Crossings on the 52nd Floor

There is a certain grandeur at the Mori Art Museum that commands (if just a little) respect when visiting. To situate what is a rather large museum on the 52nd floor of a skyscraper is quite a feat in itself, but it can also be a huge and somewhat overwhelming pedestal on which to make equally grand claims. Inevitably, common sense would have it that the higher you place something, the more dramatically it will fall.

So, with the 2007 instalment of the “Roppongi Crossing” exhibition we find a show tottering rather dangerously atop its prestigious position. Of course, the general response, as with most survey shows, has been mixed and due to the large number of participating artists and the restricted lengths of most review columns, formal critique is made rather difficult. So let’s address the slippery question that the show seems to be asking of itself and of its viewers: ‘What is art?’ This eternally problematic question may not be one that comes up during everyday conversation for most people, but the organizers here would seem to hope that it is. Their answer is that ‘Art’ exists in the process of crossing over with something else. The curatorial team that put this show together, Kazuo Amano, Natsumi Araki, Noi Sawaragi and Naoki Sato, has essentially brought together work made in a whole range of disciplines – from design to computer games to crafts and so on – under the banner of ‘Crossings’ and hails all of the people behind this work as ‘artists’. As Naoki Sato states in the exhibition catalogue:

It is not about what art crosses with that concerns us [sic] surely the point is that art is what emerges when two different things cross.1

These words conjure up images of curators working like mad scientists, bolting together a Frankenstein-like display. When Natsumi Araki points out that ‘the first motivation’ for selecting the artists was ‘Which artist do you like best?’2 you know that trouble might be brewing away like some bizarre potion and that the result could be fairly repulsive. This is not to say that a genetically mutated flower cannot be beautiful, but it is still somewhat ‘unnatural’.

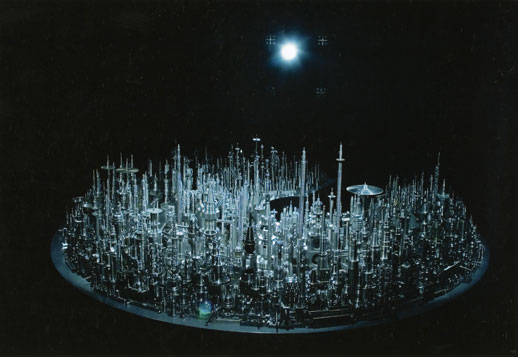

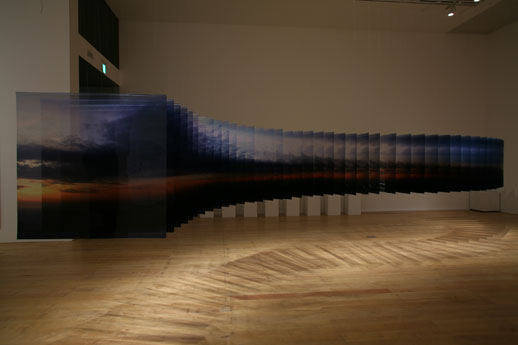

So what of these ‘Crossings’? What artworks are we presented with as conclusive examples of the work of ‘artists’? Sadly, the exhibition is composed of a ‘hit or miss’ range of work. One of the significant ‘hits’ is the inclusion of Keiichi Ikemizu, an artist who, through his clever public-centred works commands as much respect as Yoko Ono and On Kawara. Kiyoto Maruryama, one of the few remaining bath house painters, is also a welcome inclusion that draws attention to a ‘dying’ art form. However, it’s ironic that the heart of these works isn’t actually present in the exhibition itself: Ikemizu’s representative work within the museum’s walls is a corpse in comparison to his public installation in Roppongi High School and Maruyama’s bathhouse painting isn’t even displayed in the major gallery space at all, overlooking instead the entrance’s escalators.

Unfortunately, the exhibition’s attempt at including younger artists produces much of the ‘misses’ as they pale in the presence of such experienced individuals. The accompanying texts only make it worse, employing far too much rhetoric to describe the works. Unnecessarily pretentious descriptions such as “These household goods, reborn into a new form of beauty at the hands of Higashionna, are at times pure nostalgia” (Yuichi Higashionna) or “Using the slightest of modifications to throw social conventions into upheaval” (Iichiro Tanaka) tended to make me cringe. Furthermore, both the display texts and the exhibition catalogue left me with the feeling that I was having an opinion forced onto me. Sentences like “Viewers are struck by the detail…” (Yoshio Yoshimura) or the “works are marked by the special care given to an object’s surface, which is what people first notice when something enters their field of vision” (Kohei Nawa) come across as assumptions that try to make up for the viewers’ lack of familiarity with the artists’ work. Assumptions in art are never a good idea and yet they seem to form the core of Naohiro Ukawa’s wind machine if you believe the text: “based on the assumption that Hurricane Katrina… is sealed inside the typhoon apparatus… Ukawa has created a space within his machine where all the paper money in the world can be sent to dance in the wind”. Rather, what has been created here is a cliché, a fairground attraction of sorts that is almost sickening to the stomach.

In some aspects, I do agree with Sato about art being ‘that’ which exists in the interstice and not the medium itself. Yet my initial steps into the art world twelve years ago were always grounded in the understanding that art and design are different. Art is that which exists in the empty void; it is the ineffable that will always be beyond the reach of the artist. Yet the word ‘Design’, to quote the philosopher Vilém Flusser, “fits into a context involving cunning and craftiness. A designer is someone who is artful or wily, a plotter setting traps.”3 This is not to say that what the individuals have done in their respective careers is futile or doesn’t command respect, but the contrived bringing together of their works by the curators to put a finger on the pulse of Japanese contemporary art creates the same effect as when you push too hard for too long on your pulse – it hurts. What is elevated here is not ‘art’ but a ‘designed’ exhibition, which presents a variety of talented people as show ponies; the ‘art’ never really got in the same elevator. But of course, to refer to European etymologies when defining Japanese contemporary art is to leave myself wide open to criticism; one that Noi Sawaragi emphasises:

The word ‘art’ only came to Japan in the Meiji Period, For example, works by Hokusai weren’t defined as ‘art’ or ‘design’; they were both. So the division comes about with the opening to the West. With this exhibition, I wanted to go back to that idea of them not being separate.4

Sawaragi’s statement is very true but the works he refers to were made during a period of isolation and those in this exhibition are not. Sato speaks also of art being a global economy and if this is the case, surely it should be measured against the same yardstick?

Perhaps I’m being too cynical? Maybe I was not communicating with the exhibition on the right level? Perhaps I was being too naïve in my understanding of what an artwork can be? Or perhaps I was taking too much of a lofty view of some of the tired clichés in the show. In any case, whether this exhibition gets its point across depends on how the public receive it, not the writers or the critics. Despite some of my criticisms of the catalogue text, I found it to be more useful and actually more interesting than the exhibition itself, and this is one of the key points where the show fails terribly. The exhibition aims to reach out to people and yet prices them out of the means to connect with the artwork on a deeper level: how many casual visitors are going to shell out nearly 3,000 yen for the catalogue when they have already paid 1,500 yen for the entry? The show is big, it is glossy and it is ‘spectacular’ in the Debordian context of the word, but it is also shallow: a novelty. As the curators rightfully point out, the world of art is becoming more popular to those with less knowledge. In Britain, a media frenzy engulfs the Turner Prize every year, and the inescapable question of ‘is this art?’ rings hollow and tired bells in the lives of the people to the point where the whole spectacle has become a joke. The illusionist David Blaine’s stunts are also an example of the ‘spectacular’ capturing the people’s attention and subsequently inviting speculative criticism. Is this to be the fate of “Roppongi Crossing”? Ironically, when Blaine spent 44 days without food in a clear plastic box suspended over the River Thames in London and declared it ‘performance art’5, the public’s reaction was to throw things at him, direct laser pointers at him, and even use a remote-controlled toy helicopter to fly a hamburger around him. Perhaps the “Crossing” show’s 52nd storey plinth only guarantees that it will be shot at.

So, what left the most resonating impression in my mind after I had left? Whilst watching Kohei Kobayashi’s video sequence of someone counting fruit in and out of a bag, a young boy of no more than three years old was trying to guess the fruit in the sequence. He ventured a “mikan?” (tangerine) and “nashi?” (pear) to his mother, hoping she would be able to answer his question. Needless to say, she couldn’t. Later his father asked him if he could understand the video, to which the boy cried to the tune of laughter “wakaranai!” (“I don’t get it”). As Sato finalizes in the exhibition catalogue:

I must say that I don’t think it’s a bad thing if increasing exposure to the term ‘art’ prompts people to begin, little by little, to question what exactly this thing called art is.

True enough, but first we would have to hope they are put in a position where they are able to take it seriously. If not, well, wakaranai.

—

1 Sato, N. (2007) Crossings as the Source of the Value of Art, in Roppongi Crossing 2007: Future Beats in Japanese Contemporary Art, Exhibition Catalogue, p33

2 Cited in Eubank, D. (2007) Design Meets Art at ‘Roppongi Crossing’ Japan Times, [Internet] http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/fa20071018r1.html [accessed 27th October 2007]

3 Flusser, V. (1995) On the Word Design: An Etymological Essay, Design Issues: Vol.11, No.3 Autumn 1995, p50.

4 Cited in Eubank, D. (2007) Design Meets Art at ‘Roppongi Crossing’ Japan Times, [Internet] http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/fa20071018r1.html [accessed 27th October 2007]

5 Cited in Collins, H and Roberts, T. (2003) David Blaine: ‘I’d like to go as far as I can’, CNN [Internet] http://www.cnn.com/2003/SHOWBIZ/08/30/cnna.david.blaine/index.html [accessed 27th October 2007]

Gary McLeod

Gary McLeod