Why Are Artists Poor?

When queried why he refuses to eat, Kafka’s hunger artist famously replied: “I cannot do otherwise.” The starving artist may be a cliché, but the hunger artist’s motivations remain enigmatic. In the world of contemporary art, the poverty of artists is equally misunderstood, though a recent book entitled “Why Are Artists Poor?” gives a fascinating account of its causes, and sets out possible remedies. Authored by Hans Abbing, a visual artist and professor of Art-Sociology at the University of Amsterdam, it offers a rigorous but highly-accessible argument about the economics of contemporary art.

“Why Are Artists Poor?” explores the panoply of truisms about the art market, the role of the state, the public, and the attitudes of artists themselves. Abbing proposes a multi-disciplinary approach, drawing on the insights of economics, sociology, and psychology. Briefly, he argues that art is shrouded in a pervasive mystique, but that the economy of art is also unique, resembling no other sector of production. The argument is based primarily on a study of the West (Europe, U.K., the Americas), though Abbing feels that his broader conclusions apply equally to the situation in Asia.

In fact, the poverty of artists is a recent phenomenon, with numbers increasing dramatically since WWII. A study of Holland indicates that the vast majority of artists (77%) are living at or below subsistence levels, and cannot make a living from art alone. A second job is necessary, and it typically generates twice the income of the art job. A graph of total income distribution of the artists in Abbing’s study resembles an asymptotic curve, with fewer than 1% at the top who are extraordinarily well off. Paradoxically, with the increase of prosperity in the industrialized nations, the number of impoverished artists has increased as well. Abbing argues that these developments are, in fact, connected.

In economic terms, this suggests an oversupply of artists, but unlike other sectors of the economy, artists do not quit. That they seemingly “cannot do otherwise”, leads Abbing to his first claim: the economy of the arts is exceptional. The usual mechanisms of supply and demand do not function. The question is: why not? Why do people become artists, knowing their compensation will be poor, and why don’t they quit when they have trouble surviving?

A dizzying number of reasons are interrogated and, unsurprisingly, money, fame, and recognition are not decisive factors. The most fundamental explanation for Abbing turns upon a sense that “art is special”, i.e., that to be involved in the art world with a capital-A is a special activity, that artists are driven not merely by their urge to create, but almost by a sense of social obligation. Since the nineteenth century, the practice of art has become a mode of authenticity. Many non-artists tend to see artists as somehow more authentic than themselves. This desire to give expression to an “authentic self” seems to be one of the main forces that attract young people into the arts.

Logically, one would expect that putting more money into the arts, either via state support or other forms of subsidy, would alleviate the poverty of artists. In fact, the opposite seems to be true: the number of poor artists actually increases. To understand why, Abbing distinguishes three groups: a small group who are not poor; second, poor artists, but seen from outside, seem that they “could have” avoided poverty; third, artists who are altogether poor, with the majority belonging to these latter two groups. The third is in the danger zone, but both second and third share a common work ethic: when money comes in, they invest it into their art, buying more equipment, putting more hours into their art job, etc. Their economic condition remains unchanged.

“Prosperity,” Abbing notes, “allows artists to be poor.” From this, he concludes that subsidies are counter-productive, induce market failures, and function as part of a vicious circle in the production of poverty.

This also raises a set of interesting questions about the relationship between art and the state. Is there a symbiotic relationship between them? Do governments support and serve art because it is important to society or, rather, because it serves certain government interests? For Abbing, states not only have interests, but tastes as well. He argues that modern states support the arts largely because of external pressure — what he calls “rent seeking” — from sections of the art world and various sectors of government, but that these subsidies may ultimately serve the interests of the state itself.

While Abbing draws sombre conclusions, his even-handed approach and prognosis for the future economy of the arts is ultimately refreshing. He finds recent evidence of a less “exceptional” economy, new attitudes among artists, and broader forces that are working to demystify the arts.

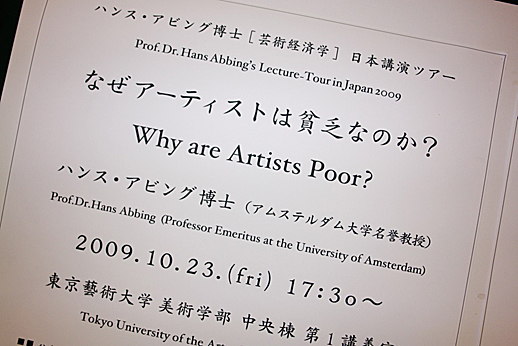

Hans Abbing will present “Why Are Artists Poor?” on November 1, at the Therme Gallery in Meguro. A lavish Japanese translation of Abbing’s book is available from grambooks.

Images used with permission of Takumi Suidu:

d.hatena.ne.jp

flickr.com

M. Downing Roberts

M. Downing Roberts