Interview with Tabaimo

The title of the exhibition Yoroyoron was coined by the artist from the Japanese words yoro yoro, which means to totter or stagger, and yoron, which means ‘public opinion.’ The word yoro yoro in the title is thus a reference to the “wobbly, ambiguous and inconclusive state” of her opinions. Society and ‘public opinion’ are not fixed entities, and recognising that she is a member of the general public and that by definition ‘public opinion’ encompasses her own, she expresses that sense of uncertainty in her work.

Featuring several large-scale installations as well as drawings, the exhibition design has made conscious use of the Hara Museum’s gallery space, something which visitors notice straight away with the work midnight sea (2006). If you go through the black curtains hanging next to the reception desk at the entrance to the museum, you will find yourself in a dark, narrow space, looking at the video work through a series of rectangular holes like letter-boxes. Wind blows in your face as the dark, animated sea appears before your eyes… The work can also be seen from a different vantage point on the stairs to the second floor.

Tabaimo, the set up of your installations often makes viewers watch your videos in specific ways. Is it important to you to control the viewer’s experience of the work?

It’s the same for all my works: it’s not so much about controlling the viewer’s point of view as it is about setting up a space which will encourage viewers to be proactive in how they look at the work. What interests me is the idea of setting up a space — be it narrow, dark, or on a slope — somewhere which is not easy to stand, somewhere which makes a variety of demands on how you approach it: basically an environment which denies you a comfortable viewing experience. I deliberately create those kinds of environments for the viewer to view the work in. That being the case, for some people, just the experience of being in this uncomfortable space is enough to make them give up on viewing the work, but there are other people who continue to look at the work in spite of the adverse conditions. It all depends on the viewers’ choice: I don’t just put the work in front of them and make it a comfortable experience for them – they need to be proactive in their viewing if they are to understand what I’m saying. I think the viewers’ stories themselves are the work, so by making the work together in a sense, by setting up spaces which cause the viewer discomfort — spaces which have elements in them that need to be overcome — the works become a participatory experience.

When I first came into the museum and saw this work, it wasn’t until I had walked through half of the exhibition that I realised midnight sea can be seen from two separate viewing points. From the first, you can’t see the sea clearly, it’s as though the world has been inverted…

That’s right, you’re looking at the work from its side, so it’s completely different from the upstairs view: the moving lines only come into view gradually. From downstairs, it’s much more important that they are interested in what the work depicts than whether they can see it properly or not. But it’s fine if some people go home without realising that the work can be seen from more than one location.

I felt quite a strong sense of paradox when I was looking at the work through those peepholes: while the act of looking at this sea was an abstract experience, the feeling of wind blowing on my face made it feel like I really was by the sea. Was this paradox something you set out to achieve?

No, no (laughs), really, it’s the same every time I make an installation: something completely coincidental happens and if that coincidence doesn’t look like it was something conceived as part of the work from the beginning, then the work is no good. So in this case, the wind in that space is completely coincidental.

There are no fans? How come there’s a wind blowing?

It’s the air conditioning: there’s a jar-like thing above it which moves and the air rushes out of it. There’s not very much space for the air to escape, so it picks up speed, that’s all. I didn’t take that into account at first, but that coincidence has had a big, positive effect on the work.

In midnight sea, there is this strange hair-like, wig-like form which moves through the sea like a jellyfish or something. You’ve said that this work plays on the Japanese words for ‘hair’ and ‘spell/curse’ [both pronounced kami no ke in Japanese]. Wigs and long hair have certain connotations for Japanese people, don’t they.

There are probably people who only see women’s long, straight hair as exactly that, ‘hair,’ but I think that recently the way horror films portray hair, or dolls which have hair growing even though they shouldn’t be alive, has produced quite a fixed impression of it in people’s minds. I didn’t set out to make use of that impression; the original starting point for this work was more the idea of viewing the movement of a human figure from above. There’s the body, and the hair, which seen from above move along like this. When I thought about it, I decided I didn’t need to portray the body: I felt it was getting in the way of creating a strong, clean image and so I got rid of it.

As for wigs… Since a long time ago there have been wigs made with real human hair, from which you can extract DNA, and I think that’s something that pretty much everyone finds creepy. But when I made the work, I was simply thinking of it as a human form seen from above and how it might look like some kind of new animal if seen moving through the water; the tip of the hair moves like a fish’s tail. I used hair as a material but it was only after doing so that I discovered its essence and how it connects to the other concepts in my work. I take parts of different things and put them together to produce my work; I can’t make anything knowing exactly what components need to be used from the beginning.

The alteration or obliteration of the human body is a theme that recurs throughout your work: for example, your drawings of distorted hands intertwined with the bodies of insects or the image of a baby being born out of a woman’s nose. Do you have any particular thoughts about the human body?

I think that animation is a very important form of expression, but in order to show something in animated form, you have to get rid of all excess features or else you will often find yourself unable to express what you’re aiming for. So I get rid of all the things I think are unnecessary in the images and… for example, babies are normally born from between a woman’s legs, but I didn’t feel it necessary to express that in the animation. Everybody already knows how babies are born, so I thought that if I portrayed it in a different way, perhaps I could imbue it with a different meaning, that perhaps it’s possible to express a deeper insight into something in only an instant. I think the human body is particularly open to those possibilities. We are used to seeing our hands attached here on the ends of our arms, and at this age we all know that babies grow in the womb and are either born by Caesarian section or from between the legs, so I think by subverting those preconceptions, it makes it possible for viewers to ask why things are the way they are, and search for the answer to that question. So I don’t feel it necessary to portray the world as it really is.

Japanese Kitchen (1999), made for her graduation exhibition at art school, was the work that established Tabaimo’s reputation. It shows the familiar, domestic scene of a housewife cooking in the kitchen, but the atmosphere is one of unease and there are a number of incongruous, unsettling images and messages that appear throughout the work: a politician campaigning inside a microwave, an old woman chanting in a jar and a salaryman at his desk in a fridge. To see the work, viewers have to enter a narrow, wooden structure with tatami mats and paper screens, which feature the design of the Japanese flag. The social themes are clear to see in Tabaimo’s work, so I was interested to find out if there is also a political undercurrent to her work.

With an object as distinctive as the Japanese flag, which you have used in Japanese Kitchen, was there something specific about it that you had in mind when you made that work?

When I was making that work, the law concerning the national flag and anthem was passed, and it was quite a controversial issue. I don’t have such strong feelings about the flag, but I really admire the simplicity of its design, the way it expresses Japan with that single red sun. People have assigned all sorts of meanings to that design even though our generation has not experienced these things. But when I think about what it means to my generation, it doesn’t particularly conjure up images of the things we haven’t been involved in, like the war or the fanaticism surrounding the emperor.

Whatever we feel about the flag is not what we’ve experienced but in a sense what we’ve had drummed into us by our grandparents’ and our parents’ generations; it’s information taken from experiences we haven’t had and then projected back onto the flag. So I think that that kind of information which we have not experienced for ourselves is merely information, and that we have to believe in and express what we feel now. My work is not about what we have experienced up until now, or things to do with the war — I’ve only been alive for the past thirty years, and that’s what I’m concentrating on.

But in this work you’ve depicted a politician inside a microwave. Does that have any connection to the flag?

The politician and the flag are both the same symbol. For me, I don’t just want to accept the political nuances that are embedded in the flag. The flag really isn’t something that people should feel reverential towards. Unless people are conscious of the fact that the flag is simply a sign, when they see it they think of the right wing, right? I don’t think it’s good at all that the flag makes people think of the right wing, and something should be done about the ongoing use of the flag as a symbol of the right wing. So when I think about how I feel about it all now, I think that it’s important for people to express precisely what their thoughts are about the flag. When people start to express different ideas, there will be conflicts in opinion and that will lead people to think more.

My works Japanese Kitchen and Japanese Zebra Crossing both feature the flag and I’ve often been asked about whether that has any great meaning to it, but there isn’t: my repetitive use of that motif is my sincere attempt at responding to the flag and by repeating my use of it maybe people will eventually understand what I am trying to convey. I think it’s important to convey the message that the flag is not so important: it’s just a symbol.

I felt that the installation of Japanese Kitchen itself felt like a temple or a shrine. Is that something you intended?

That’s a coincidence. When it comes to space, I make my work thinking about how to achieve the greatest effect in the smallest possible space… and I was thinking about making it as symmetrical as possible.

Or rather than a temple or a shrine, perhaps it’s more that the installation resembles a stage…

The concept of my work being like a stage wasn’t something I thought about at first, but recently I did a collaborative work with a dance company and I realised that what those people are doing has similarities to what I am doing. Until then I really wasn’t aware of it; it’s only recently that I realised.

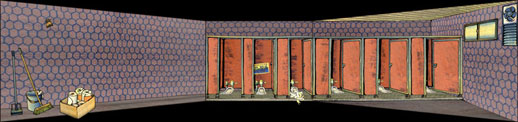

The stage-like feel to her work is felt in public conVENience (2006), where again bizarre actions take place in a familiar setting: a woman repeatedly tries to flush a turtle down the toilet; writing appears by itself on the cubicle walls; another woman stands in her underwear in front of a mirror, and most sinister of all, a moth with camera shutters for eyes comes in and photographs her.

The title of this work is another play on words: in Japanese koshu benjo, meaning ‘public toilet,’ is normally written “公衆便所”, but Tabaimo has written is as “公衆便女”. The characters “便所” literally signify ‘excrement place,’ but in her title, “便女” (a made up word that is also pronounced benjo) the characters mean ‘excrement woman.’ There is no easy play on words that can be made between the words ‘toilet’ and ‘woman’ in English, so instead she focused on the Japanese pun to be found in the word convenience, in which the sound ven sounds the same to a Japanese person as ben (便 – ‘excrement’).

When I saw the Japanese title of this work before coming to the exhibition, I was expecting a work dealing with misogyny or women’s issues.

No, it’s not. It’s more about the space, so that’s why I chose to use a women’s toilet. I’ve only experienced women’s toilets, so I can picture what takes place in them, what kind of spaces they are. Women do a whole range of things in there — it’s interesting.

The image of the baby being born out of a woman’s nose and disappearing off down the toilet with the turtle is so strange. What does it mean?

This time I’m using the tortoise in a different way from previous works… do you know the story of Taro Urashima?

For non-Japanese readers who are not familiar with this story, here is the basic outline. There are various versions, but essentially the story tells of Taro Urashima, a fisherman who was walking by the sea one day when he finds some children bullying a turtle. He makes them stop, and as a gesture of thanks the turtle takes him to Ryugu-jo, the Dragon Palace under the sea. He rides on the turtle’s back and arrives at the palace where everyone welcomes him with wonderful feasts and parties; he spends a while there but becomes homesick and asks to be allowed home. The queen of the palace gives him a jewel-encrusted box as a gift but tells him never to open it. When he gets back to the real world he finds that 300 years have gone by and nobody remembers him any more. Depressed, he goes to the beach, remembers the box and opens it. A white cloud is released and he suddenly ages and dies, as the box contained his true age.

The turtle is taken from this story, in which it represents various things, but I guess nobody will ever know if Urashima was happy in his life or not. That turtle — which was at first being bullied then disappears down the toilet with the baby on its back — probably takes the baby out of good will but nobody knows whether the baby is happy or not. But we also don’t know if the baby would have been happy being brought up by a mother who was willing to flush it down the toilet. I think people would not think about the issue of the baby’s happiness regardless of whether they know the story or not.

In previous works I used the turtle as a symbol of men. So in this work, while it looks exactly the same, I’m using it in a different way.

Yes, it could be interpreted as representing the frustrated salaryman, right?

There’s a scene in one of my past works in which salarymen turn into turtles one by one… but while this time round I think of the turtle as the turtle from Taro Urashima’s story, it’s fine if it’s not looked at that way. When I was making the work, Urashima’s turtle was an important element to me, but now that the work is completed I leave it open to various interpretations. I’m interested in what those interpretations are and I make new discoveries particularly when talking about things in interviews.

And how about the moth? It behaves in a very invasive way.

Moths are not all that different from butterflies, but they really creep people out, don’t they. I gave the moth camera shutters for eyes, partly to imply the illicit photography that happens in toilets and partly to suggest various people looking in and as that moth flies out of the window after taking photographs, you don’t know what becomes of those images.

Nowadays, people appear on the internet and in other media for all sorts of reasons, but the things people are talking about were, until the internet age, just features of everyday life, things that nobody used to talk about — it’s the internet which has given a voice to all this, right? For example, it’s possible that I’m also being talked about on the internet. On the internet, anyone can become the ‘main character’ as it were, but that’s not to say it’s in a good way: they might be the victim of libel, or have had illicit photographs of them taken and published online where anyone can see them. There isn’t much you can tell from a single photograph, but people say whatever comes into their heads, although that can also work in positive ways. For example, I set up this exhibition, the information spread and people who have come to see it have sometimes written about it and promoted it. There are pros and cons with the internet, and there are pluses and minuses associated with the existence of that moth, so it’s not a case of trying to say whether it’s god or bad. I think of it as a purely unnerving presence in the work. Even I don’t know what becomes of it after it flies out of the window. On the internet, even though you become the centre of the story, you don’t exist in the space where the story is taking place. And that’s where it’s unnerving.

How do you feel about the media in general? For example, in Japanese Kitchen you can hear a weather report on the radio saying “it will rain junior high school students today,” which is a bizarre twist on the relationship between the media and reality. Your work deals with some of the social problems in Japanese society and the media here tries to address these issues, but in my view tends to do so quite superficially. What do you think?

For me it’s just a motif. It’s one of the ‘mirrors’ through which I try to figure out how I feel about the events that take place in our society. So it’s not the events themselves that matter so much as how I receive and respond to that information and how I believe it: the media just makes me think about these things. Through that, I can get to know myself. So it’s just a motif for finding out my true thoughts and the feelings which are true to myself. And it’s the same while I am making the work: when it’s done, I become the viewer and as a when I see the work as a viewer I become able to answer some of these questions for myself. So I don’t have any specific opinion of the media that I am trying to express, but because I’m addressing social problems in my work, it’s difficult to get people to understand what I am trying to say. To me, my work isn’t social criticism, and that’s what I have to explain to people.

The internet offers a medium by which anybody can express what they want to say. How do you feel the differences between those two realms of expression?

I think that anyone can be a force of expression, and of course, it is possible to achieve that on the internet. For me, it’s not that I don’t believe in the possibilities on offer on the internet, but rather that I’m not that interested in it, so I don’t particularly feel the desire to participate in it. So, while I don’t have a homepage, perhaps other creators who look at things differently from me see the internet as a place full of potential. It’s very convenient that people can look at artworks from the comfort of their own home, and are able to get information off the internet — if used to its full potential it could be interesting, but I wonder what it means for the viewers. It’s difficult for the web to make people feel proactive, to bring out the proactivity in them. But the people who do believe in it are working hard at what they do, and as I believe in the potential of the art gallery as an axis: the gallery and the internet are two axes, each progressing in turn. Art is making compromises on the internet, and is being evaluated in a different ways. Within that, absolutely everyone has the opportunity for expression, don’t you think? You can use the internet or you can open your room up as a gallery, and that’s something I find interesting. So there are all sorts of possibilities, but I still believe in the potential in museums and galleries.

Tabaimo, thank you for giving us so much of your time. This is a fascinating exhibition and it has been intriguing to hear what your intentions behind the works are. We look forward to seeing how your work develops from hereon.

(Translation: Ashley Rawlings)

Ashley Rawlings

Ashley Rawlings