Ikko Narahara’s Postwar Planet

Ikko Narahara’s career as a photographer began by looking up at the sky. It was August 15th 1945, and in the patch of blue where the 13-year-old was used to seeing fighter jets, on that day marking WWII’s end for Japan he viewed only open expanse. This visual symbol of peace represented nothingness for Narahara, a loss of direction, but it was precisely in this void that he found a new path: a search for national and humanistic identity in the postwar era.

Narahara, a contemporary of 20th century photographers Eikoh Hosoe and Shomei Tomatsu, is the subject of Fujifilm Square’s two-part exhibition “Where Time Has Vanished.” The first installment ending July 31st is titled “Journey to a Land So Near Yet So Far” and features photos from 1954–1970, when Narahara established his innovative style of documentary from a personal perspective in series such as Mukokuseki-chi (Stateless Land) and Okoku (Domains). “Beyond View” (August 1st–September 30th) surveys work from 1970–2002 with collections including Fukkatsu (Resurrection) and Inner Flower. These series focus on experimental photography incorporating X-ray images and visual effects replicating double vision, a condition Narahara personally experienced. Displaying approximately 20 photographs in each session, the show’s size reflects the venue’s compact space while offering a succinct and satisfying overview of Narahara’s career. Admission is free.

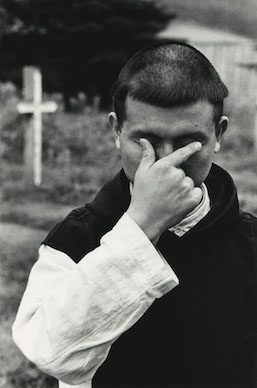

“Journey to a Land So Near Yet So Far” opens with a shot of a spaceship blasting off, chosen by curator Yuki Osawa not only because it speaks to the postwar era, but also embodies the nature of Narahara as a photographer: he is something like a being from outer space exploring Earth, discovering what humans are and how they live. One way he does this is by looking for parallel themes in diverse places. In the dramatic and haunting black and white shots of Domains, he examines intersections of solitude and solidarity in a monastery and in a women’s prison. The people in these photos appear simultaneously archetypal and alone, and Narahara’s gaze is one of fascination but remove.

This sense of looking from the outside in extends from humanity at large to nationality. In Japanesque, Narahara grappled with the meaning of postwar Japaneseness, a search that became more poignant and perplexing for him after time spent in Europe and the U.S. The cover photo of Japanesque shows an uplifted kimono blooming over the nude bottom half of its wearer, an image symbolic of the Japan’s hidden beauty, which Narahara hoped to find by revisiting tradition. Yet he realized the complexity – if not impossibility – of such an idealistic pursuit. Images of Mt. Fuji, swords, geisha, and the like appear at times exoticized, others probing, and often disorienting in warped, split-frame, and fish-eye perspectives. It is as if returning from abroad was like seeing Japan from a mirror turned at different angles. Rather than merely offering up clichés as a desperate grab at national identity, however, Narahara uses his feeling of disequilibrium to explore cultural fabrication vs. reality.

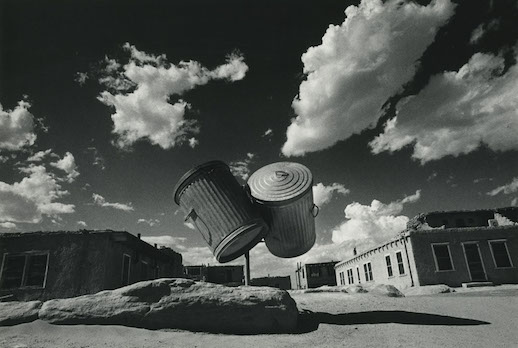

Ultimately, the line between fictional and real seems to be where Narahara finds a true home, as seen in surrealist images from the U.S. in Where Time Has Vanished and in meditations on his own body in Inner Flower and Double Vision. In these series, entwined trash cans dance in the air and an X-ray captures the strange beauty of a skeletal hand holding a rose. When life is no longer regimented by air raids and war drills, he seems to realize, all kinds of wonder can emerge.