FILMeX: Platform for Japanese arthouse cinema

Now in its twelfth year, Tokyo FILMeX has firmly established itself as an important venue both for introducing new Asian filmmakers to Japanese audiences, as well as for significant retrospectives of Japanese cinema. Co-creator of FILMeX and producer at Office Kitano, Shozo Ichiyama knows a thing or two about contemporary film. TAB catches up with him for an in-depth talk about Tokyo film festivals, independent cinema, and the past and future of arthouse theaters in Japan.

Could you describe the background of FILMeX? How did the festival begin?

Ichiyama: We started Tokyo FILMeX in the year 2000. At that time, many people in the Japanese film industry were worried about the situation of arthouse theaters. During the Eighties, there had been many arthouse theaters (“mini theaters”) in Japan, and there were good audiences for artistic films. The Hibiya Chanter, for example, opened in the Eighties — in fact, it’s still open — and a film like Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire could play there, and it was a big hit. Some of these theaters were very successful.

By the middle of the Nineties, though, we felt that it wasn’t so easy for arthouse films to have such a success. Some very good arthouse films were not being released in Japan at that time. Even if we saw such films at festivals, often they were not being released in theaters afterwards. So, we felt that there should be a festival which focuses on the arthouse cinemas. I had been working in the Tokyo Film Festival (TIFF) from 1992 to 1999, and of course they show some very good arthouse films but they also show commercial films which will be released in Japan very soon. Even if TIFF is showing good arthouse films, many people don’t realize it because their attention is going to the commercial films.

Of course, it’s very difficult to define which films are arthouse and which are commercial. Actually, we didn’t care so much about this distinction between “arthouse” and “commercial”, but we felt there should be smaller festivals with a very limited number of films, all of which are very good and all of which can be seen by the audience.

In Tokyo FILMeX, for example, we show only ten films in the competition and ten in the special screenings. We also have retrospectives, but overall it’s not so much. Distributors and press, also, have a chance to see all of the films. If we consider film festivals around the world, of course not all are like Cannes or Berlin. In France, for example, there is the Three Continents Festival in Nantes, a small festival focusing on Asian, African, or Latin American films. In each country, then, there have been alternative film festivals. We felt a similar need in Japan, and so we started Tokyo FILMeX.

For this year, FILMeX has the competition program, special screenings, three different retrospective programs, and the Talent Campus. Could you say a little bit about the changes in the organization of the festival this year?

Overall, our framing of the programs has not really changed since the beginning. We have two main sections: the competition, which is focused on new currents of Asian cinema, and special screenings, which shows masters of Asian cinema and also non-Asian films. Also, we have retrospectives every year of Japanese and sometimes foreign films. This is the main framework. Last year we started the Next Masters program, and this year we changed its name to “Talent Campus Tokyo”.

We started this Talent Campus because we feel that film festivals should do more for the future of Asian cinemas. The Berlin festival has a Talent Campus and Busan has the Asian Film Academy, which provide workshops for young talents. We had wanted to do this for some time but lacked budget. Then, two years ago, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government came to us with a plan for workshops related to festivals, and they were looking for partners. Of course we were very happy to do this, and so last year we started “Next Masters”, inviting twenty young filmmakers, organizing lectures and so forth. This year, we have an official partnership with the Berlin festival, which is why we changed the name. Otherwise, the event itself is almost the same.

How does this partnership work?

I think it works very well. Actually, it is not a great obligation. We can do as we like, but we can consult Berlin about lectures or problems, and also representatives from the Tokyo Talent Campus may be invited to Berlin next year.

A big question that many people are wondering about concerns 3/11. What have the effects of the disaster been on film festivals and the industry? How has it impacted the amount of production in Japan, quality, or the types of works being produced?

There hasn’t been a great economic effect on the festivals this year, because when the disaster happened almost all of the funding was already confirmed. This year, we can do the FILMeX festival with the same range as last year. We are not sure about next year, though I hope we can have the same funding.

For the film industry, the biggest problem has been finding budget. Actually, even before the disaster, with the financial problems, the Lehman Shock and such, it was already difficult. After the disaster, the situation has become worse. Many projects have been halted or cancelled because investors do not want to go forward at this time.

Usually, we have considered that low budget films in Japan were around one million USD, but now many filmmakers are working on budgets of one-half million or less — around 50 million yen. Even then, it’s not so easy to find budget. I don’t know about next year, but for now filmmakers are trying to make films on very little — 100,000 USD, for example.

These are the numbers for independent films. How about studio productions?

For studio productions, it’s another story. People are still going to cinemas, but the successful films have been happy films or comedies, because audiences don’t want to see serious films at this time. Recent films like Hitoshi One’s Moteki or Koki Mitani’s latest film, A Ghost of a Chance — these films, I’m sure, will be successful. So, studios can make films but the subjects are more limited for now.

On the subject of funding, how about FILMeX? Where does the funding come from, exactly?

Most of it is public funding. The major funding source is the Japan Arts Fund, which is part of the Agency of Cultural Affairs [Bunkacho], and it’s almost one-third of the total budget. Another big funder is the Japan Keirin Association, which hosts a bicycle race and donates the proceeds to cultural events. TIFF also receives a lot of funding from Keirin. It may be private but it is controlled by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), so it’s almost a public fund. A remaining third comes from admissions and private sponsors.

Didn’t FILMeX previously receive funding from the Japan Foundation?

Yes, but it was not a lot. Their support for all festivals stopped after 2009, due to their own lack of funding. Maybe they are spending the money on other cultural events, but not film festivals.

As you know, the Busan Film Festival in South Korea receives 75% of its funding from the state, and it is now the most important film market in Asia. In Japan, do you think the current policies are working for the film industry?

No, in this situation it is very difficult.

Do you think a business case could be made that the government could provide more support and it would be good for the Japanese film industry?

The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry is funding film festivals for this reason, but they seem to feel it’s not useful for the film industry. Maybe that’s why they have started to reduce the budget.

I want to ask about your retrospective programs. In past years, FILMeX has held retrospectives of Japanese directors like Kihachi Okamoto, Satsuo Yamamoto, and Koreyoshi Kurahara. This year, FILMeX has retrospectives of Yuzo Kawashima, Shinji Somai, and Nicholas Ray. How are these programs organized?

Before, we had a partnership with the National Film Center (NFC). They created new prints with subtitles, we showed them, and then introduced them to other festivals, like Berlin, for example. This worked very well, but it finished in 2008 with the retrospective of Kurahara. After that, the NFC said they could not continue the following year, for budgetary reasons.

The next year, we had a small retrospective of Yasujiro Shimazu. We got money from the Commemorative Organization of the Osaka Expo. It was held in 1970, and they still have a small fund. The money wasn’t enough for twelve films, but we made three new prints with English subtitles.

After that, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government people came to see us about the Talent Campus program, and we also asked them about budget for retrospectives. They were very happy to assist with this, and so last year we had a retrospective of Minoru Shibuya. The program traveled to Berlin, Hong Kong, and other film festivals. This year, we will do a retrospective of Yuzo Kawashima.

Could I ask the cost of striking a new print with subtitles?

It depends. If we just strike a new print from 35mm negatives, it’s not so expensive, about one million yen. But if we need to create the film from a 16mm positive, it’s much more expensive.

This is because it’s an internegative process?

That’s right. The problem in Japan — and this is a big problem for us — is that many of the classic films are only stored as 16mm positives. It’s very strange, but maybe in the Sixties or Seventies, the studios destroyed some of the original 35mm negatives. I’m not sure, but what I’ve heard is that it was very expensive to keep the negatives, because warehouse space was limited.

If they have a 16mm positive, it’s possible for the major studios to show the film on television or DVD, but they’re not really interested in showing the classic films in cinemas.

I’d like to ask you some questions about the Japanese film industry. As the director of a festival like FILMeX, you have a unique vantage point on this. Which part of the industry do you think is producing especially interesting films over the past few years?

Sometimes the TV stations are actually involved in the development of interesting films, especially the satellite channel WOWOW. Over the past few years, their business has changed, but they are still involved in films and also TV works by film directors. Next year, for example, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s new TV feature will be shown on WOWOW. It’s five hours in five episodes. This is very good, and probably the big studios cannot create such interesting films.

So, sometimes TV stations can do this, but most of the big ones are only interested in commercial content. The satellite stations are different, though in both cases they are not interested in showing these films in cinemas, only on their channels.

What about the new lower-budget independent films that have received a lot of attention? I’m thinking of recent works by directors like Tetsuaki Matsue and Yu Irie.

Yes, they are able to make films for a very low budget. Shion Sono is also this kind of filmmaker. He is able to continue because he can make films on a very low budget — most are under one-half million USD. Even if they look like films with a one million dollar budget, the real budget is usually half of that. The films of Matsue and Irie are probably around the same budget, so I believe they can continue filmmaking.

What do you think about the possibility of exporting these very low-budget films?

It’s not easy. Shion Sono’s case is very special, because his films deal with some very violent or sexual matters, which can be easily exported. Or, the filmmaker Noboru Iguchi, whose new film Denjin Zaborger: The Movie [Denjin Zaboga: gekijo-ban] is now in cinemas. He already has cult fans abroad, and he can also make films for a very low budget. So, these types of films are basically genre films, and are therefore very easy to export, but perhaps if such films are just dramas then it’s not so easy.

Along these lines, I’d like to ask you about distribution. What is the relationship with distributors, and how does the film market operate at FILMeX?

Recently, it works very well because some of the films showing at Tokyo FILMeX had a big success in the commercial cinema. Like Shion Sono’s Cold Fish, which was shown at FILMeX last year, then released in cinemas at the beginning of this year. It had a very good success. Sometimes we ask the distributors to show their films and sometimes they come to us. Of course, it depends — sometimes we accept, but sometimes we cannot. This year, for example, we’ll screen Ryuichi Hiroki’s new film RIVER, which will be released next March. This is very good timing. So, recently we have very good relationships with the small distribution companies.

Over the past few years, do you see changes or new trends in the way that Japanese filmmakers are getting their films to the market, and getting them distributed internationally?

In general, it’s not easy to distribute Asian art films. If it’s a genre film, maybe the DVD companies will quickly buy it. This is how some of the Hong Kong action films get distributed, or a film like Cheol-Soo Jang’s Bedeviled, which we showed last year. This will be released on DVD. For genre films it’s possible, but for artistic films it’s more difficult recently.

Some of the Asian films which are for older audiences are easier to distribute, because most of the audiences for mini theaters are getting older. They are over forty years old, or sometimes over sixty. Some of the Chinese films which have very old-fashioned story lines may also work in arthouse cinemas, but for the films which deal with young people in Asia, it’s very difficult.

At the same time, the festivals like FILMeX, Busan, and TIFF all have programs dedicated to new Asian directors and of course the largest emerging middle class in the world is now in Asia. There seems also to be an emerging regional identity in Asian cinema. Don’t you see this as an potential opportunity for young directors?

Yes. That is the main reason we consider new currents in Asian cinema for the FILMeX competition. Busan, also, has a competition section for new currents that is open to young Asian filmmakers.

Festivals like Edinburgh, Sundance and Tribeca have been screening some films online, over the Internet. What do you think about this approach to reaching audiences?

Yes, we must think about this in the near future. In one way it’s rather scary for us because it might mean that we lose some audiences. At moment, there are people who come to FILMeX from Osaka, other cities, or from towns in the countryside. If we started to show films online, we might lose some of them. On the other hand, we would have new audiences who feel this is a good festival and they could participate. There are many people all over Japan who might want to attend FILMeX but cannot, so maybe we can find new audiences.

Since around 2006, the number of Japanese films being released in Japan exceeds that of foreign productions. This is a significant change, as it had been the opposite for the previous two decades. Overall, the total number of films released a new peak in 2008, with 806 films released in one year. This suggests increasing interest in cinema, the numbers are up, and yet at the same time we hear that the situation in the industry is difficult. How should we understand this?

People in the industry have felt that the situation is increasingly difficult over the past two or three years. Probably, the number of Japanese films produced has been reduced since 2008. The overall numbers may look higher because these include very small, low-budget films that are released on video or only show in cinemas as a late show screening or something, films which cannot really have commercial success.

Many people now are trying to make films by themselves, and there are many theaters looking for films. I think there may be too many theaters in Japan now. But they will show small, independent films even if there is almost no audience or commercial potential, and filmmakers can also pay money for the cinemas to keep the screens. So probably the overall numbers are because of the many small films, or those produced by DVD companies. The latter don’t expect any revenue from theaters. They show the film in a theater for one week or something, before they release it on DVD.

For the foreign films released in Japan, the distributor must pay some minimal guarantees, which means that they only release films that have some commercial potential.

As these numbers have gone up, do you see changes reflected in the audience at FILMeX? Has it increased? Do you see any demographic changes in terms of the age or gender of people attending the festival?

Yes, it has increased. Also, in the early years, the audience was older, while in recent years we find many more young people in the audience. Maybe they are students, or from universities.

One reason may be that some filmmakers who are over forty years old have become university professors, and sometimes they force their students to attend festivals. Many young people in Japan are now studying at the university, and studying films. I don’t know if they will keep seeing these types of films, but in the past few years at least, we are finding this new audience at Tokyo FILMeX.

Do you feel there is more interest in film culture in universities?

Yes, I think so. Actually, in the past two years some entire university classes came to FILMeX.

What about young audiences and the exhibition of independent films? You mentioned that a decade ago, when FILMeX began, mini theaters were having difficulties. Recently, again, we hear of this. How do you see the role of FILMeX in relation to mini theaters today?

This is a very complicated question, but one thing we must do is take part in educating audiences. If we didn’t do anything, perhaps young people would just go more often to multiplex theaters for commercial films and begin to forget that the arthouse films and theaters exist. We must think about the significance of artistic films, and to invite young people, and help create audiences for the mini theaters. I’m not sure how to measure this, but we must do it.

Another significant element in the creation of audiences is film criticism, whether it’s in journals, magazines, or published as academic research. What about the situation of film criticism?

It’s getting worse and worse, I think. We cannot readily find magazines that contain good criticism. On the other hand, we can find good websites which publish interesting criticism. I feel there are many young people who can write good criticism, but they cannot find magazines or newspapers to publish it. Maybe they can only write for websites, and they cannot get paid for this. Or, if they do, it’s very difficult to receive good fees for this criticism. They can volunteer, and some websites provide a place for them to write good criticism, but they must get money from other sources.

Maybe there are some changes in Kinema Junpo. Recently, I see the writers names are all changing and it seems they are perhaps inviting new critics or changing in some other way.

Do you see any possible changes in universities or government policy that could address this situation or promote criticism?

The Japanese government is only interested in the film industry. They do not pay any attention to film criticism. That is also why universities in Japan may have divisions for film production but they have none for criticism. It’s very strange, because for example in the Beijing Film Academy there is a department for film criticism. Some of their graduates have become professors and are writing good criticism. In Japan, I don’t think there is a university that is considering this and the government is not interested in such things.

The government doesn’t pay any attention to this situation, and so it’s difficult. Many of the rights holders are very tough and publications are not allowed to use their images. Most of the major studios don’t view criticism as any kind of promotion.

Finally, since FILMeX is now over ten years old, when you look back, what do you feel was the festival’s biggest mistake or missed opportunity, and its greatest achievement?

I don’t know if there have been any really big mistakes, or at least we haven’t noticed them. Sometimes we feel sorry that we cannot do complete retrospectives. Every year, of course, our budgets are limited. Like with the Yuzo Kawashima retrospective this year. If we had a very big budget, maybe we could have a complete retrospective of Kawashima, but we must concentrate on only a few films. Every year we have some project that we feel we could do more fully, but budget is an issue.

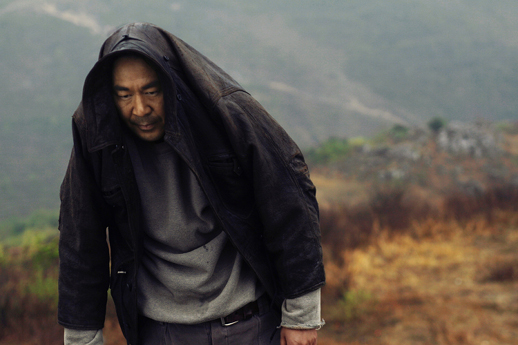

One of the biggest successes has been that some of the filmmakers that we screened in the early editions of FILMeX have become very good filmmakers now. In the first year, for example, Lou Ye’s film won the grand prize. He became one of the important filmmakers in China. We showed the first film by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and he became the winner of the Palme d’Or at Cannes. Also, we showed Zhang-ke Jia’s film Platform, and he later won the Golden Lion in Venice. Sometimes we find that we were right, that these filmmakers became big names a number of years later. This has been one of the most successful points.

FILMeX 2011 runs November 19 to 27.

M. Downing Roberts

M. Downing Roberts