The Sound and Vision of Migration — James Joyce and the Photography of Leo Pellegatta

Maybe it was moving across America as a child or meeting the great, the good and the infamous as a journalist, but according to writer Joan Didion that inherent spirit to discover compels us to “tell ourselves stories in order to live.” The thirst for progress can quench uncertainty, but the mind is always drawn back home, even when living somewhere different will liberate the heart and mind. Didion sees the role of a writer or artist as crucial in understanding where we come from. It’s the power to document more than record, with the strength of reason to establish the individual at the center of a shifting story much greater than any place, or part of the world, and much more important than any rotating leadership. The fact is, we ‘need’ to tell stories in order to say we exist.

Photographer Leonardo Pellegatta’s recent exhibition “Ulysses: Open your eyes, now”, at Kanzan Gallery, began with its own journey embracing looseness and fluidity, looking for some innate truth through photography, sound and sculpture. His own journey, however, had taken chance encounter to mean more than mere incident, along a route from his birth place in Milan, towards New York to study at the School of Visual Arts, through Zurich and then Trieste, and more recently Tokyo, where he now lives. Giving the exhibition a physical backbone, his story wandered places, distracted by what he found, inventing and documenting images, objects and a sound installation that all paid homage to James Joyce’s novel Ulysses. Like each chapter of that book, the work turned to the metaphysical, beyond the flat, and towards ‘experience.’

The exhibition included objects and sound: a magic lantern (made in collaboration with Hiroko Shiratori); a series of hand made, palm-sized boxes (Notes for Proteus, 2015); several sound recordings by Nicolas Laferrerie, with one that played through an empty box of Cuban cigars (Music Box, 2015); and his most recent photograph of jellyfish encountered in a museum in Yamagata, inspiring the exhibition’s title phrase, Open your eyes now (2015) as a rousing call to reinvigorate and re-engage the world beyond image and representation, and see things on their own terms, or, at the very least Leo’s.

Published in 1922, Ulysses follows Leopold Bloom, along with the younger artist-poet Stephen Dedalus, for an entire day in Dublin, Ireland. The book was structured around Homer’s Greek poem, The Odyssey and used the ‘astrological’ title of each chapter to compose 24 hours in Leopold’s life. Yet an enclosed time, upon an enclosed island, is liberated in this text by the sea, offering Leopold a language of his own, however erratic and unfathomable, and reason to imagine something lay beyond Ireland’s periphery and the sea’s horizon. During the talk event on the 23rd January, Pellegatta along with writer Shinji Ishii spoke little of the work itself, and turned their attention to the role of Joyce’s language and how it helped mark out the exhibition as an ongoing environment, frequently referring back to the photographs on the wall. Navigation, the stars, and the sea are found in the flow of text that follows Joyce’s journey, and are held as universal motifs no matter where we are in the world. A previous incarnation of the magic lantern had been shown in Golden Gai, under the title The Sun Shines for You Today (2014) a subliminal reference to the celestial, and Golden Gai as a refuge for those that miss the last train. Being separated from one’s home is also the condition of migration, a state which, not only Joyce, but many Irish encountered.

The talk paid reference to the importance of first names and the meanings they carried, with characters becoming as important as places. Pellegatta’s name would become a metaphor for constant connection, with Leo, Leopold, and the Swiss art collector Leo Koenders, who was the first to suggest the artist try reading James Joyce. Joyce had been introduced as an itinerant traveler who never returned to Ireland, but who had once lived in Trieste, not far from Pellegratta’s home in Milan, from where he began writing what would later become Ulysses. Trieste was noted for its lack of domination by a single church, having a mixed cultural history, and a growing population of Jewish and Serbian migrants, provocateurs, fascists and avant-garde thinkers at the turn of the Century. This cultural frenzy compelled Joyce as much as it did Pellegatta, when he encountered a recital group in Zurich that would read Ulysses like a mantra each day, taking a year to finish the book, and then start all over again.

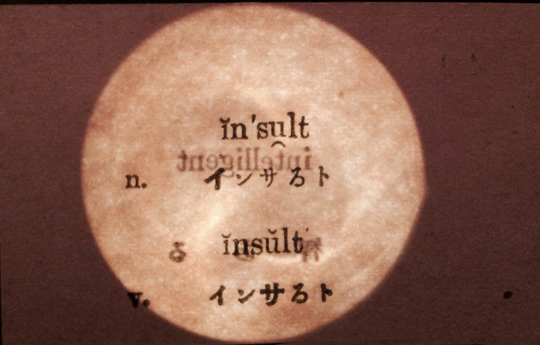

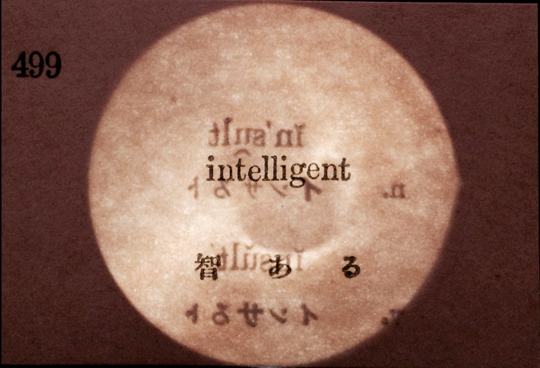

However text translates, be it in Italian or Japanese, you can’t help but wonder the significance the book carried with repeated reading. In Italian Ulysses is apparently lifeless. In Japanese, it is impenetrable or prone to mood swings of it’s own. For Finnegan’s Wake, one of at least three Japanese translations recasts the opening and closing phrase of “riverrun”*1, as “the sound of war,” an invented word in English reinvented in Japanese as something peculiar and uncommon. Sound as image ran together as if hand-in-hand. Images looked up through architecture (Pantheon, and The Oracle) or out, through gaps in walls (Modality of the Visible-Duino, 1 to 3), isolated a disembodied ear (SIRENS), a primordial fog (The Unknown), while all the time gave substance to Laferrerie’s sound-track in the background as the magic lantern sat discreetly at the center of the gallery. The Trieste square of Bloom’s Walk #1, embodied the same gentle ambiguity while the old Panama cigar box soundtrack gathered together field recordings from the sea, ambient guitar, and the voice of Joyce happily reciting Ulysses. As the magic lantern was cranked and rotated it sounded as much like a ship in water, with the lantern proving its own navigation and way to read and see the photographs that wrapped around it. Each image came from an old Taisho-period card game. Japanese was written phonetically one side, with English on the other, now and again giving way to some playful mistakes and wonderful misreadings— one card read “Intelligent” on one side, with “Insult” on the other.

Intelligent / Insult (Photo: Leo Pellegatta)

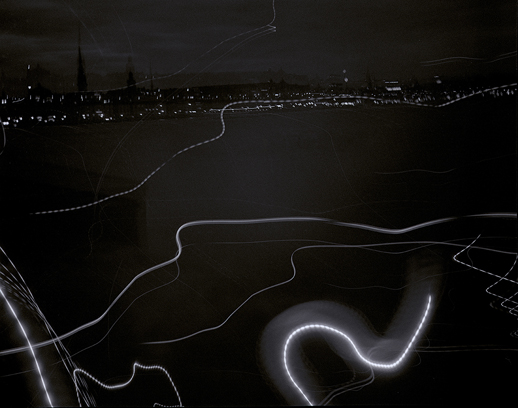

In Japan, Joyce has been revered especially amongst literary scholars, writers and film makers alike. Joyce’s writing has warranted some radical translation in contrast. Writer Ryunosuke Akutagawa, attempted to adapt fragments of Joyce’s earlier writing under the title Dedalus*2, while Akira Kurosawa adapted Rashomon from Akutagawa’s short stories. Kurosawa could be thought of as a ‘filmic’ cousin to Joyce, both in terms of a wavering perspective and how his camera gives the both wind and rain a presence and character of their own. Even with Pellegatta’s exhibition, Joyce’s figurative ‘sea’ was bound in the artist’s own collection of elements held together under the mark of constant change: the confused narrator (the sound of Joyce reciting, and words threaded from little photographic boxes); the varying climate of wavering sound (the sound of the sea and guitar); suggested tobacco smoke (the upturned cigar box, or darkroom experiments laid over pinhole photographs); or even mist rolling in from the Baltic Sea (long exposures taken at night in Stockholm Bay).

The peripatetic and displaced has frequently arisen as a theme in Pellegatta’s work as seen in the book Circo (2009), an ode to the traveling circus from Milan that he followed, shooting from the wings each night before, during and after each performance. More recently he has worked with a camp for children evacuated from Fukushima, following them for weekends away and some welcomed distraction from the anxiety and worry back home. In an early review of Ulysses written in 1922, Edward Wilson called the book, “the effect of unedited minds, drifting aimlessly along, from one triviality to another, confused and diverted by memory, by sensation, and by inhibition.” With Pellegatta’s first photograph shot at night above water (Ithaca), and the last taken amongst sea life below (Open your eyes now), the show shared the awareness he placed on sensing detail and expanding his view of the world along the way. All the while I was reminded of home and where I came from, revitalized by what was unique and new, and the experience of slowly reliving Leo’s story through my own presence.

Leo Pellegatta, Ulysses: Open your eyes, now, Kanzan Gallery, Tokyo. January 8–31, 2016

Notes

*1 http://p-www.iwate-pu.ac.jp/~acro-ito/Joycean_Essays/FW_2JapTranslations.html

“The first Chinese characters,”川走” (senso) expresses “river+run” which also reminds the Japanese readers of “war” (senso) by its sound. Yanase’s translation begins with the new Japanese word ”川走” which is not a common Japanese phrase just as “riverrun” is not in any English dictionary except the OED as a “nonce-word.” As Yanase explains, many wars are described in Finnegans Wake, the war between Adam and Eve, between Cain and Abel, between Brian Boru and the Danes, between Napoleon and Wellington, between life and death, between words, between languages, etc (FS 95-96). As many Japanese readers often raise a question, “Why did Yanase make this strange Japanese word, while there is no implication for “war” in the original word ‘riverrun’?” The answer is: Because Yanase translated not only the word but also Joyce’s “style” here: The word “川走” exemplifies how Yanase translated Finnegans Wake into Japanese.”

*2 http://p-www.iwate-pu.ac.jp/~acro-ito/Joycean_Essays/U_Japan.html

“James Joyce was first introduced to Japan by Yonejiro Noguchi’s article about A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in 1918 (Gakuto the literary magazine, March 1918 issue). The next year Ryunosuke Akutagawa, one of the most famous novelists at that time, bought two books of James Joyce including A Portrait. He was much impressed with Joyce’s technique, especially the boy narrator of its first chapter: Later he tried to translate some fragments of the novel under the title “Dedalus.”

Stuart Munro

Stuart Munro