Tadao Ando, Least Modernist of Modernist Architects

These sections are quite functional since Ando started with houses and it is from there that his career unfolds. We see how his early ideas expand to a point toward the end of the exhibition where similar motifs are echoed his larger-scale civic projects. Each house is presented as a miniature case study, with a video detailing the final project, a review of its design elements, a 3-D model, and occasionally even correspondence between the architect and his clients. This last bit is a part of the design process you don’t often get to see, giving the overall sense that Ando’s creative process is really unique to each application.

This tailored approach may seem like an obvious statement about the design process, but with rock-star architects this history tends to get lost. Frank Lloyd Wright, for example, was notorious for his uncompromising designs to the point he would specify everything down to the furniture; Le Corbusier perhaps began the notion of the totalitarian architect. You rarely see the client interaction process with other architects of Ando’s stature. At this point, he could easily enforce his will on his projects, yet for him it truly is a continuing process of approaching each project as unique challenge, a case the organizers of this exhibition successfully make.

-模型.jpg)

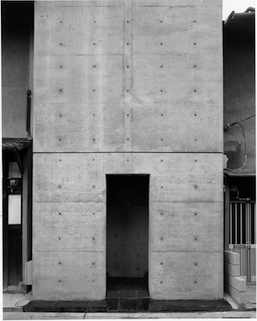

Ando fits in an interesting place in Japanese architecture. Kenzo Tange could be called the preeminent modernist, while surely Toyo Ito and Arata Isozaki are to be considered post-modernist. Then there’s Ando with his minimalism, exposed concrete, and lack of ornamentation, who is often viewed on the Tange end. However, Ando could also be viewed as the bridge, because while his style can be called modernist, he does not always fall in line with its overriding preoccupation of functionality. The act of having to use an umbrella on rainy days to go to the bathroom isn’t a Ludwig Mies van der Rohe attribute when discussing modernism. In correspondences there was a common sentiment that his clients had to learn to live in Ando homes, as most are cold during the winter, a complaint fashion designer Hiroko Koshino mentions for her home. Yet this is common of the greats – Wright’s John Wax Headquarters is notorious for leaks on rainy days. Pure functionality in the realm of livability isn’t a concern for many leading architects, but Ando takes it further. While aesthetically Ando may come off as modernist, the context in which he creates is anything but. It isn’t something as simple as insulation during winter, but the overall atmosphere that is brought into context.

The prevailing theme of “Endeavors” again is the process: The unique challenges that set up each building Ando creates. With his civic projects, one can appreciate how much he works with existing structures, drawing on his economical design. Afford yourself time to really read each case study, watch each video, and take in each model. Since it is fall and the sun sets earlier, to truly appreciate Church of Light, visit earlier to experience it in daytime and preferably on a sunny day. The exhibition catalogue is a thorough reference on Ando and makes for a bargain at only 1980 yen. The show isn’t exclusive for architectural fans, either, as there is something for everyone, especially in comparison to the “Tange on Tange” at Toto Gallery-Ma some years back. The Church of the Light replica simply needs to be experienced.