Don’t Lie

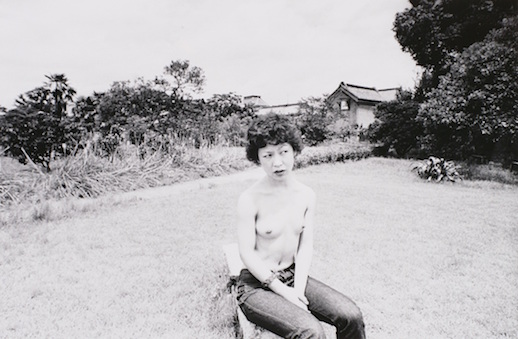

“Araki Nobuyoshi: Sentimental Journey 1971–2017–,” also now on at TOP Museum, is another show grappling with themes of death and communication. Araki, the postwar provocateur obsessed with eros and thanatos, established his career with Sentimental Journey (1971), a candid account of his honeymoon with wife Yoko. This series produced a masterpiece shot of Yoko curled up peacefully on a boat, an image alluding to voyage to the afterlife, and perhaps even rebirth. In the five decades since, Araki has been in constant communication with the vital forces and vast mysteries of life via his lens.

At the retrospective’s press opening Araki declared, “I’m at an age to ask if I’ve used all the talent god has given me.” These are gifts he has largely channeled into I-Photography, an intimate, often erotic, sometimes banal genre documenting anything and everything from street shots, to his cat Chiro, to the deaths of his parents. This style has been compared to Nan Goldin’s ‘The Ballad of Sexual Dependency’ and derives from a sharp break with commercial photography. After losing interest in glossy, superficial images meant to sell, Araki left Dentsu, Japan’s largest advertising firm. (“Actually I was fired,” he clarifies). He gets to the heart of his departure and his propulsion toward I-Photography in the prologue to ‘Sentimental Journey’:

It’s simply a deluge of fashion photographs, but the faces that appear there, the naked skin that appears, the private lives that appear, the scenery that appears are all lies, that’s what I can’t bear. These photographs are different from those lying photographs. This Sentimental Journey is my love and resolution as a photographer.

Araki has long identified “love” as his creative impetus, a statement that might raise eyebrows coming from a photographer also associated with erotic bondage shots. Yet looking at his body of work as a whole – and at this exhibition in particular – it is also reasonable to infer that this is an artist who understands, like the lines in the Robert Frost poem, “Earth’s the right place for love.”

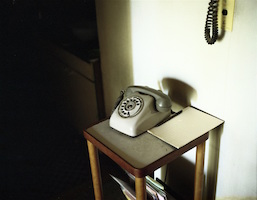

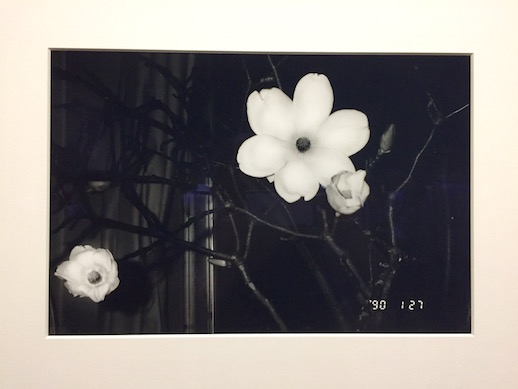

Nowhere is Araki’s heart more openly on display than in the collection ‘Winter Journey,’ an account of the months leading up to Yoko’s death from cancer. In what Juergen Teller describes as “maybe the most black and white photo ever,” Araki holds his bedridden wife’s hand, the framing juxtaposing his black suit with her white hospital clothes in an image of life and death right beside each other, united in love. He stopped during the ‘Winter Journey’ section of the tour to point out another photograph of white flowers in Yoko’s hospital room. “They bloomed the very day she died,” he elegiacally noted. “That’s what flowers do.”

The final shot in ‘Winter Journey’ is its pièce de résistance. Dated 90/2/1, five days after Yoko’s death, it shows the black and white Chiro frolicking in the snow, his front legs submerged with hind paws and tail raised, a picture of vitality and joy in a cold, fleeting landscape. It’s as if the words from the Vampire Weekend song Don’t Lie were written just for him:

Don’t lie, I want ‘em to know

God’s loves die young, is he ready to go?

It’s the last time running through snow

Where the vaults are full and the fire is bold

I want to know, does it bother you?

The low click of the ticking clock…

There’s a headstone right in front of you

And everyone I know…

There’s a lifetime right in front of you

And everyone I know

After ‘Winter Journey’ comes a section of the show with the wall inscription: “After the death of my wife, all I did was take photographs of the sky.” Images of skies painted over in vivid, sometimes impulsive, sometimes neatly linear colors are displayed. There is also a projection of 3,000 sky shots taken from Araki’s balcony. Surely for him, these are attempts at communication with his departed wife, or perhaps with the universe itself. We seem to have entered another realm after transcending the lusts and agonies of an intimately documented life.

At the end of the opening Araki once more addressed the crowd. The band Pathos had serenaded us with a saxophone tribute to his work, and Araki stepped forward to say, “This show has been about seeing how much I have loved, and how much I have been loved. Looking at it, I think I can say I’ve gotten out of life what I’ve poured into it.” This is a sentiment worth an appraisal – an honest one – by all of us still on this end of our journeys.