Mazes that Lead Nowhere

Although planned prior to Bruce Conner’s death earlier this year, Miyake Fine Art’s diverse exhibit of this American West Coast artist’s work coincides in a timely fashion as the art world looks back over the five decades of his career.

Born and educated in the mid-eastern United States, Conner’s work rose to prominence in 1956 first a solo exhibition in NYC at the Rienzi Gallery, followed by two in San Francisco in 1958 at the Designers Gallery and East West Gallery, following his relocation there in 1957. Works on canvas, made with both paint and his more characteristic mixed-media “assemblage” pieces were shown in San Francisco. Incorporating found items from the city, these works were imbued with new significance and their collage-like compositions echoed the city’s urban decay and consumerism’s waste.

With his short film A Movie (1958), Conner made a name for himself on a larger scale helping to form his current image as a multimedia artist. Filled with images of animals and accidents the film is composed entirely of found footage that has been interpreted as a metaphor for humanity’s violent nature. In a similar sense, his work on display at Miyake Fine Arts seems composed more by a brilliant editor as the work’s expressive content originates from the juxtaposition of the constituent found items, bits of discarded consumer goods or photos and the different possible origins of those items than a direct and singular subject. The compositions express meaning in ways similar to montage; the convergence of two disparate elements produces something more powerful and unique than each alone.

Unlike the collages and films, Conner’s original drawings and inkblot works that don’t incorporate found items. These images, drawn in felt-pen, are almost maze-like, incredibly dense, intertwined and sedimentary. Unlike a maze, however, these terrains have no path and leave you searching for some point of reference. Additonally, the intricately folded inkblot pieces are minimal and spontaneous in their combination of ink and folded paper. Here one engages with the aesthetics more than any symbolic political meaning.

In the heavily textured assemblage piece Untitled (1960), the relationship of the work’s structural elements and its symbolic content proves more fruitful. The found items provide antecedents to their human histories making the viewer wonder where they come from, who they might have been used by. Similar to the assemblage works of his contemporary Robert Rauschenberg who also passed away this year, Untitled transforms the canvas space into a socio-geographic terrain adorned with all manner of found items. The central mass is comprised of heavy black mortar and imprinted with Inca iconography—a bird’s wing and Mexican beadwork cloth. The centerpiece, with a roughness to it reminiscent of melted and abstracted Incan art, sits in the middle of a bed of black fur and pearls, luxury items produced for post-industrial age of relentless consumption. The work’s center and surroundings parts are enclosed in an obscurant layer of taut black nylon; a representative consumer item to transcend luxury and working-class fashion into widespread and disposable consumption.

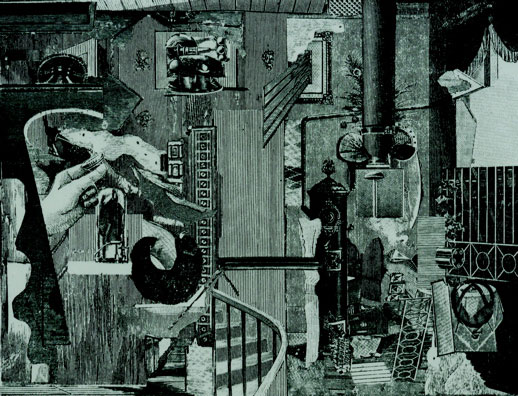

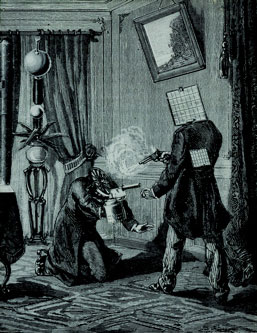

Conner made a number of works on display, such asDennis Hopper One Man Show and Criminal Act, made with the painstaking technique of photo-etching. These monochrome images abound with the hair-line finesse of detail like an etching but the intriguing aspect results from this technique applied to a photo-collage thus eliminating the usual distinct borders between constituent parts of the collage. Visual space overflows with minute detail and although the mind can distinguish various discordant images and figures, the overall visual plane appears smooth and harmonious. Some common motifs do present themselves in Conner’s work; feathers and fur, industrial antiquity, fake jewelry and nylon stockings, disembodied eyes and circular figures.

Miyake Fine Art’s exhibit allows the viewer to take in the movement, texture and atmosphere of Conner’s work through selection that creates a bricolage of his varied styles. Upon viewing, the styles and techniques of the works seem disjointed but in reflection this is something that an artist who never stayed confined to one genre or medium might have found appropriate.

Kenneth Masaki Shima

Kenneth Masaki Shima