Filmic Diversions

In a cinema, the experience is nearly always the same, remaining unchanged since the early days of cinema. Mobile phones, tablets, laptops and televisions aside, for the most part we still sometimes sit inside a darkened room gazing at an expansive screen not much different from Thomas Edison’s “Black Maria”, his tar-black shed-cum-film studio used to create some of film’s earliest moments which, when enlarged on screen, spawned the original cinematic experience. Far from being Edison’s black box, and unlike the conventional cinema experience, walking through the double-layered curtain at Taka Ishii Gallery presents a moment of suspense, walking into a room and bearing witness to the possibility of something new, with what artist Toshiya Tsunoda describes as a landscape of sound and vision that’s more akin to a conversation between friends than somewhere defined by longitude and latitude coordinates.

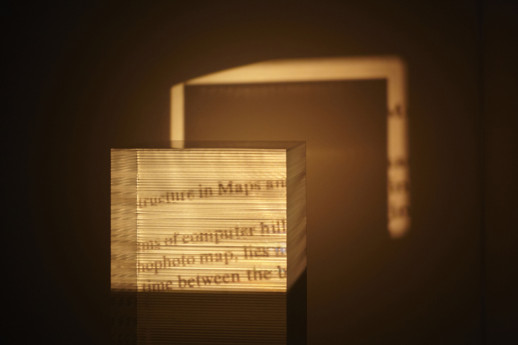

On the opening night of Tsunoda and Luke Fowler’s show, ‘Leader as Gutter’, the small group of expectant guests gathered to experience the show in the dimness of the gallery only lit by Luke Fowler’s film and the light leaking from his 16mm projector. The show’s title comes from that piece of film used to thread a projector–leader–aligned with a book’s spine–the gutter. As the film plays and the filmed pages turn, the combination of the two give rise to unexpected moments that reveal as much as they obscure.

At some point in the evening a man walks in, directed to the back of the plinth forming the screen and centrepiece of the installation. Film of someone reading is projected onto sandwiched sheets of acrylic, unevenly spilling onto the wall behind and liberally diffusing bits of stray light around the space. The man stops for a moment, peers at the back of the plinth then at the wall and then at everyone only to leave abruptly moments later. One by one the audience slowly walk to the back of the room to see what is was that had caught his attention so suddenly. This sudden spontaneous break in etiquette changed the nature of the whole show, a moment I am sure that both Fowler and Tsunoda would be happy with. That moment saw their installation go from being a film watched from a distance to an experience with everyone in the room, leaving the comfort of cinematic darkness and actively engaging in the installation.

Fowler’s and Tsunoda’s show comprises a number of elements that, if caught casually, can easily pass you by. The film focuses on disconnected passages from Arthur Howard Robinson’s The Nature of Maps: Essays Toward Understanding Maps and Mapping, a classic book from 1976 that considers cartography as a cognitive science, as much as a tool for communication and orientation. Sound wanders in and out of the gallery, making brief connections between the visual and audible. Photos near the gallery entrance take this idea of random association one step further. A half-frame camera places two images beside each other, each half a fragment, an object, a place, and figures in odd and engaging situations that suggests moments that have come and gone simply through the way each set of images are paired and arranged.

Fowler, a Scottish filmmaker, artist and musician who lives in Glasgow, was recently shortlisted in 2012 for the Turner Prize for his solo show at Edinburgh’s Inverleith House, showcasing his film All Divided Selves (2011) about underground psychiatrist R.D. Laing. Laing’s writing during the 1960s and ‘70s wrote about mental health and mental sickness by suggesting the feelings of alienation and depersonalization of people referred to as ‘mentally ill’ were in fact extraordinarily sane within an increasingly insane world. Figures like Laing were the outsiders of their time, responsible for much of the social and cultural revolutions happening in music and popular thought and culture, revolutions simply attributed to the musicians and makers of the day. Through Fowler’s previous work and augmented soundscapes, he argues for a reappraisal of their legacy using his own idiosyncratic, instinctive and improvised form of filmmaking.

Context plays an overall part in his work. His family has inspired his fascination with process and documentation. His mother’s career as a psychiatrist led him to use analogue recording techniques, just as she would use a tape recorder to document her interviews with patients. As a musician, he has been experimenting with sound and old analogue synthesizers in bands and through electronic music, which has in turn influenced the obvious sense of freedom, liberation and experimentation of his film work.

Tsunoda, a Yokohama-based sound-artist and musician, originally studied oil painting at Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, later focusing on field recordings and treating them like isolated landscapes much like his paintings. He combines single phenomena such as the sound of wind and rattling objects in his recordings and via installation work. His contribution to French filmmaker Gaspar Noe’s 2009 film Enter the Void — Filmy Feedback (Afternoon) — combines summer cicada with the sound of clapping hands and oscillating hiss. With his cerebral CD Temple Recordings he attaches microphones to the head of someone as they look out across a place of interest. Recording their head muscles moving and blood flowing, the resulting impression becomes a type of aural landscape in themselves. A previous collaboration with Fowler — Familial Readings — takes Tsunoda’s sonic narrowing combining single recordings into sound collage. His interest in landscapes developed from his time painting at university and has seen this interest blossom as he experiments with augmenting these subjective experiences through sound and visual work combined.

Both Tsunoda and Fowler have previously explored a disregard for the conventions of their respective disciplines with a previous installation Ridges on the Horizontal Plane (2011). Here two images fall on a screen, one either side, with the curtain screen made to gently billow by a neighboring fan. The images distort as they overlap and the screen cloth gently rubs against the strings of a piano creating a mixture of both sound and vision that demonstrates their mutual respect for each other as well as a fascination with the mechanics of perception and the collision of worldly phenomena.

By disregarding conventional approaches to presenting moving image, the central theme of their collaboration is revealed. This collaboration is as much a challenge to an audience as well as each other: it is one that asks how can a cinematic experience shine light on a new form of storytelling, expressing characters both real and imaginary, and aspects of their surrounding world. The filmed passages in Leader as Gutter are almost set as themes. “Conquest of space”; “Real World–raw data–maps”; “Structures in maps and mapping”– these subtle instructions that appear in the moving image mean little by themselves but together hint at a perceived world they map and the structures and system used to decode them.

Tsunoda himself goes out of his way to record and construct sounds that are difficult and challenging, not so easily consumed or recorded and sensitive to their context as well as the presence of other media. Both support, and as seen here, conflict in a situation they freely explore and exploit. He adds crucial sound, without which the installation would be less of an experience. Tsunoda brings the sense of experience through field recordings and augmented sounds that stealthily drop in and out of the gallery. Several times I wandered around the gallery trying to fathom which speaker the slow vibrations and ticking sounds came from. Tsunoda’s fascination with contextual landscape no doubt brings some of what is outside into the gallery. You, the viewer, are constantly pulled back and forth between things you think are part of the work and things you think pollute it. Fowler’s imagery hints at ways to navigate the show and their collaboration.

The show is a glorious mixture of ideas and pieces that work together and in opposition to one another. Sound and objects don’t obviously relate, but also don’t feel like they’re meant to either. You are forced to wander around the room to decipher and make sense of this union and find yourself asking whether the sound you just heard was part of the show or a noise from outside.

With enough time spent watching and absorbing this environment, the room becomes a map and the phrases appear like subtle instruction where you’re viewing the room rather than the film itself. Even light leaking from outside through the slit of the curtain becomes part of the scene. With the added spectre of a soundscape, the show is an experience that requires walking around to gather Fowler and Tsunoda’s scattered fragments of ‘raw data’, suggestions of things yet to happen heard through sounds from a distant future and images from a familiar past.

Stuart Munro

Stuart Munro