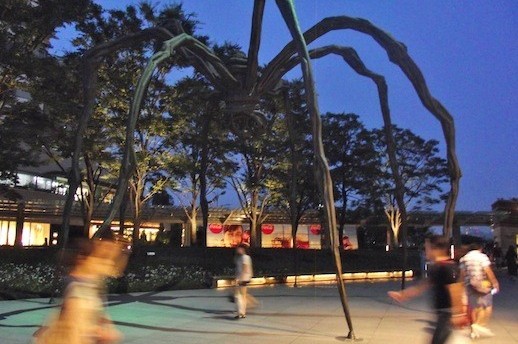

Public Art #3: Louise Bourgeois’ Maman

On an elevated plaza at the shopping and leisure complex Roppongi Hills stands Maman (2002). Made by the late French-American artist Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010), it’s situated at the end of a number of trellised walkways that all seem to lead to the iconic sculpture. Standing at about ten metres tall, the opportunity to go beneath it and gaze upward like a child is there for everyone.

In Tokyo, where structural regulations are so strict, it appears precariously poised. With its graphite tones deflecting its glitzy surroundings, your eyes follow the spindly legs up to a turbaned metal body before resting at the final focal point; the marble eggs cradled inside the mother’s sac. And whilst the weight of the eggs may not actually counterbalance the rest of the structure, they do so metaphorically. It may seem an unlikely metaphor, but this piece of public art honours motherhood, an ode to being and needing a mother: this is mummy, or maman in French.

Originally commissioned for Tate Modern, London in 1999, its first incarnation was on the bridge of the Turbine Hall. Within a renovated power station, its original backdrop was an industrial, cathedral-like space. The version in Roppongi, one of an edition of six bronze casts, is instantly recognisable as a female spider but even beyond the connotations of the machine age inherent at Tate, it retains an odd quality here; of being both organic and industrial at once, as though it could be made from grape stalks or barbed wire, a bound and woven structure, protecting its offspring.

It’s not an obvious ode to maternity. It could even seem more like a naked umbrella than a symbol of protection, much less so of nurture, but to appreciate Bourgeois’ oeuvre is to delve into the personal symbolism and biographical episodes that inform her work. Her own mother was a tapestry restorer who died when Bourgeois was twenty-one. Deeply traumatised her mother’s abandonment and despairing at her father’s despondency, she threw herself into the Bièvre River a few days later. Choosing a spider, a creature so adept at threading, to represent her mother offers us a personal association that she first explored in a drawing of 1947 and that was later to become a recurring motif.

But Maman has far greater potency than simply being an unconventional if tender tribute to her mother’s craft and dexterity. As well as being a cathartic means to channel her grief, an often cited incident earlier in Bourgeois’ life, the betrayal of her father, is also woven within. When she was eleven years old she discovered that her governess was her father’s mistress. Reviewed with this in mind, Maman begins unravelling into a subtext ripe for psychoanalysis. In other works, she has bared explicit reference to this event with titles like The Destruction of the Father. Here in Tokyo, Maman now becomes a decidedly more venomous arachnid, loaded with implied violence, with the potential for cannibalism; it seems to confess to a certain vengeance.

No doubt the throngs of shoppers that pass Maman recognise it be the dramatic spectacle it is. This edition of sculptures has been so widely exhibited internationally that the results of doing an image search online vaguely resembles a B-Movie invasion. From London to Bilbao, Ottawa to Zurich, Hamburg to Buenos Ares, Washington to Tokyo, its popularity seems astounding given that it is made from the tragedy of a bereaved and deceived daughter who devoted decades honing an object born of traumas. The only sadder possibility might have been an empty sac.

Maman is certainly the most refined version she made of her subject. It’s a compelling narrative rooted in the experiences of formative adolescence and young adulthood which were developed into a sophisticated personal symbolism that evades obvious assumptions. And it’s a great photo opportunity too – it’s just that photography alone only begins to capture what it represents.

Nick West

Nick West