Oku-Noto Triennale: Contemporary Art at the Far Edge of Japan

Suzu 2017: Oku-Noto Triennale the inaugural edition of art festival to be held every three years on a peninsular tip of western Japan. Centered around the small Ishikawa Prefecture city of Suzu and its surrounding coastal towns, the event is an hour by plane and a world away from Tokyo. Boasting idyllic scenes of farmers harvesting rice on satoyama terraced mountain paddies with breathtaking satoumi ocean vistas, this is both a prime and somewhat surprising location for a contemporary art festival.

It is not without precedent, however. Its organizer is Fram Kitagawa, an art director known for festivals like the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale, which will mark its seventh session next year with artworks dotting the mountains of Niigata Prefecture. Kitagawa’s vision for these rural, site-specific events is a shift away from urban and profit-driven art towards creativity that reconnects locals and introduces outsiders to the natural environments and cultural histories of areas that have fallen by the wayside.

Oku-Noto Triennale is no different. Like Kitagawa’s other projects, it is a star-artist studded festival closely planned with and largely run by long-time residents. The Noto natives who lead its bus tours and stamp the “passports” at the sites its installations have personally ridden the waves of industrialization and depopulation, experiencing their hometowns’ rises and declines along with it. They attended the now-shuttered elementary schools and cheered at the openings of now-defunct train stations on tracks overrun with grass. Here are a few of the works they can show you at this year’s Oku-Noto Triennale, running through October 22.

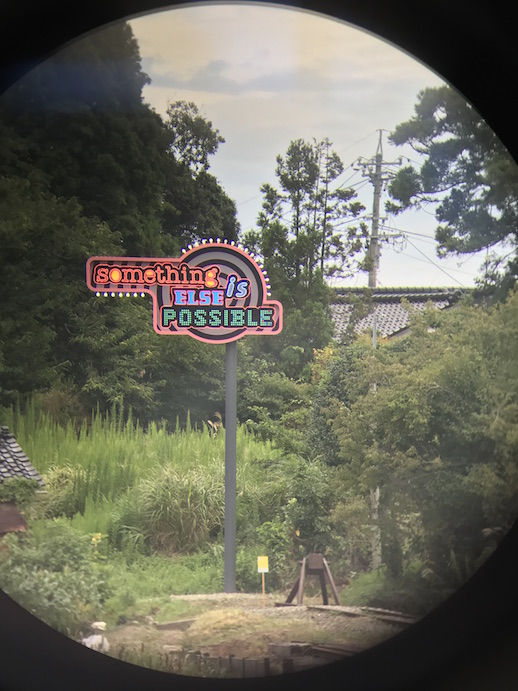

Maybe the most symbolic work of this entire sprawling metaphor of a festival is Tobias Rehberger’s “Something Else is Possible.” It also uses Noto’s abandoned railroad tracks in a nod to where we’ve arrived as a late-capitalist society. Yet its titular punchline dares to offer a suggestion of redemption, however ambiguous. This work could also be interpreted cynically, of course, as a harbinger of futility and false hope. But walking along the tracks – literally to the end of the line – and seeing the writing in lights, it’s hard not to feel at least a little lifted. Even in a land and an age of deep disillusionment.