Monet’s Legacy

To create the desired mood for the show, a noren (a Japanese curtain-like divider) with Monet’s famous water lilies in a blue pond hangs near the entrance to the gallery hall. This exhibition is a contemporary Japanese view of Monet’s artwork and legacy, and summery images of bright flowers and cool water predominate. In fact, one of Monet’s less typical paintings of water lilies is spotlighted at the entrance. Although not one of his most famous, it is one of the gems of the show and in it you can see the painterly elements that will be extrapolated upon by others.

In the first section, “Towards a New Type of Painting,” several of Monet’s paintings from the 1860s to the 1880s are featured as works that defined Impressionism with their use of divisionism to capture the impression of the subject rather than its actuality. Monet’s work had painterly elements with their own value and meaning independent of the subject, and this interest in the act of painting itself and in the characteristics of the medium is shared by contemporary artists of many genres.

A variety of contemporary art sets the stage for the rest of the show: big names, local and international, and clever juxtapositions. Work by printmaker Katsutoshi Yuasa was obtained specially for the exhibition. His relief print Quadrichromie (2018) might either attract attention or be dismissed because it resembles a photograph, but a closer look reveals that Yuasa’s marks were all made in the same direction. Joan Mitchell, one of the comparatively few women artists in the show, is a legend herself, and her abstract oil paintings Purple Tree (1964) and Lake (1954) offer a rare chance to see her work outside of a book or website.

Willem de Kooning’s Water (1970) and Woman in Landscape (1966) repeat Monet’s motifs and continue the exploration of painting as a medium. The contemporary artist Kenjiro Okazaki uses prose as his titles, so his paintings are the only ones with any lengthy English explanation. Louis Cane’s paintings might shock traditional Monet fans with their explorative approach, but they serve both as a reminder that Monet was regarded as daring in his time. They are also as a sign of what viewers can expect in the other three sections.

The second section, “Looking at the Formless,” investigates shape-free motifs such as atmosphere, light, and water, as well as the abstraction of landscape and the visualization of movement and moments in time. With large color fields spread across Monet’s canvases, focal points and perspectives are lost or became minor. After a few difficult months after his wife Camille’s death, Monet began creating painting after painting of the ice breaking up on the Seine. Sunset on the Seine in Winter (1880) perhaps marks a change in Monet’s life. It is also notable for its landscape lit by a red sun instead of a white wintery scene.

Another series of Monet paintings featuring his impression of a sunset are the ones he painted in London of the Charing Cross Bridge. Monet was one of many French artists in self-imposed exile in England, escaping the turmoil of the Franco-Prussian war. This series of more than 35 paintings is also famous for recording the fog that London was famous for in the post-industrial era when the heavy pollution made the mist even thicker. Near this painting is also one of the sun setting on haystacks in rural France. The curators cleverly placed two large Rothkos near Monet’s sunsets. For viewers who could never understand or appreciate Rothko’s color field paintings, this placement would surely remind them of the horizon in Monet’s paintings. These conceptual paintings immediately become understandable to a general audience.

In the same room as all this color, the small black-and-white photographs of Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen seem to be hiding in the corner, although they deserve better. As an editor, gallerist, and artist, Stieglitz was involved in the modern art scene and closely followed the Impressionist movement in Europe. He used steam and fog to create photographic qualities similar to those of the Impressionists, and his photographs of clouds are regarded by many as some of the first abstract photos. Steichen also used light and mist to create the impression of emotions aroused by those scenes. He identified Monet as an influence, and later said that he was an Impressionist without knowing it. Stieglitz and Steichen were later the first to show Auguste Rodin, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, and Pablo Picasso in America.

Katsunori Mizuno’s video installations, reflection (2012) and photon (2018), create a soothing space to escape the outside heat. The videos have no obvious storyline and look like Mizuno’s impressions of a pond in a forest on a summer’s day. Another video in the third section, holography (2018), was created especially for this exhibition and the homage to Monet’s water lilies is obvious. It is approximately ten minutes long and the dark hall with seating where the other videos are viewed might have been a better location.

After a break in the cool darkness watching Mizuno’s videos, you are prepared to enter rooms with brighter, larger art. Monet’s Sun in the Fog (1904) is surrounded by larger color-field ones by Morris Louis and Yoko Matsumoto with two by works Gerhard Richter nearby. The comparison-contrast is striking. Suddenly Richter’s abstract paintings remind viewers of landscapes.

While many of the Japanese artists such as Reiji Hiramitsu and Miran Fukuda are quite literal in their tributes, Hisao Domoto is more subtle (aside from the title) with with Chain Reaction: for Claude Monet (2003). Many visitors will come to see famous paintings by Monet or Monet-like paintings, and the museum’s job was to do just that. The curators very cleverly mix artwork that is easy to understand at face value with more demanding abstract pieces.

“Beyond the Frame” is the finale of the show. The idea of extending the image beyond the frame is understandable, it but does not necessarily apply to most of the artwork in this section until you read the description for what the curators intended. The introduction mentions extreme close-ups of watery surfaces, water lilies and other floating objects; reflections, repeated motifs, and bold brushstrokes in Monet’s work translate to repetition, layering, and supposedly expansion into surrounding spaces in contemporary art. The entrance to this section is large and curving. Monet’s water lilies are on one side and Risaku Suzuki’s photographs and video of ponds with lily pads are on the other. To move them beyond the frame, a video screen is placed horizontally on the floor to resemble the pond in its video. As with Mizuno’s videos, Suzuki’s work provides a watery, cooling ambience instead of a narrative.

Two more Monet paintings are saved for the final room, and once again their juxtaposition with contemporary paintings is well-planned and eye-catching. The House among Roses (1925) shares a wall with Jean-Paul Riopelle’s Painting (1955), and everyone present commented on the clever pairing. Even young children can surely see the thick globs of red paint in the Riopelle and interpret them as the roses in Monet’s painting. Paintings by Sam Francis, Riopelle’s friend, hang nearby.

The final Monet painting, Weeping Willows (1897-98), is almost abstract in style. It is successfully paired with Landscape-Like Surface Vibrates III (1993) by Yoko Matsumoto. All of the women artists except for Joan Mitchell have paintings in the last room of the show. It is interesting to note that their work was used to create a great and final impression, but that the other rooms have work by mainly male artists. Miran Fukuda’s Water Lilies Pond, Morning (2018) is a contemporary take on reflections in a pond and references photography in her painting style. Yasue Kodama’s ‘Deep Rhyme’ series (2016) features paintings with variations on wintery trees. Together the works in the series could almost form a cell painting, yet they each retain their individuality.

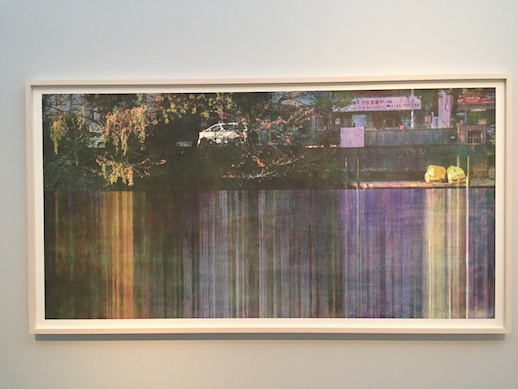

Andy Warhol’s Flowers (1970) is included to show another series artist, but does the work go beyond the frame? Probably not. On the other hand, Koseki Ono’s Namie (2017) seems to suggest the possibly of infinite size. Has it been laid horizontally on the floor specially for this show to suggest a lily pond? Maybe.

The curators also thought beyond the frame of the museum, setting a tiny lily pond outside for people to enjoy. It goes with the Japanese tradition of noting the seasons through flowers, colors, and decorations. Anything in shades of light blue is supposed to remind you of water and be psychologically cooling. That is why the museum staff created a pond outside and provided images of water inside. It is a summer show, complete with a light noren to blow in breezes from the air conditioning.

This ambitious exhibition succeeds in many ways, but not all. The use of colored walls is supposed to be for the Monet paintings, but that rule is quickly broken. Women artists are noticeably underrepresented but provide some of the best artwork in the show, regardless of nationality. Also, the catalog mentions that the work is divided into Japanese and foreign artists. Even if this is the case, is it necessary to mention it in the catalog? Another qualm is that all of the explanations are only in Japanese, despite the fact that the museum is a major tourist destination for people from all over the world, especially in summer. Even the exhibition hashtag is only in Japanese (#モネ2018). Issues like these are relatively easy to correct and would demonstrate that the Yokohama Museum of Art has the potential to be world-class.

A Century On: Responses to Monet’s Painting features art from the Yokohama Museum of Art collection and overlaps in dates with the main show. It focuses on the Japanese art resulting from exchanges between the East and the West, primarily in the Meiji era. Access is included with a ticket to “Monet’s Legacy.” яндекс

“Monet’s Legacy” is eligible for MuPon admission discounts.

Michelle Zacharias

Michelle Zacharias