GUTAI: A lesson in Japanese Art History

Entering the “GUTAI – The Spirit of an Era” exhibition at the National Art Center, Tokyo you pass through a doorway clad in an oversized sheet of torn gold paper; the feeling is that of having arrived after the event. For those who have even a very general notion of what ‘Gutai’ (often translated as “concrete”) is, this dramatic entrance is likely to chime with certain preconceptions. The gold remains are remnants of a 2012 reproduction by Tomohiko Murakami of Saburo Murakami’s ‘Entrance’, which originally appeared in the ‘1st Gutai Art Exhibition’ held at Ohara Hall, Toyko in 1955.

The first comprehensive retrospective of Gutai ever to be held in Tokyo, this exhibition includes around 150 works, centering on painting, photography, sculpture, installation and film. Anchored in Kansai and the Hanshin region, the group was inaugurated by Jiro Yoshihara and included sixteen additional members when it was established in 1954. After numerous member permutations, it was disbanded mere weeks after the abrupt passing of Yoshihara in 1972.

Set out in six chronological chapters, the exhibition takes a rather didactic approach, coming across as very informative, if a little dry at times, in the way it surveys the eighteen-year period. Beginning with an introduction to Gutai, the ‘art journal’ that marked their first major undertaking in January 1955 prior to their debut exhibition, the carefully presented trajectory though the history of the group poses few challenges to the canonical view held of them.

The Gutai manifesto (December 1956) specifies how their works are an investigation of the properties and possibilities of materials, taking an open and honest approach that avoids imposing the human spirit upon the characteristics of material, instead attempting to ‘bring it to life’. This sincerity and a bid to “[m]ake something that’s never been made before!” also led them to re-examine the spaces in which art was presented, namely palaces, salons and antique shops. According to Gutai member Shozo Shimamoto, early works by Kanayama were presented in the ‘1st Gutai Art Exhibition’ (1955) as ‘one part of the space in the venue’, and not simply as hermetically sealed works unto themselves.1 From the outset, the relationship between materials, works and the environment in which they are encountered was central to the spirit of Gutai.

Supporting the art historical framing, early Surrealist and figurative paintings by Yoshiharu are displayed in the third chapter, with connections to previous Japanese avant-garde movements such as Shirakaba-ha (White Birch Society) referenced in text panels. This provides a useful recalibration before the painting-heavy “Gutai Goes International 1957-1965” installment of the show that also includes a partial reconstruction of the Gutai Pinacotheca façade, which opened in 1962 and that functioned as the group’s exhibition space and headquarters until 1970. That painting was actually always a central part of Gutai production is communicated well, though there was an overwhelming move more towards painting and 2D production after the group’s relationship with Michel Tapié, an art dealer, curator and leading figure in the Art Informel movement, was established.

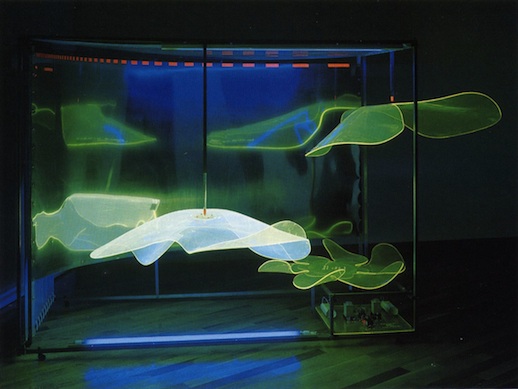

With 2012 marking forty years since the conclusion of Gutai, this exhibition could be taken as a celebration of their achievements. Uniformly weighting the three distinct phases of the group’s work, there is a bid to equate the value of the oft-overlooked latter years of Gutai production with the other more famous periods. Frequently disregarded due to their more ‘pop’ aesthetic, many of the later works were created by new members involved in the “15th Gutai Art Exhibition” (1965), their alternative styles a bid to avoid a Gutai ‘mannerism’ that was beginning to take hold. Put simply, the shift can be viewed as a move to ‘cool’ as opposed to ‘hot’ abstraction, embracing conditions of mass production and consumption.2 There are works that utilise acrylic and motors, repetitive geometric patterns and pastel or neon colours. In one room are three UV-lit kinetic sculptures, whilst numerous 2D works serving as Japanese precursors to Op Art hang on the gallery walls outside.3

This later period coincided with the rapid growth of the Japanese economy, iconized importantly by the “Progress and Harmony for Mankind”-themed Japan World Exposition held in Osaka in 1970. Over a three-day period there were spectacular performances as part of the “Gutai Art Festival” at the expo, their final large-scale public appearances. Films of these shown in the penultimate exhibition room give the impression of coming full circle, back to the early roots of Gutai where characters such as ‘The Red Men’ first appeared on stage in 1957.

The exhibition follows the recent Atsuko Tanaka show at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, and closes prior to the first U.S. retrospective devoted to the group, “Gutai: Splendid Playground”, that will be held at the Guggenheim in 2013. Presenting so many works from a lengthy period in such a straight-up fashion, the current exhibition arguably does not add much to the critical discourse on Gutai. However, as an introduction to a group somewhat neglected by Tokyo it educates viewers to this art from a post-atomic age, a timely showcase in a Japan in the throngs of another nuclear climate.

2 Ibid., p. 270

3 Ibid., p. 251

Jessica Jane Howard

Jessica Jane Howard