The Yebisu International Festival for Art & Alternative Visions 2018

Rafael Rozendaal: Into Time

The theme of this year’s Yebizo Festival is ‘Mapping the Invisible’ and Rafael Rozendaal has done exactly that, expressing a slice of the net in tangible form in his lenticular series ‘Into Time’. When thinking about the impact of invisible things on society at large, you cannot escape talking about the internet. In the introduction to his book net.art. Materialien zur Netzkunst, the German art critic and media theorist Tilman Baumgärtel defines the specific qualities of net.art as “connectivity, global reach, multimediality, immateriality, interactivity and egality”. Those definitions certainly apply to Rozendaal, a Dutch-Brazilian visual artist who uses the internet as his canvas and has been working with moving images on the web since 2000. [Connectivity]

The internet is a distraction for us all, but Rozendaal’s goal is to see how he can turn this distraction into art. His answer has been to create websites generating 60 million hits a year, in which he “abstracts the internet”. [Global reach]. A number of his websites and plugins work with a Chrome plugin called Abstract Browsing, which turns the sites in your browsing history into rectangles. [Interactivity] One of the first artists to sell websites as art, Rozendaal stipulates in the sales contracts that the sites must remain on public view and the owner must renew the domain registration annually. [Egality]

The pieces on display demonstrate how Rozendaal has expanded his oeuvre from the immateriality of the digital to multimedia material works. At the opening of Yebizo, the artist remarked that he “always had a talent for moving images” and was drawn to the lenticular medium as it is “somewhere between an object and a moving image”. Each lenticular painting is made from four very simple colour compositions with the lens material creating infinite combinations. The paintings are similar to a computer, but in this case the viewer is executing the algorithm. [Interactivity]

Despite the ubiquitousness of the internet, the web itself is of course not visible to us. Although we may be able to open up a computer and gaze inside, as technology advances by leaps and bounds, the true power of the machine lies not in its parts but at the quantum level, where particles can exist in a superposition of states, much like these lenticular images. As well as being interactive, colourful pieces of art, ‘Into Time’ captures the essence of the invisible beautifully – enough to tear you away from your smartphone’s social media for just enough time to appreciate it.

–Mac Salman

‘Into Time’ is on show in the Yebizo main program through Sunday, February 25.

The Invisible Myanmar New Wave

The theme of this year’s Yebisu International Festival for Art and Alternative Visions is “Mapping the Invisible”, gesturing to a cartography of the unseen world made visible by a media of light and shadow. In modern times, photography and cinema made visualizing the invisible possible. In the contemporary period, our fragile perception of reality has expanded as we have seen new media built to share objective information turn out to be machines manufacturing dubious truths. Yebizo’s program reflects this predicament and its wealth of possibilities through contemporary art exhibitions, symposiums, and film screenings.

In the film screening category, “New Wave of Myanmar Independent Cinema: Selected Films from Wathann Film Festival” illustrates how new media can repudiate dominant social structures that monopolize the manufacturing of truth. With access to affordable digital cameras and editing equipment, film has enabled young Burmese filmmakers to speak truth to power. Their counter-power demonstrates how reality can be manufactured and selected for public discourse. This raises the question, how can the disenfranchised empower themselves through narratives of reality and truth?

Myanmar has a long cinematic history. From 1920s through the early days of the military junta in 1962, Burmese cinema flourished with lavish productions and quality talents who also went abroad to share their skills in Indian and Japanese films. However, according to film historians, Myanmar’s golden years of cinema occurred in the 1950s, after the country revived itself quickly from the devastating Second World War. It was during this same period that the Myanmar Academy Awards were established. According to an interview in the Bangkok Post with Academy Award-winning actress Grace Swe Zin Htaik, who currently works as human rights advocate focusing on sex and HIV education, Burmese cinema slowly deteriorated before the beginning of 1980s, when heavy censorship was placed on filmmakers and the military junta agenda was aggressively pushed as the central theme for local film productions.

These restrictions virtually killed Myanmar’s cinema for many decades, but when the younger generation had the chance to access affordable new media technologies, some started shooting their own films and distributed their works on the black market through compact discs for home theater consumption, which was difficult for the military junta to control. Media scholar Keiko Sei (a guest programmer for Yebisu) researched this phenomenon, leading to her involvement in the production of a subversive documentary with footage of ordinary people recounting the Saffron Revolution in 2007. A couple of years later, Myanmar cinema in the field of documentary filmmaking officially made its debut.

The films from Myanmar shown in Yebisu are selected from the Wathann Film Festival, an independent platform showcasing local documentary filmmakers since 2011. According to Sei, these films mark a new wave in Myanmar’s cinema. Watching the films, seven in total, allows anyone the chance to experience the reality of Burmese everyday life, once denied by the military junta’s dominant truth.

–Jong Pairez

“New Wave of Myanmar Independent Cinema: Selected Films from Wathann Film Festival” will be screened for a final time at Yebizo at 11:30 a.m. on Saturday, February 24.

Mako Idemitsu “If Invisible, I Visualize”

Perhaps once even the most ardent feminist might have found Tampax footage combined with John Cage scores jarring. But now, as assaults on women’s rights and bodily autonomy come to fresh light daily, the work of avant-garde filmmaker Mako Idemitsu goes down like a good strong tonic. Addressing this year’s theme of “mapping the invisible,” Yebizo screens an omnibus of seven of Idemitsu’s short films under the title “If Invisible, I Visualize.”

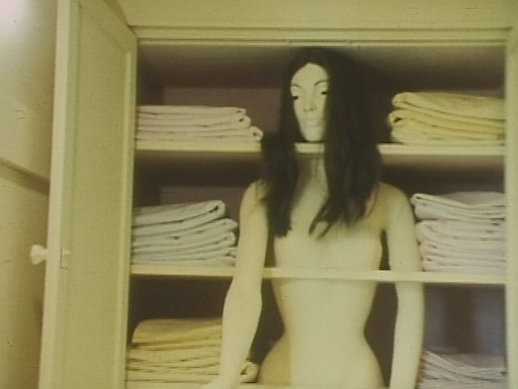

The ignored, the unspoken, and the taboo all wear different cloaks of invisibility, and Idemitsu’s films deal with all of these themes. Woman’s House (1972), filmed at the feminist base Womanhouse in L.A., gives us a feverish funhouse tour of the physical and domestic trappings of a woman’s life as it scans through a residence filled with fake boobs, fried eggs, used menstrual products, and a female mannequin trisected and installed in a linen closet. What a Woman Made (1973) dramatizes the journey of a tampon to a clinical voice-over by a man explaining the difference between boys and girls. “With girls…you don’t have to buy those toys that are good for developing individual traits. To develop girls’ individuality is rather harmful for them. Men hate women with strong personalities and don’t like to have them as their brides.” Donald Richie, who provided the English translation for the speech as well as its narration, matches the treacly condescension of the Japanese precisely. Hideo, It’s Me, Mama (1983) is a 27-minute tragicomedy about a mother so obsessed with her son she tailors every moment of her own life to his VHS-monitored existence. With its speechless black and white footage of a town where Idemitsu lived for eight years, At Santa Monica 3 (1975) seems strikingly unlike her storytelling videos, but as another landscape set to a minimalist soundtrack is a fitting companion to At Yukigaya 2 (1974) screened upstairs in the main program.

During a question and answer session on February 12, Idemitsu was asked about the relationship between her two types of films. “They’re separate,” she explained. “I wanted to portray womanhood with one and light with the other. I leave their similarities open to interpretation.” She also spoke about the creative constraints of filming and building an artistic career while raising children. “I had to work with the time, space, and equipment I had while taking care of my family. In doing so, I made films that men couldn’t.”

–Jennifer Pastore

“If Invisible, I Visualize” will be screened for a final time from 6:30 p.m. on Friday, February 23.