Finding the Lead Lines

Jesse Freeman is a Tokyo-based photographer, filmmaker, ikebanist, and all-around aesthete who calls his distinctive brand of minimalism “nothing in particular.” He spoke with TAB about his new role as a creative director, his first photo zine, and his growth as an artist just before his one-day photography exhibition, Jordan’s and a Gold Chain.

You’re just back from Stockholm. What’s your connection to Sweden, and what kind of creative projects did you get up to while there?

Back in 2008, I met a Swedish couple who became my first friends in Japan. They moved back around 2011 but I always planned on visiting, and now they’ve started Muro Scents. It’s a company that revolves around incense but also brings in lifestyle and creative design. They named me creative director and flew me out to work on that.

What’s it like collaborating internationally?

It’s interesting, because as the creative director I got to be around people who, anything I could think of, they can do. It’s a different way of creating with a commercial product in mind. It’s a lot of fun, and there are just certain things you can’t do on Skype.

You’re also involved in music through Muro Scents?

Right. The brand is about the full lifestyle, and the idea is if you’re at home and lighting incense, you want to inspire your surroundings and create an environment, which includes music. We have so many musician friends, so we’ve reached out to a few we really look up to. We’re starting with a guy based here, an artist named Mr. Tikini. We’ll be asking him to do more of the musical curation for the brand.

What else do you do as creative director?

Copyrights, slogans, campaigns. It’s a lot of writing, but my photography as well. I curated a hardcover book for their launch that’s going to feature my photography and writing. I was also able to line up two exhibitions of my work in Sweden at the end of July or early August while there. I’m not sure what I’m going to do with them, but one will definitely be for the photo zine, which Muro Scents sponsored.

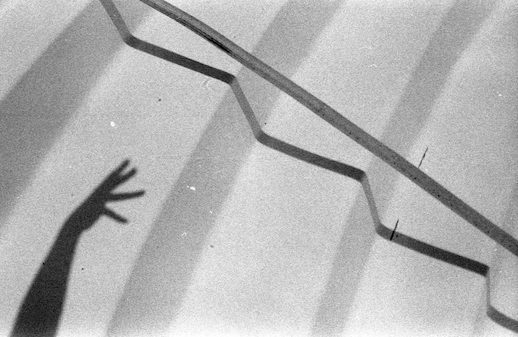

Yes. Let’s talk about Jordan’s and a Gold Chain, the photo zine you made with your friend and fellow photographer, the late Alani Cruz. You’ve written that it’s inspired by how Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane would riff off of each other’s music, and there’s a similar interplay in visuals here. How would you say your styles as photographers come together or contrast in JAAGC?

They come together in the responses we gave each other, but it’s definitely more the contrast. It was specific that he only did color. I’m mostly known for black and white and really don’t shoot color much. That was a huge contrast.

What I always loved about Alani’s style, though, is that he injects a lot of humor. It’s not overt… it’s a sensitivity to these everyday things he was able to express. I’m more academic or compositional, so it was kind of a balance of hot and cold. It was fun trying to get out of my zone and show my work in the context of his.

In JAAGC, sometimes the imagery is humorous, sometimes poetic, and sometimes it packs a real emotional punch. Obviously you and Cruz were communicating with each other through these photos. Do you think showing them in an exhibition will give them a meaning or dialogue different from what they have in the zine?

Definitely. For this exhibition, we actually have about 80 to 100 photos, and there are only 28 featured in the zine. After Alani died, his mother gave me his whole hard drive, so with this exhibition I’ll be able to show more of his high-quality images and new work.

But also with an exhibition, it’s just bigger and everyone’s able to look at it together. It creates a more group-based conversation than just looking at a book. And I think a lot of the small details can be missed in the zine, but when they’re blown up in front of you, you get to talking about them and you understand new interpretations. It’s about getting people together. When everyone is able to see it together, it does create a more authentic dialogue.

Do you see JAAGC as a tribute to Cruz, who passed away of cancer last year?

It’s definitely a tribute. We just had small ambitions for it, but the last time I saw him while he was still walking, we went up to his rooftop in Nakano. It was a group of us, and he pulled me aside and he said, “Can you get that done?”

It’s also a tribute in the sense that it was something he himself worked on. I will never try to release a collaboration that we didn’t do together, because the intention wouldn’t be there, and I’m not sure what the connotation would be. I’m happy that this is something we worked on together, that he expressed a desire to have finished.

Would you call Cruz a mentor of yours?

Yes, I would say that. If I ever had one, he would definitely be the closest. When he put out Rather Be Making Art Right Now, a zine of his photography, design work, and seen illustrations, which few people ever saw, I remember thinking, “How did he do that?” I learned photography through looking at that zine. I never would have told him that, and I never would have introduced him as “my mentor,” but that’s what he was.

What would you like people to know about Cruz as an artist and person?

This is difficult… certain people you meet, and you just know right away that they’re different. I really never met anyone like him. It’s easy to say that, but I never did. The way he observed things, and the way I’d see other people misinterpret the way he was, because he didn’t say much. He had this weird image to him. He abstained from anything that would change his mind state: he never drank, never smoked, never took caffeine. He was like a saint.

His whole thing was, he would rather make art. He would always be there for his friends, but had that loner sort of mentality. Some people are like shooting comets… You just have to appreciate them while they’re around.

JAAGC is just one example of your photography, which shows influences from street photography to Shoji Ueda, Man Ray, and recently the painter Vilhelm Hammershoi. I wonder, though, how would you describe own your style and its development?

When I started out with photography, I never had this “What do I shoot?” problem. I was like, oh, I want to do this shot by Nagisa Oshima, or another from some black and white film that I liked. I would try to mimic those. And of course, when you try to copy things you can’t, really. At a certain point I copied so much that I would tell people who I was referencing, and they wouldn’t see it. It just became its own work based on who I was, and I came to embrace that.

Any other ways your work has evolved?

Well, the ikebana’s gotten a lot better! I’ve gained a lot more confidence there. Also, I wasn’t into photography originally – I liked films. But after about a year I got into Cartier-Bresson and a lot of those early photographers and it sprawled from there. I guess the way it evolves is just…curiosity. I have a curiosity for something and I get into it and I start to see how I can relate it to what I do. I try to spontaneously let it happen or incorporate other elements. That’s why it’s “nothing in particular.” It’s a continual process of taking in more and turning it out in different mediums and forms. It’s definitely evolved in that sense.

You mentioned your ikebana, which has many of the stylistic elements of your photography: spare lines, careful attention to composition, the beauty of negative space. You’ve also noted how an artist can use scissors more than a pen as a means of expression. How else would you say the two art forms can influence each other?

With ikebana you’re going through four years of strict compositional training – you have your shin, your soe, your hikae, and jushi – your main line, second line, third line, and supporting lines, but it’s all about the space in between and anchoring a composition through lines. I’ve started getting commissions as an architectural photographer, and a lot of my skills there are what I learned from ikebana.

You told me before that one of your favorite filmmakers is Hiroshi Teshigahara, who quit making films to take over his family’s ikebana school. As a practitioner of ikebana yourself, do you think Teshigahara has influenced your own filmmaking?

To an extent. But more than that, he introduced me to the idea that filmmaking can translate into ikebana.

In both your film and your photography, you generally shoot more in black and white than in color. Is that an aesthetic choice or a natural tendency?

At first it was an aesthetic choice…black and white has a level of abstraction that color doesn’t. It was also practical – I can’t self-develop color in a dark room, and black and white is much faster and more economical.

At the same time, I see better in black and white. To me when you shoot color, that has to be an element of the composition. It’s something Alani could do. The associations he made between colors were so exciting. It’s also something that comes across well in film.

Right! I know you’re a huge admirer of the director Ozu, who did really interesting things with chromatic composition.

Ozu was amazing with color. I’ve always looked up to him and Godard for that. And Godard has that quote about how, when someone commented on the violence in his films, he responded with “It’s not blood, it’s red.” When I do something with color, it has to be ABOUT color. It can’t just be IN color.

Why would you say you’re so compositionally driven?

I guess it’s just personality. I’m kind of OCD in my house. I arrange all my bookshelves chronologically and by country. And with films, too. I try to organize everything to be as efficient as possible. I think that just naturally translates to my photography, which is always about, “How much can I exclude?”

Do you struggle with the call of when to trim a shot or leave something out of the frame?

No – for me it’s instinctual. If I were to shoot you right now and you were the subject, I would automatically look past you for framing lines, reflections. It’s very intuitive.

I think when you photograph something, you have to do it for two reasons: for what it is and for what else it is. That’s another difference I’ve seen from my earlier works. Now I only shoot a subject if I have something to bring to it.

You also write wonderful photobook reviews for Japan Camera Hunter. How do you find so many great collections?

I have a lot of good photographer friends, for instance John Sypal, who are like photobook encyclopedias, so I used go to the Tokyo’s photography museum with lists from them and just budget a day to that library – which a lot of people didn’t realize was amazing!

Do you have any favorite photobook stores in Tokyo?

If you know what you’re looking for, Book Off has the best deals. Also, So Books in Yoyogi Hachiman, whose owner is a great jazz fan. And of course making the rounds in Jimbocho.

What speaks to you in a photograph or collection of photography?

Well, Western photography’s always been about the single, powerful images, but Japanese photobooks were really the only ones in the world shot with the book in mind. When you get into them it’s so amazing, because they evoke these moods through highs and lows and a great flow.

It’s like with the idea of listening to The Greatest Hits of Miles Davis – you just shouldn’t do it. Davis would create an album and give it a certain mood, a theme, a style. When you cut it all up it doesn’t work. Japanese photographers understood this. Their editing – which me is the hardest thing to do in photography – and part of the reason JAAGC got started, is just beautiful. It’s like that Rothko quote about how painting lives in companionship, arising and expanding in the mind of the viewer. To me the most important thing in a work is creating a universe or atmosphere to bring the viewer into. When you can put together a theme and see it through, that’s the ultimate.

What are the differences between a photo zine and a photobook? Is a zine more experimental? Are there artistic merits to one or the other?

A zine is more experimental, less risk. It’s a smaller statement. They’re usually how street photographers gain any money from it… They’re also really fun and you get ideas. It’s a lot more playful, and when it’s playful you can achieve some amazing things.

But books are a whole other level – one that I’m not even thinking about for another couple of decades. There are just some things that I respect so much that I don’t want to touch yet. I know I’m not nearly at the level of say, Masahisa Fukase’s “Ravens.” When the stakes are that high it changes things. If you can play with those stakes and create something incredible, though, that’s going to be way more rewarding than experimentation.

So maybe we can’t expect a photobook just yet, but what other projects can we look forward to from you in the meantime?

I’ll be shooting a short film in Tachikawa on May 1st. The release date isn’t decided yet, but it’s going to have a hyper-realistic Romanian New Wave style. And I’ve got plans for a comic book based on a darkly existential horror story I wrote.

I also want to do a second zine with more of Alani’s photos. Then, for one of my Stockholm exhibitions, I’m thinking about a Dada, surrealist photography series about the period between WWI and WWII.

Thanks, Jesse! TAB can’t wait.

See work from Jordan’s and a Gold Chain and rare copies of photo zines by Cruz at the Tokyo Was Here Showroom on Sunday, April 17th. Address: 151-0053 Tokyo-to, Shibuya-ku, Yoyogi, 5 Chome−8−5 Yoyogi Pavilion