Adventures in Outer Space

Watari-um is very much not a white cube kind of gallery and so it is perfectly suited to Shimabuku, who is very much not a white cube kind of artist. The German-based artist’s full name is Michihiro Shimabuku; names, his own and his works’, are a way of introducing his investigation of self-knowledge. And the original Japanese title of the exhibition is revealing when translated: “to the people of planet art” is one rough rendition. Travel and adventure are suggested, as is a sense of fun. Get on board the spaceship because I’m gonna take you for a ride!

And that is very much what this exhibition feels like. Though its scope and distance is, in spite of reoccurring star motifs, not exactly intergalactic, it nevertheless takes the visitor on a merry-go-round of the building’s facility (a memorable piece of architecture by Mario Botta) and consistently surprises our expectations. It is as much actor-less promenade theatre as a standard art show.

You take the lift up to the second floor and, upon alighting, are faced with several pieces of fruit and veg floating incongruously inside two tanks. Looking round for explanation you find none, but just catch the title of the piece on the lift walls before the doors close: ‘Something to Float / Something to Sink’ (2008). Positioned cleverly in the corner you then turn back to the work and view it intimately. You indeed begin to see what is floating and what isn’t. It becomes a game and, while not as startling as Hirst’s shark, is still an unsettling but amusing starting point.

Elsewhere on the floor you find on the walls the title of one of the main works as well as a general theme: “do something you didn’t plan to do”. This extends to a video showing a German woman trying to sing a Japanese song she does not understand and, perhaps most curiously, a screen showing the artist receiving golfing tuition, next to a real shooting range where visitors can go in and take a swing. Posters around the wall encourage you to find a Big Issue seller in the area; there are benches to sit on and watch the golfers. This is certainly not art where you just stand and stare at the painting. Against the large wall window that offers views of the neighbourhood is another screen, showing Shimabuku’s mountaintop fish feast with a group of Koreans. This continues the ideas of communication and language barriers being overcome – something that reoccurs several times in different locales – and here the medium is that well-loved Japanese past time of eating a meal.

From here where do you go? Why, outside of course, traversing the staircase and up to the third floor. Opening the door you are alarmed to hear a voice coming from the corner saying, “I am a box…I am happy that I am a box.” After a moment of disconcertion you see in fact that it is indeed a box but with a speaker inside. You feel almost embarrassed to stand alone and listen to this object, but that is what you do because the monologue is a hilarious bittersweet masterpiece.

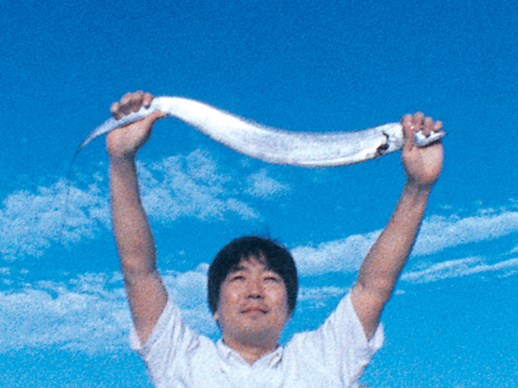

This floor continues Shimabuku’s exploits in foreign lands and his attempts to knock down the barriers that prevent humans from communicating. A video shows him fishing in Italy to catch octopus using a traditional ceramic pot, one he made himself. You go deeper into the space by avoiding more food, this time placed on a board in the shape of a constellation. The far wall has another film; like ‘Born as a Box’ (2001), ‘Flying Me’ (2006) further explores self-identity and egoism, by showing the artist taking a kite literally of himself (or at least a life-size photograph made into a kite) and trying to fly it on the beach of what appears to be Los Angeles. Combining Mr. Bean-like eccentricity and visual flair, the passersby seem not to know what to make of the whole performance.

Whack, whack. To your left a window lets you look down at the golf below. You return to the door (“I am a box,” you hear again); a sign says you need to take the lift to get to the top floor. But there are still more stairs, so, intrepid, giggling with the other visitors, total strangers but all drawn together in a camaraderie by this art adventure, you go back outside. As you head to the roof a notice tells you that tea can be ordered direct to the stairwell. Reaching the top you look around for the piece that is apparently somewhere here; by the time you have found the eponymous creature of ‘Elephant Planet’ (2008) you also hear its honk.

Inside, the fourth floor is a very mellow, quiet place, and feels like a come-down from a fast and crazy ride. Onions spell out another constellation. A large carpeted room shows a huge projection of ‘Shimabuku’s Fish & Chips’ (2006), transfusing the space with blue light and soft, gentle music. You sit, relaxed, and watch what seems to be another tongue-in-cheek work, depicting a potato floating in the sea, nibbled by fish and bobbing along for infinity.

Making ample and imaginative use of the Museum’s unusual triangular architecture, the balance between the tangible, sculpture and video works in this exhibition is very admirable. All too often an exhibition with a lot of video screens becomes a passive experience, visitors slumped in their seats dozing. This is a testament to the Museum’s superb curation. The fact that you can come twice on the same ticket only adds to your enjoyment, knowing all the time you can come back to play another day.

Shimabuku, “New Works”

From 2008-12-12 To 2009-03-15

Adults ¥1000, Students ¥800

at Watari-um

3-7-6 Jingumae, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo 150-0001

Phone: 03-3402-3001 Fax: 03-3405-7714

From 11:00 to 19:00

Wednesdays closing at 21:00

Closed on Mondays

William Andrews

William Andrews