Getting Scrambled at Spiral

In 1991, the art critic Noi Sawaragi published Simulationism, declaring originality a bygone ideal for contemporary art. He likened the artist to a grave robber freely taking from the slagheap of history, as well as a DJ splicing together so many signs without referents to make something new. Here’s his call to arms from the book: “Don’t be afraid, just steal!” This is a good frame of mind to be in when viewing Lu Yang’s current solo show at Spiral, a collection of video art that brings together Buddhist, Hindu and Christian iconography, cognitive psychology, otaku culture, and electronic music. The immediate effect is overwhelming and in tune with the chaos and social fragmentation that characterize our times. Making sense of work by Lu Yang, however, requires the viewer to dig deeper into the intermingling of disparate symbols and tropes in each video.

“Electromagnetic Brainology” represents far more than a harmonious merging of “Eastern” spiritual ideals with contemporary science. Yes, much of the work does deal with religious themes including theories of consciousness deriving from the Yogahara Buddhist school (唯識派), as well as the Mandalas of esoteric Buddhism (密教). Yes, it positions these alongside contemporary theories of the mind and neural science. And yes, Pop Buddhism oftentimes stresses the synonymity of the two. In Lu Yang’s work, however, they mix uneasily — there is no resolution, only discord between drastically different explanations of experience. All you can do is wade your way through the ceaseless stream of unfixed symbols. All the while, animated images of the artist dance to trap and house beats and Hindu and Buddhist deities come to uncannily resemble idols. Or is it the other way around? Although Yang’s work explores a variety of themes, this review provides a closer look into two central ones: the relationship between religion and science, and otaku culture.

Lu Yang’s 2015 Delusional Mandala provides a conceptual base for understanding recurrent images and symbols in many of the other videos, including the show’s title works Electromagnetic Brainology and Electromagnetic Brainology – Brain Control Messenger. The 17-minute Delusional Mandala shows an avatar of the artist being subjected to (among other things) stereotactic surgery. Electrodes stimulate her brain while subtitles provide a medical-materialistic rationale for her convulsing face: “The operation target of refractory mental disorders is mainly the limbic system…” By the targeting of isolated regions in her brain, the (simulated) artist experiences a wide range of emotions, pleasures and pains, until a certain “perfect” configuration of stimulations is achieved and the word “God” flashes across the screen.

The surgical device then transfigures into a crown. The nature of the subtitles changes too, and we are now exposed to Yogahara terminology: manas-vijnana represents the formation of the artist’s ego through its latching on to what is generated by her storehouse of consciousness, or alaya-vijnana (an accrual of karma generated through all past lives). There is a fundamental instability in this switch; Are we to understand Yang’s religious experience as purely biological, as simply a series of neurological interactions in the brain? Or, does the religious experience supercede the medical-materialistic explanation, which now appears flimsy in comparision to the moral dimensions of the religious explanation? Of course there is no answer: the crown reveals a tear in the fabric of contemporary experience that everyone must account for differently. It is a reoccuring theme throughout the rest of the show, worn by both superhero idols and Tantric deities turned dancers.

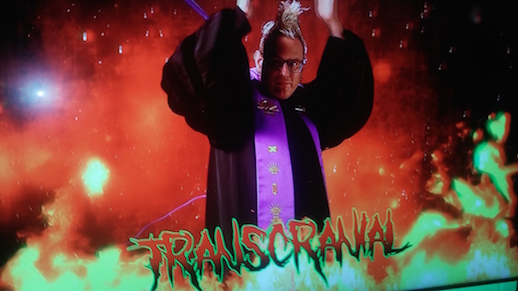

This gulf between the religious and medical-materialistic explanations is recreated in another one of the show’s works: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Exorcism (2017). In this video, a patient with Tourette Syndrome is cynically “treated” by a doctor in a white frock via stereotactic surgery (though it resembles torture more than anything else). In the next scene, the doctor becomes an exorcist battling a demon inside the former patient in a tokusatsu special effects style, and frenetic thrash metal sets in. While we once might have contented ourselves with a simple explanation of mental illness as a misfiring of chemicals in the brain and nothing else, something rings hollow in the smug confidence of such an explanation today.

As mentioned, Lu Yang’s work is more than just a dialectic between Buddhism and contemporary science: this becomes quickly apparent in her 2016 work Lu Yang Delusional Crime and Punishment. The work showcases a bizarre eschtalogical bricolage of Judeo-Christian, Buddhist and popculture themes. In one scene, the viewer experiences a creation account reminescent of the Old Testament with God creating man; later, Lucifer in goat-form makes an appearance. Hell is also modeled on one of the Buddhist six realms of existence (六道) that all beings constantly reincarnate through until they reach nirvana. Perhaps to skirt the risk of making the work seem too serious, there are also mundane, pop cultural references interspersed throughout: in one scene the artist is damned to labor indefinitely on obsidian exercise equipment with fire and brimstone for company. Just as you correlate the symbolism into one narrative of suffering, she adds another ingredient into the miserable pot and off you go again trying to find a new center.

As much as Lu Yang is interested in the interplay of religion and science, she also shows devotion to contemporary otaku culture. Here, Hiroki Azuma’s 2001 book Database Animals provides a useful clue in deciphering the relationship between otaku culture and her work. According to Azuma, otaku culture is not a unique product of Japan, but simply represents one of many manifestations of post-modernity — this description echoes in Lu Yang’s transnational, decentralized use of otaku imagery. While a Japanese viewer might recall the neon chaos of Akihabara, viewers in other locales could easily look within their own local otaku cultures to find equivalent sites or imagery.

With the death of modernity and narratives of progress, otaku are no longer interested in overarching storylines, instead being content to consume fragmented characters, places and concepts. Azuma calls this phenomenon Kyara-Moe (キャラ萌). Underlying this postmodern phenomenon is the concept of the database. Unlike plots and stories that impose themselves on the viewer, the databases so popular with otaku represent infinite permutations and iterations that each individual can rearrange in whatever order preferred. In short, databases represent the yearning for customizability so prevalent in contemporary culture.

In Wrathful King Kong Core (2015), a tantric deity is meticulously diagrammed in a manner that recalls the database or the avatar in an RPG. The slightly monotone narrator meticulously explains each of the items it holds, before moving on to connect its terrible wrath with a human’s neurological capacity for anger. What stands out in this work is the interchangeability of all the items documented. The emphasis on any one item is arbitrary and collectively they could be presented in any order (or rather, whatever order the viewer or artist wishes). Through this piece, we see Buddhist iconography absorbed in the virtual world — what comes to mind through this shift is the gamer’s desultory inventorying of or even fetishizing of an avatar’s arsenal and identity.

More generally, the exhibit can be read as a randomly generated, freely changing configuration of Akihabara idols, dance groups, and Buddhist imagery (a smattering of all the databases of contemporary culture). Lu Yang even collaborates with reality TV star Chanmomo to create a battle scene between the idol and an evil skull with an exposed brain in Electromagnetic Brainology — Brain Control Messenger (2018). For the other title work, Electromagnetic Brainology, elemental gods from Buddhism and Hinduism are seen dancing together in playful homage to the synchronized dance Para Para. The supposed chaos in these descriptions becomes more palatable if the viewer imagines all the combinations deriving from the database — the artist simply programs her desires and dreams into this atomized storehouse of contemporary culture and off the generated images go like so many ghosts flickering across the screen.

Jeremy Woolsey

Jeremy Woolsey