Enoshima and the Sands of Time

The photos in Eiichiro Sakata’s exhibition, “Enoshima,” showing at the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art through September 29th, are the product of the 16 summers from 1997 until 2012 that Sakata spent lumbering up and down Enoshima beach, heavy camera equipment in tow. His mission? To capture the portrait of the age he saw in the scattered possessions of the shore’s hectic but cheerful denizens. Sakata took inspiration from the temporarily abandoned towels, the food, the clothing, the toys, bags, sunblock, and other materialistic flotsam strewn about the sand. What moved him most, however, were the owners of these objects, who he writes “projected a pride and robustness in their uniqueness and an optimism for the future, displaying a strong, hidden radiance.”

These ebullient subjects are not your typical Japanese, nor are they whom you might expect Sakata to photograph. Sakata, who trained under fashion photographer Richard Avedon, rose to prominence with his portraits of heads of state and other celebrities. The people he met at Enoshima had their own distinct senses of confidence and style, but were unlikely to appear on the covers of Aera or Vogue. They were largely the bohemian type, their cohort including guitar makers, accessory designers, beauticians, the homeless, and ganguro girls in full panda-like makeup. They sported tattoos, body piercings, neon and mohawked hair. The sight of them elicited gasps and laughter from the group of conservatively dressed baby boomers visiting the museum on the same day I did.

What did Sakata see in these people and their shore-side items in disarray? Viewed in a pessimistic light, the images can seem grungy and depressing. They evoke the oppressive heat of Japan in summer and present scenes of cheap, disposable merchandise littered across a cigarette butt-filled beach. Moreover, they come from a period when Japan saw its post-war bubble deflate, a time when, as Hara Museum curator Atsuo Yasuda explained, “the rise of internet culture weakened social ties, natural disasters and globalization caused anxiety, and people’s senses of self and life were shaken on an individual level.” In this context, pictures of the sand and grime-covered trinkets of people on the outskirts of a receding society hardly inspire the hope Sakata espouses. Still, an optimistic interpretation cannot be so easily dismissed in light of Sakata’s skill and philosophy as a photographer.

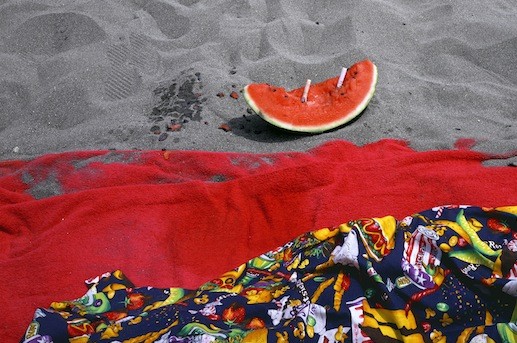

As works of photography, the ‘Enoshima’ pictures are punchy tableaus of vivid color and expert framing. The vibrant red of a half-eaten watermelon with cigarettes jutting out of it matches the hue of the towel beside it. The deep blue waves of the ocean are echoed in rumpled navy tarps on the beach. Sakata gets up close and personal with the beachgoers’ belongings, showing us the surprising style, humor, and humanity to be found in scenes that might look like blasé postcards if taken from a zoomed-out perspective. Furthermore, the photos live up to their billing as “people-less portraits,” giving us an idea of who these momentarily absent people are— if they are messy or neat, maximalist or minimalist, decorative or plain, spontaneous or careful.

The adroit execution of these photos is important because, as curator Yasuda pointed out to me, one of the purposes of photography is to crystallize moments that let us experience human feats of memory and imagination in the face of time’s cold irreversibility. Through the care and creativity of his photos, Sakata demonstrates that regardless of the headlines in the news, the points on the Nikkei, or the purported decline of society at large, there were still happy and free-spirited people reveling in moments of life and color worth remembering. His ability to find and show us this reality in seemingly inconsequential inanimate objects is what makes his eye as a photographer remarkable.

The ‘Enoshima’ series in some ways harkens back to Sakata’s earlier works, specifically his 1970 collection of street photography, ‘Just Wait,’ which photographed New Yorkers from all walks of life, and his 1995 series, ‘Amaranth.’ While ‘Amaranth’ focuses on the high-profile figures he photographed for Aera, it fits with his larger theme of a belief in humanity’s power and beauty as its title alludes to a flower that never fades. The book’s introduction explains that Sakata’s photography likens people to amaranth seeds, displaying their “lust for life that stems from their positive assessment of life.” Whether this optimism is warranted or even felt by Sakata’s subjects is another matter. Sakata is showing us the potential he himself sees in people, whether it manifests itself it the poignant gaze of a world leader or the leopard-print sandal of an unknown beach patron.

One of the more intriguing photos in the “Enoshima” series is of the beach’s lifeguard. In its blown-up version at the museum, you get the sense that this man is looking over something much larger than the stretch of sand and surf he’s responsible for—maybe the exhibition and its viewers, maybe the entire era Sakata is portraying. Possibly an incarnation of Benzaiten, Enoshima’s goddess of water, wisdom, and all things that flow, he is a beneficent presence. He sees all, knows all, and cares for all. Like Sakata, he is a clear-eyed witness of the age.