Is there a Future for our Past?

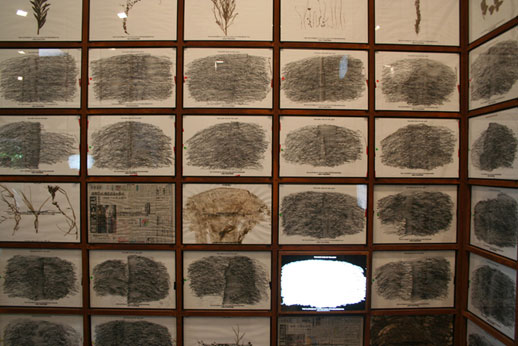

The Japanese Pavilion at the Venice Biennale this year has been covered from floor to ceiling by 1,400 frottages and pressed flowers, collected over a period of 9 years from the Ujina railway station in Hiroshima, which retained the traces of the atomic bomb explosion but was removed in 2004 so as to make space for the construction of a new road. In this interview, artist Masao Okabe and commissioner Chihiro Minato discuss the issues behind the exhibition.

First of all, I’d like to ask you about the title of this exhibition. One of the defining characteristics of the current times is that something like the ‘apocalypse’ can be imagined easily and in various ways: global warming, destruction of nature, dramatic population growth to name but a few. In other words we are experiencing a “crisis of the future”. This exhibition however focuses on the past and the possibility of taking this past into the future. Can you tell us about what made you choose this title, especially in relation to the current socio-political situation?

Minato: This title is formed of two sentences. The first one, “Is there a future for our past?” was the title we used when our proposal was chosen from the 4 proposals that were in the competition to exhibit in the Japanese pavilion. The second one, “The dark face of the light” is the title of Mr. Okabe’s series of works that have been exhibited. Both sentences are somehow paradoxical in that they include contrary concepts within them through the juxtaposition of “past and future” and “light and dark”. Put simply, the reason why I chose this title is that science, which is one of the ultimate causes for the various catastrophes that have occurred since the year 2000 – or even before as we seen for example in Chernobyl – has reached a critical point that gives us human beings two different types of future. One is a bright future. In other words it is the concept born in the 18th century Enlightenment and still accompanies us: a future in which a better, longer and healthier life is possible. The second one is a contrastingly dark future characterised by decay, environmental destruction, problems relating to radioactivity, and so on. I believe that the contemporary man holds those two contradictory futures. The same phenomenon happens to our past. An increasing number of pasts are being discovered and shared by an increasing number of people.

I believe Venice is symbolic of what we’re discussing here. There are not many cities in the world where such a rich past has been conserved. At the same time however, Baghdad, which has a history that goes back to Mesopotamian civilisation, experiences fierce destruction and one of its museums that conserved the first letters in human history was plundered.

Two contrasting processes are occurring simultaneously. We can therefore say that when our future is in danger, our past is also in danger. This brings us to the second title. The light that we see is actually sustained by a darkness that is as dark as the light is bright. I encountered Mr. Okabe’s works 6 years ago and I remember being deeply fascinated by the title, which I didn’t fully understand at the time. By slowly discovering Mr. Okabe’s endeavors in Hiroshima however, I came to realise that he was actually transferring the past in its full duality onto paper and this became the theme for our exhibition.

In the opening speech yesterday Mr. Minato talked about the duality of the past also in terms of the gap between personal and social time, pointing out that Mr. Okabe’s activities can be understood as an attempt to reduce or fill in this gap. Mr. Okabe, what is your understanding and relationship to this duality of the past?

Okabe: I have been using frottage as an expressive technique for over 30 years now. Frottage is not a new technique at all and only requires a pencil and a piece of paper which is placed onto the fabric of the city or the road to make an impression of the “expression of the present”. It is a technique that allows one to obtain a vast imagination through sensing the irregularity of a surface with one’s own hands. I believe it has an almost primordial character in comparison to printing or other media that are subject to the continuous and accelerating development of technology.

The initial reason I started placing pieces of paper onto the surface of the city was the need to understand where my present was located and I therefore started by making frottage impressions of literally where I was standing. It was a verification of my own identity. The first thing I noticed was that the surface of the present which lay just beneath the surface of the paper emerged onto the paper. This is not such an obvious phenomenon and I felt a definite sense of wonder at the fact that a material was revealing itself through another material, which encouraged me to continue in this activity. After a while, I began to be fascinated by the expression of the city and what lay deeper beneath it. I began to perceive the changes in expression within a single surface over time, and different expressions began to recall different events. This led me to perceive the present as a condition where the numerous layers of the past were piled up on top of each other, or rather I began to be able to feel those layers emerging onto the surface with my own hands. This is after hundreds of frottages. This induces a peculiar feeling, one begins to make impressions of not just the surface of the present but also simultaneously that of a past present and an even older present. This all gets incorporated onto the membrane of paper. On the other hand, the paper also records one’s own activities on the paper. The strokes of the hand which try to contain the shapes beneath the paper are captured by the paper, as if one’s own present is being captured. I was told yesterday that it is rather like moulting…

In what sense?

Okabe: like cast-off skin. You are being copied while trying to copy a surface. So the traces of a city and the traces of one’s own strokes are brought together on a thin sheet of paper.

You could say that the time of the city and the your personal time are merged together.

Okabe: Yes and the present immediately becomes the past while moving forward. I don’t know if I can call it the past in its true sense, but through working on those frottage impressions I definitely became aware of ideas of time, or the accumulation of time. You could even call it history.

The comparison that Mr. Okabe just mentioned, moulting, has a strong connotation of physicality and I believe it directly connects with the physicality of his work. Was there an intent on your part to make a statement against the digital as opposed to physicality?

Minato: There was no intention to do so but it might be an interesting view point to take. Whether it be cameras or video cameras, digital apparatuses record by converting information into signals and save them in the form of quanta. I think it can be said that Mr. Okabe converts information through his body. A crucial difference with the digital process is that the saved quanta can be easily modified later on: Photoshop is an obvious example. Mr. Okabe’s works on the other hand, present the singularity of an action: once something is set on paper it can no longer move.

Another issue that I’m recently interested in is the concept of resolution. We’re currently living in a resolution myth where a higher resolution is believed to be inherently better. This is however an extremely superficial technical understanding and it fails to understand what I believe is the truly best resolution, in other words the resolution which is most suited for recording reality. A truly high quality resolution should be understood in terms of how well a particular reality is anchored or preserved. Frottage is at first sight a simple technique but it actually presents a highly complex process especially from an epistemological point of view. I believe it would be interesting to attempt a reconsideration of our current image environment based on frottage.

That reminds me of a passage in your book Chu-shisha no Nikki (Diary of an Observer) even though that was referring to virtual reality and not images. When asked by a philosopher what we would lose if we were to obtain a perfect representation of reality, your answer was that all possible ramifications of the future would be lost and therefore human beings would stop walking, and life would lose its meaning. Maybe we could say that frottage contrastingly creates or provides space for life.

Minato: I think so. Mr. Okabe always mentions the fact that the place where one is standing right then can be the place of creation. There is infinite extra space if one takes one step. Or even at the exact same spot a future is constantly born. I think that is one of the reasons that Mr. Okabe has continued to work on the same stone for 9 years. The exact same place has a different skin just beneath the surface skin.

As people enter the exhibition, they are overwhelmed by the amassment of time – both personal and that of the city – but Mr. Okabe also actively involves others in his projects that incorporate other people’s times. For example in the aerogram project you send frottage impressions to others by post and you are also active in organising workshops, as you have done here in Venice. Could you talk about this inclusion of other people into your projects?

Okabe: First of all the simplicity of the technique enables people to express themselves. I believe that art can be a viable method to attempt to look at the city, to gaze under one’s own feet, as I have been doing. I am not trying to didactically force people to do the same as I do, but instead I believe that by using art as a means to view a place where one lives and its environment or its history, other new perspectives can be discovered. I think that my workshops and collaborations ultimately lead to the presentation of a new perspective, a new way to look at the city.

The next question is rather general but leads on from this “social” aspect of Mr. Okabe’s works and it concerns the relationship between art and politics. Do you think art in this current context should include a political element?

Minato: I think that is dependent on the understanding of the term politics. For example, in terms of actual politics, in other words the kind of politics you for example see at the Arsenale, the decision of whether a political element is necessary or not lies on each individual artist. However if we go back to the origin of the term politics, which is to say politics born in the Greek era, not only art but any attempt at producing an object inherently comprises politics; you could even say it is a precondition. The word ‘polis’ indicates the engendering of shared values amongst people living in cities. Therefore for human beings who are faced with various potential forms of destruction and ‘ends’ as you mentioned before, a condition for producing objects should be the endeavour for creating shared values. I believe that is the kind of political element we should be discussing.

Okabe: Yes, I think one of the motivations that led me to continue in an artistic endeavour was a presentiment that I could unearth subjects of value within oneself and within places and particular times.

It is probably too early to ask you this since the exhibition is not even open to the public yet but you brought Hiroshima to Venice and I’d be interested to hear your reactions about the impact that the exhibition and workshops have had, especially at the personal level.

Okabe: I often reflect on different times: 1945 as the beginning of Hiroshima, 1942 as the year I was born, 1996 as the year that I started working at the Ujina station, 1986 as the year I started being involved in Hiroshima. Every time I go to Hiroshima I feel my personal time and that of Hiroshima. I believe Hiroshima is a particularly important subject for human beings and that is why it triggers such sentiments of depth and enormity. I cannot compare myself to such a subject but I do want to understand my time in terms of a simultaneous progression with that of Hiroshima. I therefore don’t want to solely focus on Hiroshima but rather the relationship between myself and Hiroshima. Thinking about Hiroshima is equivalent to thinking about my own life. And I think that the same can be said about the people who take part in my workshops and I hope this will create new connections. It is the depth that Hiroshima encompasses that enables numerous subjects to connect both at the personal and social level. Mr. Minato mentioned this earlier but my activities are attempts to pull the past into the present and solidify as a work so that it can be passed onto the next generation. I believe that is art. Venice is a city that has been centre of exchange since antiquity and I think it is an ideal place for such a conversation to occur. And if that conversation is engendered by a subject which i have been working on there, then definitely there was value in bringing Hiroshima to Venice.

Minato: As I walked around Venice I realised it shares a few aspects with Hiroshima despite the fact that the two cities are completely different. First of all, they both face onto an inland sea: Venice opens onto the Adriatic Sea, and Hiroshima opens to the Seto Inland Sea. Cities with an inland sea have certain similarities. Secondly they both have a tradition of military navigation. Hiroshima of course has the Ujina port, but Venice also had a shipyard called Arsenale and still today contains a military zone that is off-limits to all citizens and even vaporettos. So there continues to be an extremely difficult reality where one seventh of the city is owned exclusively by the military. Presenting art in this context is a statement of protest. While we were trying to decide the first location to hold a workshop, the teaching staff at the University Institute of Architecture suggested that we do it at the Arsenale. The workshop went well with over 30 city residents taking part but there was one comment that particularly struck me which was that despite walking past the place very often it was the first time that they actually interacted with it and really felt it. That made me think that there was sense in bringing the project from Hiroshima to Venice. It might have been a modest one but it still was an action. And I hope that all the participants, from children to renowned scholars will take their frottage impressions home and inspire new conversations that will slowly expand and connect with others.

Thank you very much.

Naoki Matsuyama

Naoki Matsuyama