Re-Thinking Human Ecology After 3.11

This year’s second edition of the Dojima River Biennale was inspired by an earlier exhibition that curator Takayo Iida organized at the Eye of Gyre gallery in the Gyre Building on Tokyo’s Omotesando in June 2008, called “Art and Ecology: Ecosophy in Practice I.” While that show had uncannily coincided with the G8 summit at Lake Toya in Hokkaido, which focused on coordinated measures to curb the runaway advance of global warming and other environmental issues, this exhibition three years later on the banks of the Dojima river in Osaka bookends Japan’s own “environmental” crisis of March 11, as well as the ensuing debate and discussion over what sort of remedial action is possible or feasible.

Participants at Lake Toya had to wrestle with an inevitable eventuality, and reconcile it with past failures to commit more fully to confronting the political and economic interests that have ravaged the environment. In contrast, much of the debate in the wake of the Tohoku earthquake has spurred a frantic reassessment of energy policy and the hidden costs and dangers of power generation and distribution, nuclear or otherwise.

As Iida explained at the opening reception on July 22, both exhibitions included works that represent artistic interpretations of the ideas set forth in French psychoanalyst Félix Guattari’s “The Three Ecologies” (1992). In this book, Guattari argues for an expanded definition of “ecology” that would encompass not only the biological environment customarily associated with the term, but also the psychological, emotional and social conditions that govern both interhuman relations and our connections with the natural world.

In some cases these ideas were embodied quite literally. New York-based artist Noriko Ambe’s ‘Cutting Book Series: A Study of Ecosophia’ (2011) consists of a thoroughly lacerated copy of Guattari’s text riddled with intestine cuts and slashes, its gouged-out “keywords” breaking away from their context through lines of flight that tried to squiggle free of the book. These rhizome-like strands resembled a physical approximation of a hypertext whose keywords sought to teleport themselves to another cyber-space, but the format seemed to lag behind its subject, given the explosive proliferation of e-books and readers in the last few years.

A broader visual representation of how we perceive and relate to nature came from Daisuke Ohba, whose five-sectioned acrylic on cotton canvas ‘FOREST #1’ (2009) depicts a glossy, pastel-colored forest and its tangle of scattered foliage that quivered under the spotlights. Made using a “polarized light bar,” Ohba’s paintings come across as two-dimensional holograms that materialize and dissipate depending on the angle of the light hitting their surface. Alternatively, these works might be read as photoreactive all-overs whose shifting hues imply a materiality that continually evades our grasp, just like the inscrutable nature that we constantly struggle to comprehend.

A standout was Mariko Mori and Kengo Kuma’s intriguing collaborative effort, ‘White Hole’ (2011). This immersive installation consists of a convex acrylic panel installed with intelligent LEDs networked to an observatory at the University of Kyoto that serve as a visual index of the cosmic energy of disintegrating stars torn apart by the massive gravity surrounding black holes, translating them into faint swirls of light that seem to have been reborn in another, metaphysical dimension. Around Mori’s telescopic screen, Kengo Kuma constructed a bulbous cavern made out of knobbly bits of urethane foam (99% air, originally developed as an energy-efficient material for “marshmallow” insulated homes), suggesting that we are only ever afforded a partial, detached glimpse of this primordial universe through an empirical process of contemplation.

Most of the architectural contributions to the exhibition, on the other hand, steered clear of the rhetoric of minor improvement and micro-customization common to the Japanese architects who have been gaining favorable attention abroad lately, such as Junya Ishigami, Atelier Bow-Wow and SANAA. These latter practitioners assert that all available plots of land in Japanese cities have been thoroughly exploited and densely saturated, leaving little room for grand gestures or comprehensive refurbishment. Instead, incremental improvements are achieved by opening up claustrophobic lots, bringing elements of nature and the outdoors inside the house, and so on.

If Fujimura’s response seems essentially Modernist in spirit and akin to Le Corbusier’s proposals for postwar collective housing projects, it also acknowledges that any architectural project undertaken to ameliorate the effects of a crisis like Fukushima can no longer afford to stop at the level of individual micro-politics and fine-tuning “pet architecture.” Faced with the inescapably physical dimensions of this refugee evacuation and the disruption of man-made ecologies, our corrective mechanisms must also rise to approximate the massive scale of the damage inflicted.

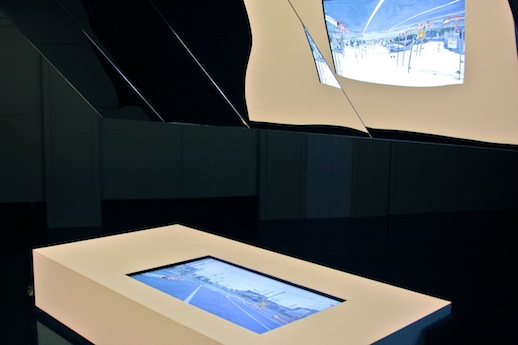

Elsewhere, ‘Namie0420’ (2011), an unsettling sound and video installation by Keiichiro Shibuya, Kenshu Shintsubo and Yoshihide Asaco, memorializes the transience and fragility of man-made infrastructure, and our psychological states that rise and fall along with it. The work depicts a deserted, post-exodus traffic junction in the town of Namie, in Fukushima prefecture, with the hard-edged glint and throb of an electronic soundtrack hanging over it. The only movement comes from a flashing amber traffic light, desperately telegraphing a message of caution against an inscrutable danger whose dimensions are essentially ungraspable.

By visualizing the complete evacuation of a human ecology and the paralysis of an infrastructural and technological one, ‘Namie0420’ captures something of the sinister sense of stasis that still blankets huge swathes of the quake- and tsunami-stricken areas. For a population inured to more than six decades of prosperity and peace, this malfunctioning piece of infrastructure is also a potent metaphor for the sickening sense of paralysis and systemic meltdown that now afflicts Japan’s environmental standards, food safety regulations, as well as the integrity of its government and media.

Although one might have wished for a slightly broader engagement with Guattari’s theories given the premise of the exhibition, “Ecosophia” is nonetheless a deftly timed reflection on the psychopathic trauma of a deeply fractured country grappling furiously with its worst national crisis since World War II.

Dojima River Biennale 2011 — “Ecosophia: Art and Architecture”

July 23 — August 21, 2011

Dojima River Forum, Osaka

Darryl Jingwen Wee

Darryl Jingwen Wee