Ayashii Art: Expressions of Beauty

From the late 19th century to the 1930s, the social image of womanhood in Japan evolved dynamically in multifarious stages, especially after the Meiji era. While the epitome of Japanese beauty has always been attributed to the feminine silhouette of the geisha, “Beauty” in its absolute essence has been interpreted in art not merely in the hallmark of physical charm, but also in the realm of the inner mind and soul. An alternate manifestation of beauty can be characterized as “decadent, bewitching, mystic and erotic;” therefore, translating into the artistic expression referred to as “ayashii.” In ordinary Japanese conversation, “ayashii” often connotes suspicion and doubt. In the ongoing exhibition “Ayashii: Decadent and Grotesque Images of Beauty in Modern Japanese Art” at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo until May 16th, the concept of “ayashii” is undraped as respect for the individuality, interest in inner elements of life, strangeness and mystery, monstrosity and mythology, superficiality, insanity, devotion, love and desire. The 160 paintings, prints, and magazine and book illustrations present an extraordinarily unique sense of beauty that may impart a “negative” mood, yet an irresistible presence at the same time.

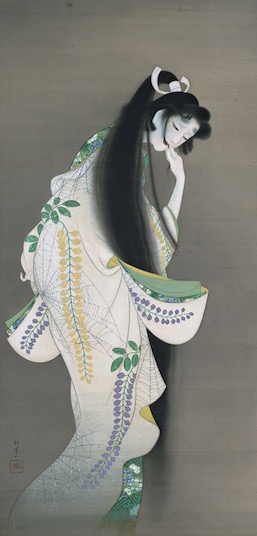

Two aspects of ayashii art are explained in the exhibition: discontinuity and continuity. Discontinuity refers to the works “affected by the change of eras,” and continuity “supports people’s sense of values” (Ayashii: Decadent and Grotesque Images of Beauty in Modern Japanese Art catalog). Shohaku Soga’s Beauty (Edo period, 18th century, Nara Prefectural Museum of Art), the oldest work in the exhibition, depicts a somewhat archaic representation of beauty and is said to have influenced Shoen Uemura’s Flame (1918, Tokyo National Museum), a manifestation of continuity. Both portrayals of women reveal similarities: Soga’s woman bites a letter, while Uemura’s bites her hair. However, their expressions of resentment and enmity vary. Black-tinted orchids on the kimono in Soga’s work contrast with Uemura’s use of white eyes on the Noh mask and the spiderweb-patterned kimono, which were symbols of jealousy and sorrow—these differences represent discontinuity. Further, the sensuous beauty of the woman in Flame is contradicted by the lifeless, chilling, “suspicious” look in her eyes. Uemura was widely known for imbuing emotion in her refined and delicate depictions of female beauty, a gesture of empowerment during a time when women’s rights and status in Japanese society were circumscribed.

Two aspects of ayashii art are explained in the exhibition: discontinuity and continuity. Discontinuity refers to the works “affected by the change of eras,” and continuity “supports people’s sense of values” (Ayashii: Decadent and Grotesque Images of Beauty in Modern Japanese Art catalog). Shohaku Soga’s Beauty (Edo period, 18th century, Nara Prefectural Museum of Art), the oldest work in the exhibition, depicts a somewhat archaic representation of beauty and is said to have influenced Shoen Uemura’s Flame (1918, Tokyo National Museum), a manifestation of continuity. Both portrayals of women reveal similarities: Soga’s woman bites a letter, while Uemura’s bites her hair. However, their expressions of resentment and enmity vary. Black-tinted orchids on the kimono in Soga’s work contrast with Uemura’s use of white eyes on the Noh mask and the spiderweb-patterned kimono, which were symbols of jealousy and sorrow—these differences represent discontinuity. Further, the sensuous beauty of the woman in Flame is contradicted by the lifeless, chilling, “suspicious” look in her eyes. Uemura was widely known for imbuing emotion in her refined and delicate depictions of female beauty, a gesture of empowerment during a time when women’s rights and status in Japanese society were circumscribed.

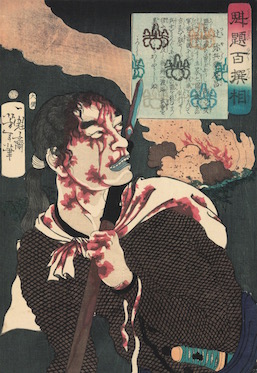

Monstrous or cruel expressions of the ayashii were also regarded as alluring, despite their eerie impressions. They are related to chimidoro-e, or “blood-covered” pictures, which feature gruesome impressions and an eccentric type of beauty that haunts and bewilders. An example is Yoshitoshi Tsukioka’s Tsuji Yahei Morimasa, from the series Selection of One Hundred Warriors in Battle (Kaidai Hyakusenso, 1868, Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts) (pictured above). In this painting to be exhibited from April 20, the artist has directed attention towards the subject’s look of agony and cry for empathy, rather than to the spine-chilling bloodstains on his face and scarf.

Themes from mythology and the Netherworld played vital roles in shaping ayashii expressions. Shigeru Aoki (1882-1911) was a prominent painter in the early 1900s who often combined Japanese myths, legends, and history with Western-style art. In his work Onamuchi-no-mikoto (1905, Artizon Museum, Ishibashi Foundation, Tokyo), he takes a scene from the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters) depicting a dying Onamuchi, who is restored to life by the goddesses Kisagai-hime and Umugi-hime. There are quite a number of works exhibiting mermaids, which are legendarily regarded as evil owing to their portrayal of seduction and temptation.

Another feature of ayashii expression is superficiality and “misemono” (show). During a turbulent period when people were threatened by peasant and urban revolts, earthquakes, floods, and epidemics, enjoying a show was a welcome remedy to battle anxiety and unrest. “Iki-ningyo” (lifelike dolls) became popular, such as the life-size mannequin on display, Princess Shirataki, by Yasumoto Kamehachi (c. 1895, Kiryu History and Culture Museum). In this mannequin, the exaggerated lip and nail color and over-highlighted white powder of the skin looked more “real” than the actual model. Tadaoto Kainosho”s Yokogushi (A Comb in the Side Hair, c. 1916, The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto) portrays a woman with an odd smile sealed across her lips, yet emanates a bewitching air, and was said to have been modeled after the Mona Lisa. Kainosho (1894-1978) was a Japanese-style painter from Kyoto famous for his decadent and sensual portrayals of female beauty, which were deemed peculiar in the Taisho period.

With regards to the Western influence on Japanese expressions of beauty, Romanticism emerged from the Meiji era, portraying human emotions and individuality. The magazine Seito (translated to “Bluestockings”), founded by Hiratsuka Raicho and published in 1911, challenged women’s roles in Japanese society. Illustrations such as Cover for Shojo Gaho, vol. 14, no. 8 by Kasho Takabatake (August 1925, Yayoi Museum) displayed the Japanese woman not in kimono but in Parisian attires and suggested their emotional and professional lives. The en vogue phrase “ero, guro, nansensu” (Erotic, Grotesque, Nonsense) spoke to “a person’s sexual beauty” with “unadorned appeal” and “satirical absurdity,” as well as expressions of love, devotion, and inner desires similar to the Western femme fatale (woman of destiny). These are visible in Tsunetomi Kitano’s Leaving All Behind (Lovers’ Suicide Pact) (c. 1913, Fukutomi Taro Collection), which exudes the sad expression of a couple who chose death in search of fulfillment. Kitano (1880–1947) was a Japanese painter and print artist who became one of Osaka’s foremost bijinga artists. Works by foreign artists Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) and Alphonse Mucha (1860-1939) also exemplify the Western influences on Japanese expressions of beauty. In sum, this exhibition expansively and brilliantly documents the multifaceted portrayals of beauty in Japanese art for over a century.

Alma Reyes

Alma Reyes