Here Lies at Rest: The Material Culture of Death

Polina Davydenko After Time 2024

From May 2025 until August 2025, I was in residence at Arts Initiative Tokyo to conduct research on modes in which grief can persist over time. Over the past years, I have dedicated my research to better understanding how grief manifests itself and behaves within societies that are heavily influenced by neoliberalism and capitalism. They respectively cause the privatisation of grief and push for efficiency when it comes to the time we have for grieving. I found that both these tendencies put pressure on grief that is unhealthy and further complicates our relationship with a topic that has already been pushed to the margins in neoliberal and capitalist society.

Neoliberalism, on the one hand, causes grief to go underground. The emphasis on the individual that came with the rise of neoliberalism puts grief at risk of privatization and stigmatization, pushing it outside of shared life and limiting it to the private spheres of the home.

Capitalism, on the other hand, with its pursuit of efficiency, lowers the time available for grief. In capitalism, we are all made to be producers and consumers in order to uphold the system. In Oppression of the Bereaved (*1), Dr. Darcy Harris describes how grieving individuals consume way less market goods, which threatens the capitalist system. So we are pressured to return to our ‘normal’ lives as producers and consumers as quickly as possible, limiting the time for grief.

The limitation of consumerism by grieving individuals, however, has been quickly recognised as a gap to be filled; as an opportunity rather than a threat. We can see an adaptation through goods and products that are specifically targeted towards this group. With these goods, grief is turned into something that can be benefited from, turning death into a commodity. There are many examples of this: commodification of death care, commodification of the body, and, maybe most clearly, through the commodification of death rituals. In Japan, I encountered a very striking example of this, through corporate graves, something that, as far as I understand, is unique to the Okunoin cemetery in Mount Koya.

On the lane leading up to the main temple where the mausoleum of Kobo Daishi is located, you can find corporate graves; Yakult, Nissan, CCA Coffee, for example, have graves said to offer a place for their founders or employees to bury their ashes. Striking to these is their contrast to the other surrounding graves. In general, the graves I have seen in Japan are made from natural stone, with the focal point of a singular or a few pillars. Engraved on them is the family name to which the grave belongs. However, the company graves differ from these. Visually, they are closer to the company’s identity through the use of sculptures and even color. They, therefore, exceed their purpose of being merely a grave. Their visual language and their placement, mainly around the main lane of Okunoin Cemetery, both contribute to their character of almost becoming an advertisement for the company rather than a grave. Here, we can see one of many ways in which death becomes a commodity through the capitalist system.

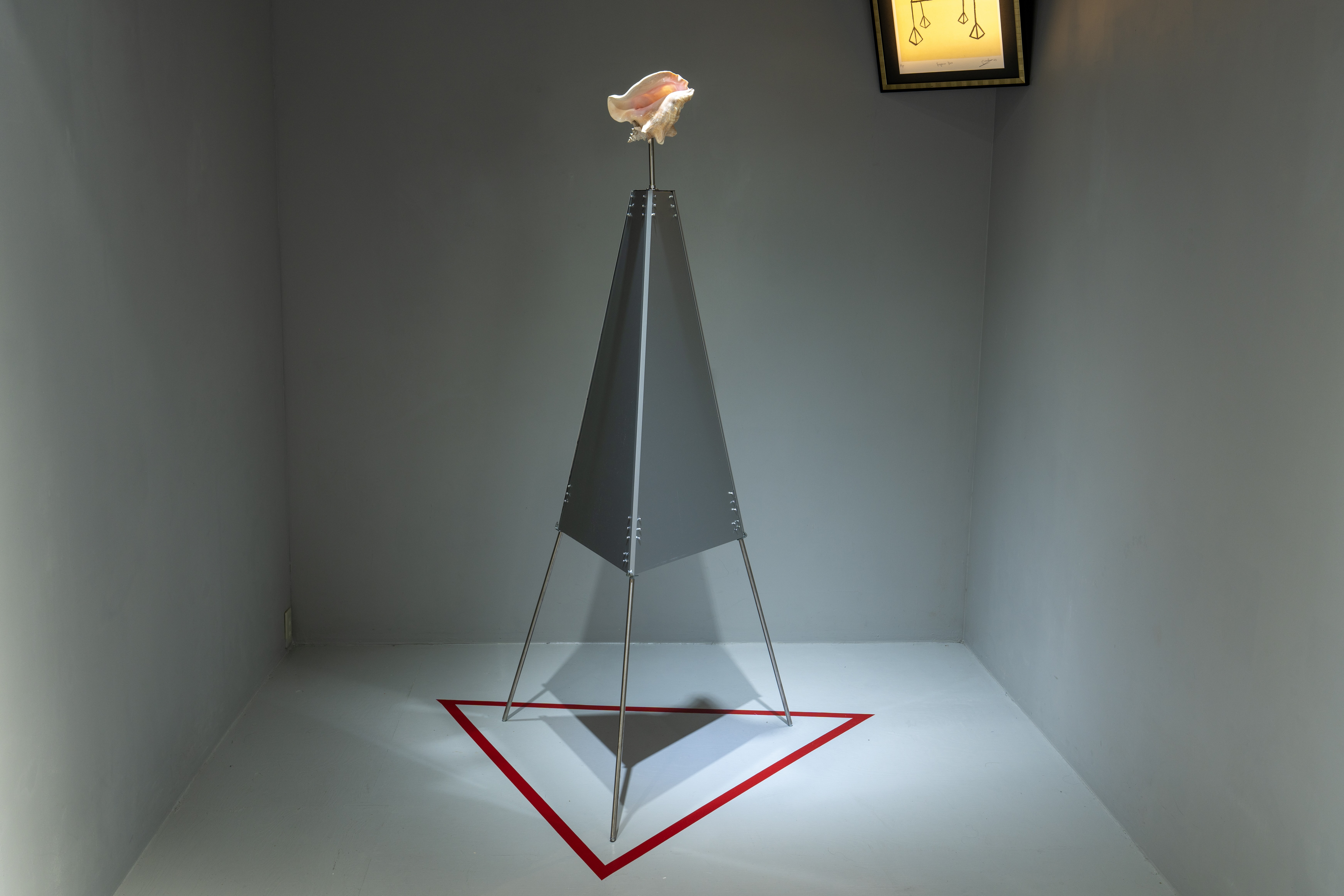

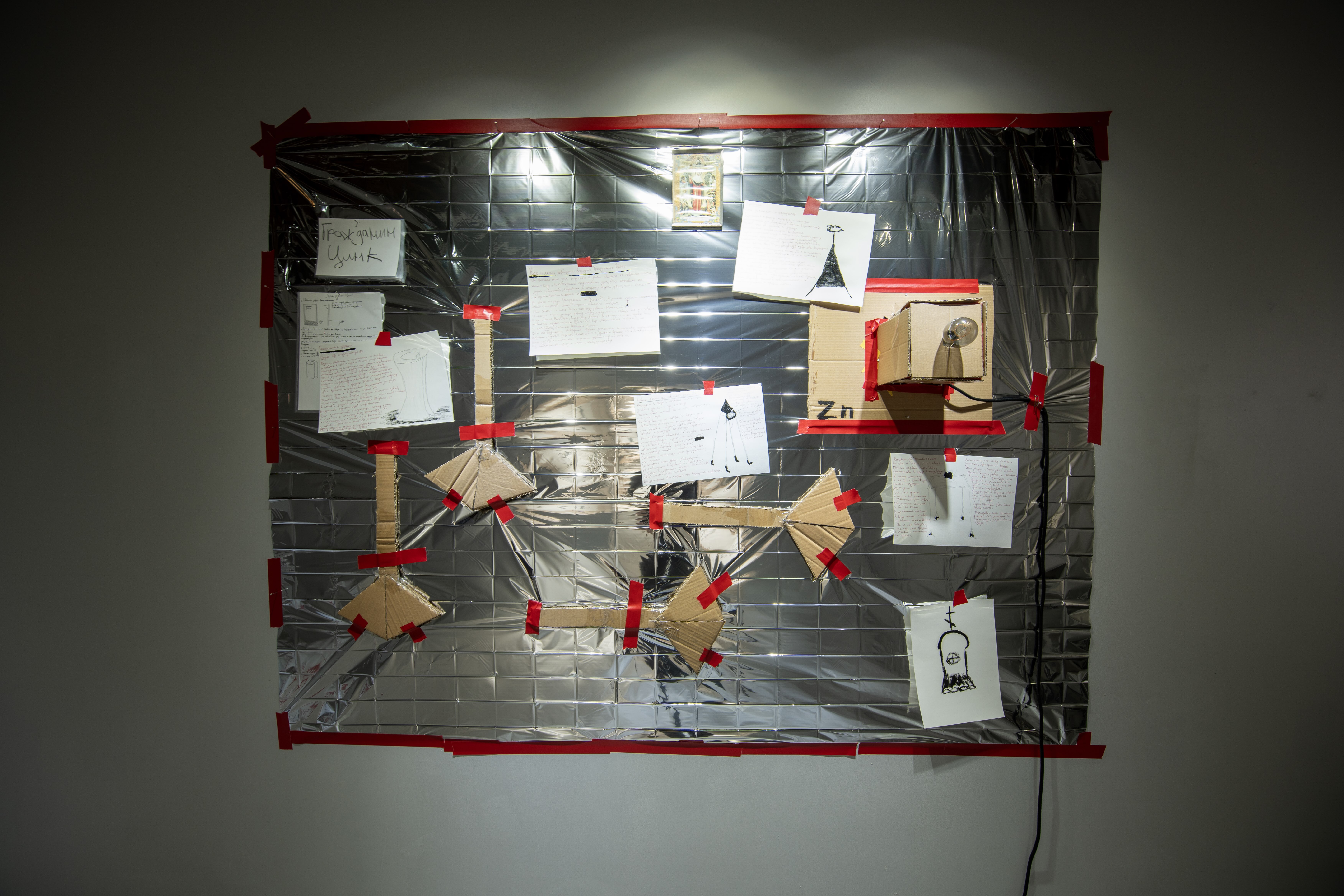

Artist Marko Kolomytskyi speculates about a world where death can exist outside of capitalism: “Capitalism is death. Modern society glorifies death. It exploits the living and forgets the dead. It must be dismantled” (*2). Are the words received to an ‘antenna’ and heard in his solo exhibition From Donbas to the Cosmos (2025) at Decameron in Kabukicho. Death and grief play a central role in Kolomytskyi’s work and life. It has been for a longer period of time, but was intensified and made more explicit after the death of his mother a few years ago. The artist has now devoted his practice to his own interpretation of Russian Cosmism. Perhaps rooted in hope, perhaps rooted in grief or despair, the artist pursues modes of becoming immortal as well as the material resurrection of the dead. Departing from a critical ens towards today’s society, Kolomytskyi’s proposal combines Russian Cosmism with anti-capitalist practice and contemporary science.

If we want to succeed in the objective Kolomytskyi strives forーthe resurrection and materialisation of the departed without subjecting ourselves to the vortex of exploitation and commodification of our bodies and beingsーwe need to find a way to do so outside of capitalism. Capitalism sketches human finitude as a problem that one has to overcome by self-optimization to the extent of immortality. In doing so, commodification of the body, continuous labor, exploitation, and consumerism can continue; all habits that are pursued by capitalism. So if we want to strive for immortality detached from these terms, we need to kill capitalism first.

Not only the materialisation of the deceased, but also sites of memorials that are built to commemorate them, offer a place of defiance to the aspects that shroud death in the world of the recent past and today. Through these memorials, we might take a stance against the limited time that is reserved for grief, while reclaiming space for grief in public spaces. It is this act that holds the potential to make grief both enduring and shared, directly contradicting the forces put on grief by capitalism and neoliberalism. These objects of material culture make death and grief an inherent part of societyーthey refuse the denial of grief through their physicality, through their occupation of space within the city, as if they were part of a silent protest against death-denial. On the plaque of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, we can read the objective of the site:

“In order to have this tragic fact known to succeeding generations and to make it a lesson for humankind, the reinforcement work of the ruins has been done by the contributions of many people who desire peace within and out of the country. The ruins shall be preserved forever.”

It is through the visual scars and marks of destruction caused by the nuclear bombing from exactly 80 years ago that the immaterial damage is commemorated, taking shape through the ruins of the building that was so close to the explosion of the bomb.

Similarly, we can see the destructive effect that the tsunami of the Great East Japan Earthquake had on Ukedo Elementary School in Namie Town, Fukushima Prefecture. Within the school, visitors can see the damage done by the natural disaster. The waterline left an imprint on the wall of the upper floor, on the lower floor, almost all furniture has been washed away, and in the former gym, the floorboards and walls have been demolished by the earthquakes and the following tsunami. For the preservation of these sites of memorial, there was a choice made not to repair something that is beyond fixing, but rather to lay bare the losses that were suffered. Through the material, we can come close to the disasters that have happened here, and we can feel the loss and sadness that still echoes through these places. Through the conservation of these buildings in their state of destruction, generations to come can be educated on what took place here, offering a place for commemoration of the dead and for sharing grief.

By encapsulating grief in stone or other materials that endure time, the seeming expiration date of sorrow and grief gets sidelined. Not only can we find these examples within architectural modes, but we can also recognize the refusal to submit to the lack of time for grief in art. I feel that the work After Time (2024) by Polina Davydenko is a beautiful intersection of memorial sculpture and contemporary art, exemplifying how material culture can hold stories of loss and grief that can long outlive us. In the film, we see six stone sculptures in a changing environment. They are located in a field, but soon this changes to a landscape filled with snow, then a hurlwind of flames follows. The sculptures, or so-called ‘babbas’, are personifications of ancestors that were crafted to help the deceased cross from the world of the living to the land of the dead. The sculptures can be found in Izium, a city in Ukraine. Against a backdrop of the changing seasons, Davydenko exemplifies the ongoing wait for a war that is seemingly never-ending. It points to the persistence of grief, how it can stick with us over the passing of time, through the seasons of our lives. The war has brought a lot of destruction and loss to Davydenko’s country. These baba’sーstone sculpturesーact like silent observers of this. Their materiality ensures their long-lasting presence in this world; however, their existence is also not guaranteed.

In my interview with Flash Art, I described the following: “It shows the steadfastness of these objects of cultural heritage through a material as everlasting as stone. But even this material can be harmed, as we see here [during the Russian war on Ukraine] by human violence. It is through Polina’s film that another layer of resistance of time and resistance of physical harm get added, After Time ensures the survival of the babas in a different medium" (*3).

The receptiveness of material to man, or nature-made manipulation, can assist us in grieving. Whether it is by force of nature, by destruction, by human aggression, or by intended craft, these objects can become a site of memorialisation within the public or shared space. In the examples discussed above, they usually embody a shared or national loss, but these sites of memorial can just as well be found for individual cases of loss. Through the embodiment of pain, sorrow, loss, and grief, these objects can become catalysts for the practice or discussion of grief within our societies and communities. Their perseverance over time additionally ensures that these discussions and practices become intergenerational while they simultaneously defy the lack of time reserved for grief under capitalism.

In the face of capitalism, we need to seek both these existing and imagined practices for collective and shared grieving. The material culture of death and grief is merely one example that examines the potential to reclaim grief within the commons. I dare you to find the gaps that have not been filled yet and seek ways to commemorate the death, to dwell in sadness, and to welcome grief as an inherent part of life, but above all, I dare you to share these with both friend and stranger.

*1──Harris, D. (2010). Oppression of the Bereaved: A Critical Analysis of Grief in Western Society. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 60(3), 241-253. https://doi.org/10.2190/OM.60.3.c

*2──Kolomytskyi, M. (2025). Antenna [Sculpture].

*3──Sýsová, A.(2025, December). Against the Privatization of Grief; Conversation with Dutch Curator Julia Fidder. Flash Art Czech and Slovak edition, 78, 43-45.

Julia Fidder

Julia Fidder