All Tied Up in Rope

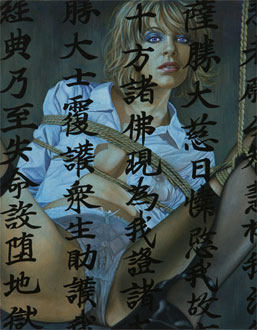

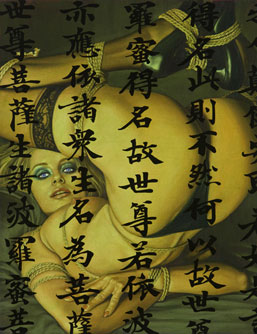

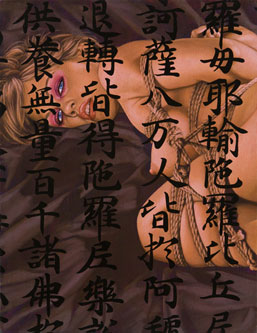

Kimonos, half-naked women, rope. These may sound like the ingredients for an Araki photograph, but in “Black, Sutra and the Rest” currently showing at Takahashi Collection, artist Ken Hamaguchi subverts this age-old recipe of Japanese eroticism by using buxom Western models in place for the submissive, demure Japanese girls traditionally bound up in such portraiture. In the exhibition, which features dozens of identically-composed small paintings showing mostly naked blonde girls in bondage (some in high-school uniforms or kimonos) with Buddhist sutra written over the surface in black ink, Hamaguchi not only condemns the commoditization of sexual desire and pornography, but also seems to imply that a certain aggression or devious nature of Western sexual expression is tainting the more delicate or complex Japanese concept of eroticism.

Bondage, specifically using rope (known as kinbaku in Japanese) is not only seen as a tool for sadomasochistic play, but like tea ceremonies and other such cultural traditions involving complex techniques and aesthetic rules, kinbaku’s intricate way of rendering the tied body immobile is also considered an art form of sorts. What immediately comes to mind at first glance of Hamaguchi’s paintings are Nobuyoshi Araki’s photography series featuring Japanese women in vivid kimonos (and less) staring at the camera, almost expressionless, in various – at times painful or embarrassing – kinbaku poses. Here, however, in contrast to the sultry but almost passive-looking girls in Araki’s portraits, Hamaguchi’s blondes are seductive – almost aggressively so.

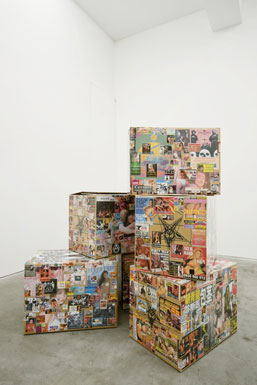

The girls (whom, although not identical, all resemble the stereotype of the all-American cheerleader) smile and tease, as if enjoying not only the act of being tied up and the gaze of the viewer, but the power that comes with it. Hamaguchi does not seem to expect viewers to project their fantasies onto the vulnerable female, but instead presents women who actively use their bodies and sexuality to enact and seduce. The rope becomes not a restriction, but a vehicle. The tone is mirrored in a small mound of cardboard boxes stacked in the corner of the room, plastered with advertisements for phone sex and prostitution featuring naked girls in suggestive poses — notably, most of these have been taken from Western magazines and newspapers. The female body is simultaneously empowered and commoditized, marveled at and abused.

It is not clear whether it is the very notion of this aggressive sexuality that Hamaguchi is critical of, or specifically that of the “foreign female”, but in any case the paintings reveal Hamaguchi’s suspicion for his subjects. The girls’ eyes at times glow red or green amidst their ominous backdrop of muddy blues, reds and greys, making them look almost monstrous or other-worldly. He also introduces the notion of censorship in the way that he conscientiously blurs out the genitals, much like how they are censored in explicit photographs and videos. Usually such mozaiku cover the underlying image of genitals. Here, however, the genitals do not even exist in the first place; rather they have been substituted by the connoted “nothingness” of the blur.

As if “cleansing” the images of their evil sins, each painting has been covered with black sutra. The juxtaposition of the somber black Japanese kanji with the tied up blonde girls peering behind them creates a potent image of condemnation. Simultaneously, the mixing of the Caucasian girls and Japanese elements leaves a strange aftertaste; the kimonos and uniforms that the girls wear can only maintain their sexual connotations through the historic and cultural significance placed on them, and can only be activated when somebody from that very culture adorns them. Thus, the subtlety of demure Japanese eroticism is lost on these blondes, however whether Hamaguchi goes as far as placing blame on a Westernized sexuality or female role infiltrating Japanese culture is hard to tell. In any case, this intricate play of seduction, power, and condemnation in this series makes it a unique and confronting exhibition, from which no doubt every viewer will take home a different opinion.

Note: This exhibition is only open on Saturdays

Lena Oishi

Lena Oishi