The Light and Shadows of Ei-Q

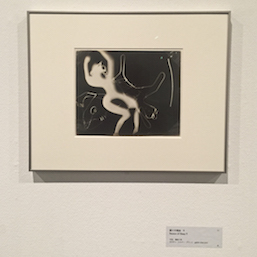

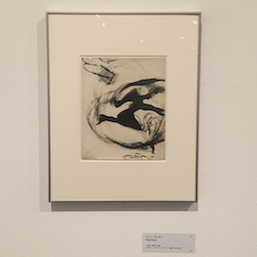

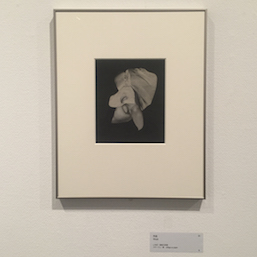

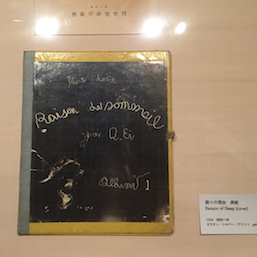

Collage and photograms were relatively new mediums in 1935, having been established only one or two decades previously. Many will be familiar with collage, but photograms in the digital age are if anything a lost art. Created entirely in the dark room, they are camera-less images made by placing objects on photo paper exposed to light. Man Ray pioneered the technique with readymade objects in the early 1920s, with Picasso and other artists dabbling with the medium later on. Photograms were quite short-lived as a popular art form, however, and have now faded into obscurity as a brief lesson in traditional photography classes that still deal in film. Ei-Q (real name: Hideo Sugita) used the technique as early as 1930, and we know from an essay of his that he was very much aware of Man Ray and the European avant-garde, so it never was done for sake of novelty. Instead, building on his concept of “real” (his perception of the realities of the age), he made cut outs of varying transparencies to create more intricate images he titled ‘Reason of Sleep.’ The result was a considerable gap between what he intended with these works and the way critics of the time received them.

The seismic shifts between the era that influenced Ei-Q’s ideas and the one he created his art in ultimately came to work against him. 1935-1937 was a transitional period for Japan culminating in an attempted coup d’état (the February 26th Incident of 1936), which contributed to a rise in nationalist sentiment and the civilian government becoming increasingly dominated by the military. Japan from the beginning of the 20th century was also a time of industrialization and change in the aftermath of victory in the Russo-Japanese War. Contrast this environment to Ei-Q’s formative years of the 1910s and 1920s, when Western influence had come to reach a new peak reflected in the arts, particularly in literature, with narratives that often dealt with the tug of war between tradition and modernity. We might also note the particular influence of the European avant-garde on one of the most famed writers of the period, Yasunari Kawabata, whose leap into the movement was most notable in A Page of Madness (1928), a surrealist silent film the author scripted.

By the time Ei-Q came to prominence this celebration of Western culture had been dampened, however, and the intensely individualistic artist faced the unfortunate scenario of being written off as a decade-late Man Ray follower, even though he had taken the concepts behind his photograms much further than anyone before him. Even today, the medium is still relegated to not much more than a forgotten gimmick or a novelty, precisely because no artist really sought to push its potential forward in its first decades. This blow was drastic to Ei-Q, causing his nervous breakdown and disillusionment with the Japanese art circles in general, before he returned to painting in a pointillist style and died relatively young at the age of 48.

It was the audiences’ failure to recognize the depth Ei-Q went into the medium of photograms and the labeling of him as a European follower that led to his fall. These circumstances make it pertinent for MOMAT to show such an artist. While Japanese culture is held in great esteem in the West and its synthesis by Western artists has also been much appreciated, there is a double standard for Japanese avant-garde artists of the late-19th and early-20th centuries who have referenced Western art in a similar manner. One artist to point to for comparison would be the surrealist writer Kobo Abe, who has been mostly written off by the West as a Kafka follower and is regarded a sub-tier below Kawabata or Dazai. However, one could argue Abe didn’t let this dismissal discourage him to the degree it did Ei-Q, whose legacy is having planted the seeds for other artists to stage some wonderful plays, find a voice in literature, and take his ideas to cinema with some amazing results. This curious, small-scale exhibition on the second floor of MOMAT provides clues into how it all started.