Ghosts of the Avant-Garde

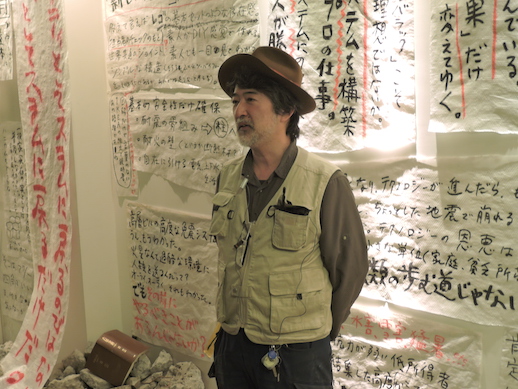

Ground No Plan is at once an exercise in unrealizable city planning – complete with swaying, flaccid obelisks and a mock Shinjuku Gyoen park – and a retrospective of the last ten years of Makoto Aida’s work. The show is sponsored by the Obayashi Foundation, which provides funding to artists who “examine and investigate” problems facing urban areas from a non-urban planning perspective. While it’s true that Aida has been interested in city planning since at least 2008, when he released a memorandum in humorously old-fashioned orthography entreating the mayor of Tokyo to invest in waterways (a staple of old Edo), one would be hard-pressed to say that he’s laboring to pose any kind of concrete change or alternative, let alone “investigate” anything.

Rather, Aida is an artist who uses city planning to subvert the utopian underpinnings of the discipline altogether (in short, to destroy city planning). What we get instead is a deranged vision of a city founded completely on negation, a city that couldn’t, and indeed shouldn’t, be created. The theme of city planning becomes a way for him to further his campaign of agitation, but whom is he provoking, and to what end? Below are a couple types of the polemics Aida employs in “Ground No Plan.”

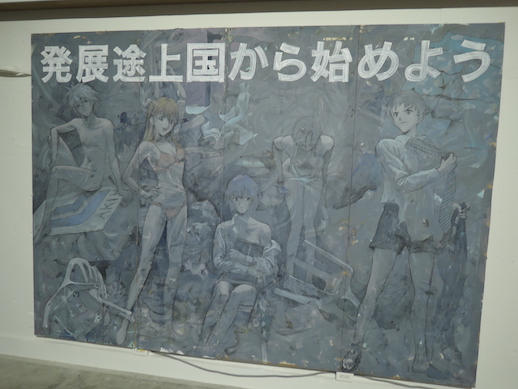

Walking through the post-apocalyptic basement floor of the Aoyama Crystal Building with its graffiti-covered walls and strewn-about lawn furniture, rubble and dictionaries, one stumbles on a large painting of characters from the anime Neon Genesis Evangelion and a phrase painted across the top of the canvas: “Starting with Developing Countries”. To fully understand this painting, it’s helpful to refer to Aida’s 2016 essay I Can’t Write “Confessions of Love”. In the essay, the artist discusses his philosophy of masturbation (i.e., that masturbation is not an alternative to sex but actually the goal of life itself) and sarcastically praises the Japanese government’s “Cool Japan” efforts to export Japanese culture, specifically anime and manga. He goes so far as to say that governments should invest in fostering this culture to solve the global crisis of overpopulation. Of course, no one, including Aida, takes these words seriously. What he does in this painting and essay is attack the “Cool Japan” cultural policy as well as the pretentious delusions of those in industrial countries trying to “save” the global South. It would be as absurd to say that he’s “investigating” ways to combat the overpopulation as it would be to say that the exhibition is an endeavor to develop a vision of a Tokyo for the future.

Aida’s sarcasm, however, doesn’t neatly allow the liberal left to scoff at the perversity of cultural nationalism and walk away with a clean conscience. Heavily influenced by writers such as Yukio Mishima and Ozamu Dazai, he has made a career of parodying all sides of Japan’s political spectrum. To do so, however, he often resorts to creating caricatures of conservative figures or concepts to paradoxically antagonize the left. This practice dates back to at least his 1995 Somewhat Right-Wing (なんとなくウヨク) performance, where he drew large “traditional” calligraphy characters, signaling the perennially despised return to tradition (原点回帰) to critique the dominance of liberal values in art at the time (and arguably still today). This practice can be summed up in Aida’s hatred of “Mr. and Ms. Justice” (正義君たち) – people who endlessly blast their opinions without looking at the ambiguities and complexities beneath the surface that complicate such indignation.

This spirit is continued in “Ground No Plan” through Video of a Man Who Calls Himself the Prime Minister of Japan Speaking at an International Assembly (2014), which caused controversy over censorship in 2015 when it was shown along with a manifesto addressed to the Ministry of Education. The work features Aida dressed as Prime Minister Shinzo Abe giving a speech encouraging all countries to pursue a policy of isolationism. He speaks in halting English, parodying at once the nationalist tendencies of the LDP party (especially in light of the upcoming “cosmopolitan” Olympics) and those who would deny the presence of Abe and other politicians we’d rather ignore. Pointing and laughing at Aida’s works from a comfy position of moral superiority in this sense is equivalent to pointing and laughing at yourself. Of course, this work also is shot through with self-deprecation: Aida counts himself as one of the least competent English speakers in the Japanese art world.

The video Artistic Dandy (2018) shows Aida dressed up as avant-gardist Joseph Bueys drunkenly singing in a karaoke room. Text on the adjacent wall reads (in translation): “Oh Beuys! Your generation was so nice. Artists could be sparkly frauds. Oh Beuys! Your generation was so nice. Artists could be sparkly gurus!”

Here we have a concrete example of the (ir)reverence for the self-serious mission of the avant-garde, as well as the recognition of this mission being lost (or rather, that it never really existed in the first place – it was just one of many silly myths we still drool over). Aida dresses the whole thing as a cynical gag, so it comes across as a mere slap in the face to Bueys and his project. (Aida also walked around on opening night in the same attire).

This is not the first time Aida has taken potshots at famous artists: in a 2008 exhibit, he displayed a parody of the painter Kenjiro Okazaki’s abstract style, paired with a title that attacked the critic Akira Asada. Reflecting on his choice, he wrote:

“I don’t bully the weak…Akira Asada and Kenjiro Okazaki are strong. Even if I attack them, it’s only my effort that shatters in the process…This is just my favorite “self-destructing material.” If I don’t explode in the process, and instead do damage to my opponent, then the whole thing fails as art.”

Of course, the legacy of Bueys is secure, and it is precisely because of this that Aida mounts an attack on the artist and his rather (seen from our time) grandiose aspirations. The secret venom that we all hold towards authority comes through in this piece.

There is another side to this story, naturally. Young Japanese artists may come to this exhibit and be jealous of Aida’s flippant and aggressive approach. The reality is that he made it in a time when it was perhaps easier to make it. With the saturation of artists and the relative stagnation of the domestic art market, it has only become more difficult to get your foot in the door. Art schools churn out more and more artists with no clear idea of how to succeed. A paradigm of the avant-garde thus remains: It is the duty of each generation to displace the previous generation’s dreams and ideologies to carve out a new space for themselves. That much hasn’t changed, and Aida would be the first to acknowledge this. In this sense, he gleefully awaits his own destruction in the (near?) future. We can only wonder what form it will take, and by whom it will be handed down.

Jeremy Woolsey

Jeremy Woolsey