenty years I couldn’t make a living through photography and had to work other jobs in order to support my passion. This is quite common in Japan. Abroad, I think many people decide at a pretty early age whether they want to or can pursue this career professionally. In Japan, though, many people keep shooting just for the love of it, without really being concerned about money or having a career. This, in a sense, has been a blessing in disguise for Japanese photography. Of course there is also a negative side to it: Abroad it is normal to see photography as an art. Many people go to photo galleries and actually buy pictures. In Japan unfortunately it’s not so easy. Maybe it’s because the habit of taking pictures is so pervasive, instead of purchasing an artist’s work, many people prefer to hang their own photos in their house.

“Cherry Blossoms of Memory” runs March 23 to April 10 at RICOH Photo Gallery RING CUBE in Ginza.

For more information see:

http://www.ricoh.com/r_dc/ringcube/

Randy Swank

Randy Swank